TUNED IN

Sitting in a restaurant in Cincinnati last week, Jaime Jarrin shook his head and smiled.

“Increible,” Jarrin said.

He repeated the word several times over a lunch that lasted nearly three hours when describing his 50-year Hall of Fame career as the Spanish voice of the Dodgers.

He talked about how he came to the United States from Ecuador with $40 in his pocket on June 24, 1955, the anniversary of which will be celebrated this evening at Dodger Stadium before the Dodgers’ game against the Chicago White Sox. He talked about how he used to translate Vin Scully’s English-language broadcasts over the air from a studio in Pasadena. He talked about times he had to call games seated next to stadium loudspeakers or in places where his view of the field was obstructed.

For everything he endured, from his humble start in a factory on Alameda Street to surviving a nearly fatal car accident in spring training in 1990, Jarrin called himself fortunate.

He was fortunate to be at KWKW in 1958, when the station picked up the Spanish-language rights to the Dodgers and he was pushed by an ambitious station manager to learn a game about which he knew nothing. And he was fortunate to still be there in 1980, by which time he had worked alongside Rene Cardenas, Jose Garcia and Rodolfo Hoyos Jr.

That was when Fernando Valenzuela hit town.

“For me, Fernandomania didn’t start in ‘81,” Jarrin said. “For me, it started in ’80.”

Specifically, in the final series of the season against Houston. The Dodgers entered trailing the Astros by three games in the National League West. Valenzuela pitched a pair of scoreless innings out of the bullpen in both the first and third games of sweep, forcing a one-game playoff the Dodgers would lose.

By the next spring, the entire country was in a frenzy over the 20-year-old Mexican left-hander who looked into the heavens when winding up.

The club asked Jarrin to be Valenzuela’s interpreter.

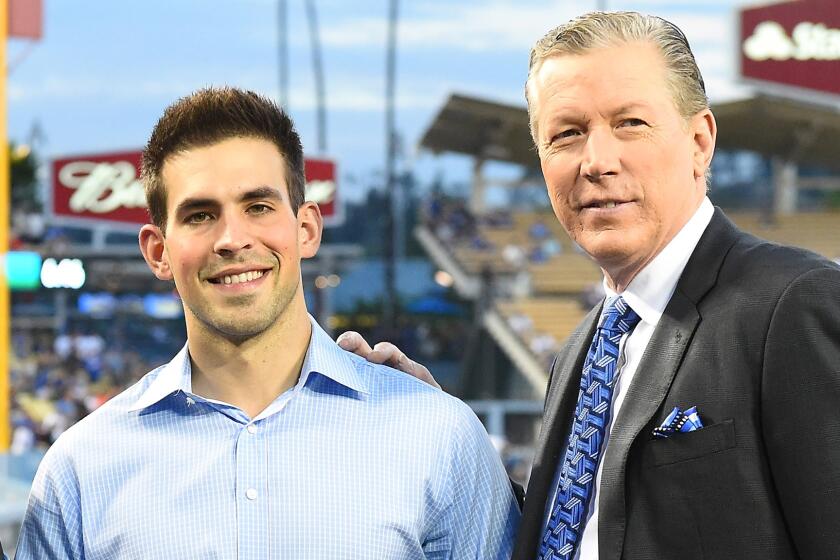

“We had to go to cities a day early for press conferences,” said Valenzuela, who works with Jarrin as an analyst. “Jaime was always there. He advised me on how to answer questions; he told me to think carefully before responding.”

Without any hesitation, Jarrin calls Valenzuela the player who had the single greatest impact on the Dodgers’ franchise.

“He created more new baseball fans than any other player,” Jarrin said of Valenzuela. “Fernando had that special talent, that special charisma to draw Mexicans, Central Americans and South Americans who were completely indifferent to the game.”

Jarrin’s listenership grew.

This wasn’t how Jarrin expected to leave his mark when he left Ecuador, where he was already an established newsman working for a 150,000-watt station that called itself “La voz de los Andes,” or “The voice of the Andes.” His sole purpose in leaving home, he said, was to “expand my horizons.”

With his future uncertain, his wife, Blanca, remained in Ecuador. He sold his pickup truck to a friend, only to learn that the friend never paid his wife. He had to send half of his $40 back to Ecuador.

He was initially rebuffed when approaching KWKW about employment, his inability to speak English and his age held against him. Jarrin, who landed his first radio job in Ecuador when he was 16 years old, was still only 21.

Over the first two decades of his U.S. radio career, his greatest on-the-air moments came outside baseball.

He won a Golden Mike in 1970 and again in ’71. He covered the slaying of journalist Ruben Salazar. He visited the White House twice on assignment. He was at Shea Stadium in 1979 for the visit of Pope John Paul II.

But there might not have been a place where the shift of the social landscape in this country was more visible than at post-Fernandomania Dodger Stadium.

“The team doesn’t win championships but draws 3.5 million fans a year,” Jarrin said. “One of my greatest satisfactions is that we might’ve been able to show other organizations the value of the Hispanic market.”

Latin players, once concentrated in a few markets, are everywhere. And Jarrin has helped usher in a new wave of Spanish-language reporters, among them broadcast partner Pepe Yniguez, who said he started listening to Jarrin when he was 16 years old and living in Tijuana. Yniguez said Jarrin inspired him to pursue a career in radio instead of print media.

“He is our Vin Scully,” Yniguez said.

Jarrin has a contract that runs through the 2011 season. His life, he said, is steady. He and Blanca live in the same San Marino home they bought in 1965 for $50,000. He hasn’t seriously pondered retirement.

“I was fortunate that a deep love for baseball awakened within me,” Jarrin said. “I love baseball. I could watch two games a day, seven days a week. I love it, I love it, I love it.”

--

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.