All’s Not Fair

It is a warm afternoon, a freezing afternoon, a spring wind blowing through the desert in daggers.

The Twentynine Palms High home opener is a day of baseball mismatches: shorts and mittens, hot dogs with hot chocolate, team caps on ski caps.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. March 24, 2003 For The Record

Los Angeles Times Monday March 24, 2003 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk 1 inches; 39 words Type of Material: Correction

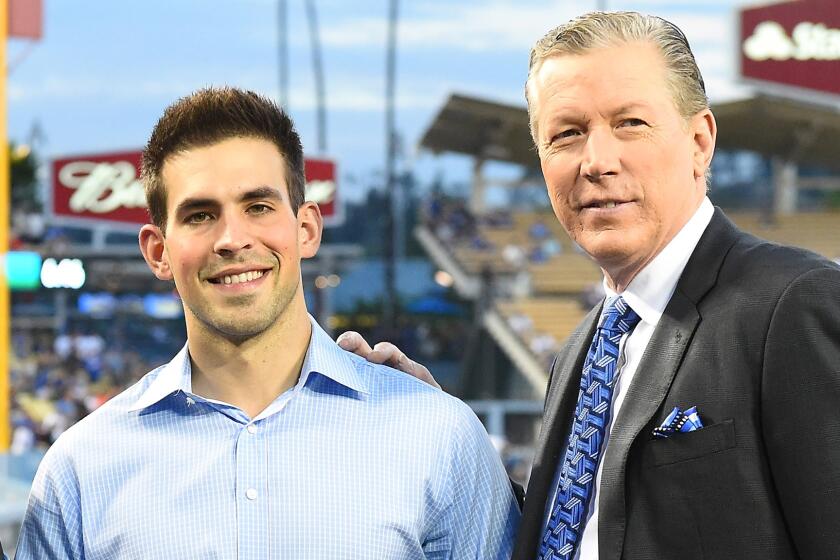

High school baseball -- A quote in a Sports photo caption that accompanied Bill Plaschke’s column on the Twentynine Palms High baseball team Sunday was incorrectly attributed to pitcher Eric Fernandez. The quote was from first baseman Jacob Lee.

Boys without fathers.

Eric Fernandez, the starting pitcher and Wildcat co-captain, peers into home plate for the sign that will not come.

The catcher is there, but Chief Warrant Officer Mark Fernandez is not, his usual seat behind the backstop empty while he marches toward Baghdad.

“Sometimes you get mad,” Eric said. “He was always my coach. He came to every game. He was always here.”

Jacob Lee, the first baseman and co-captain, kicks the gravel around first base while listening for a voice he will not hear.

Fans cheer, but Sgt. Major Charles Lee cannot, his familiar chirp engaged on the other side of the world, in a different sort of desert, coaching combat.

“You know how, even when everybody is shouting during the game, you could always hear your dad?” Lee said. “That was me and him. I always knew he was there.”

These days it is just the two of them, Lee and Fernandez, the leaders of a team that last year won two of 20 games, now forced to be leaders in homes broken by war.

They are only two, but they are hundreds, symbolic of the many children in this military town who have watched one or both parents disappear into the war with Iraq.

Some cope. Some do not. All are searching for something left behind, something to hold, something to help them understand.

Lee and Fernandez have found this anchor in father-son bonds nearly as old as war itself. It is the game their fathers taught them that will help them endure. It is baseball.

Said Lee: “I know it sounds corny, but it’s not. My dad taught me this game, and I’ll never forget him for that, and this is how I show it.”

Said Fernandez: “This was his game. This was our game.”

As part of a package sent to Charles Lee, his family threw in sunflower seeds.

It is hoped that chewing them in the desert will remind him of how he chewed them at Jacob’s games.

In a letter sent to Mark Fernandez, his family threw in photos of Eric in his baseball uniform.

This is one way, maybe the only way, that he can be convinced that everything back home is normal.

“Baseball is our way of letting Charles know that everything is all right,” said Patti Lee, Jacob’s mother.

Even when it’s not.

Soon, the fathers will be receiving news of that wind-swirled home opener.

One dad will hear how, alone at first base, Jacob Lee struggled to dig balls out of the gravel infield.

The other dad will hear how, alone on the mound, with the wind blowing in his face, Eric Fernandez was hit hard.

They will both probably hear how Twentynine Palms lost to San Bernardino Aquinas, 26-10, the Wildcats’ first defeat in three games.

What they might not hear is how their boys handled it.

Lee shouted at himself at first base but later told jokes as everyone eventually smiled through the hopelessness.

Fernandez trudged off the mound with his head down but later was stalking the dugout and leading the cheers.

Said Fernandez: “I found that to be quite surprising. Usually, I’m so hard on myself, it takes my dad to pull me back up. This time, I did it myself.”

Said Lee: “My dad would never let me quit. Well, I’m not quitting.”

It was a day of mismatches indeed, innocence shaded in wisdom, kids playing catch with a memory, prisoners who will not surrender.

*

While leading his team during a stretching drill recently, Jacob Lee was struck by a thought.

“Hey, everybody!” he shouted. “My father’s last letter was written on the back of an MRE [meals ready to eat] package!”

There was an awkward silence, as if teammates were expecting Lee to offer some uncomfortable introspection.

Instead, he smiled.

“You know what my dad wrote in the letter? Send more stationary!”

The players howled, the sound of relief, one of their leaders showing them again that wars don’t have to involve bunkers.

For the two Twentynine Palms captains, the team has become the refuge, their job has become the distraction.

“We have to lead our families, we have to lead our high school team, it’s sort of all come together at once,” Lee said. “It’s been hard, but you keep thinking that it’s going to make you stronger.”

Such strength is not so readily apparent in two so young.

Lee, 18, a senior, has shaggy hair and sprouting whiskers and granny glasses that cover playful eyes.

Fernandez, 16, a junior, is dark and serious with the smooth face of a child.

This being baseball, neither looks particularly like an athlete. Being only two of many military children in this desolate outpost, neither has felt like a hero.

They are the only two on the 14-player team whose fathers have been deployed. Yet they are the only two who never act as if it matters.

“We never talk about it; we kind of wait for them to say something,” teammate Charles Jones said. “But they never do. They’re too busy picking the rest of us up.”

Their fathers were bused away in late February, near the start of practice. Both men were rushed. Both exits were hurried.

“I hugged my dad late one night and the next morning he was gone,” Lee recalled. “It didn’t sink in until a couple of days later. I got home from school and the room was filled with his laughter and it got really hard.”

Both boys could have spent the rest of spring mourning and dreading. It happens all the time around here.

“When they started sending people out, a counselor from the base came out to school and talked to us about the ramifications,” said Stephen Ambuehl, the baseball coach who is also a teacher. “They told us to look for students shutting down, students acting distracted, kids moving out, and they’re right. I’ve seen all of that.”

Except on the baseball field, when Jacob and Eric decided that they would try to fix last year’s dreadful season instead of worrying about what CNN would be showing tomorrow.

So after one of the preseason practices, they helped organize a trip to McDonald’s that included the coach. Maybe not a big deal to your family, but a huge deal for their family.

Said Lee: “We had never done that before around. It was part of our coming together.”

Said Ambuehl: “I thought it was such a simple thing, but apparently the boys really needed it.”

When there were reports of players missing practice to hang out with their friends, the two boys arranged another preseason meeting, this time in front of the pitcher’s mound, players only.

“They asked if I could take a walk,” Ambuehl said. “I’ve been around a lot of high school baseball teams, but I’ve never seen this happen before. Of course, I took a walk.”

During the meeting, Lee and Fernandez stood up and scolded those who didn’t care as much as they did.

“We reminded everybody where priorities should be,” Lee said. “We told them, if that’s the way you want to play ball, you’re not playing on this team.”

Watching the meeting from the outfield, Ambuehl couldn’t believe how two kids could simply step in and take over a team that once had chemistry like a ninth-grader’s sulfur experiment.

“I was a little afraid that this team would have leadership issues,” said Ambuehl, a 27-year-old in his first full year as their boss. “I realized then that we wouldn’t.”

After their first two games, it was apparent that maybe they wouldn’t also have losing issues.

They beat Desert Christian twice by a combined score of 40-4. Fernandez had a win. Lee had four hits in six at-bats.

In a blink, they had already recorded as many wins as in all of last season. Then they showed up for their wind-swept home opener and were blown away by Aquinas. But it’s a start.

“And it’s three hours a day that Jacob doesn’t have to think about anything else,” Patti said. “That makes baseball important right there.”

If only the rest of their days were so easy.

Lee’s father has always called him “Baby Boy,” but after this year, that will have to change.

Those nights when he used to lie on the couch and toss the baseball up and down, they are now spent making sure his mother’s car is running and the TV and stereo are working and everything else is just right.

“I think he feels like he needs to take care of me,” said Patti, a Marine wife of nearly 30 years. “That’s the first time he’s been like that.”

Fernandez’s father has always called him “Mi Hijo,” which is Spanish for “my son.” By the time he returns, he may want to refer to him as more of an equal. Eric has been doing everything from caring for his two younger sisters to investigating strange noises outside the house in the middle of the night.

“Eric is tackling things,” said his mother, Yvonn. “He has shown he is not afraid to step up to the plate.”

Even when there is nobody sitting behind that plate.

Fernandez sighed.

“It makes me mad that my father is gone,” he said. “But I know he will come home. He has to tell me to keep my back straight. He has to remind me to keep my pitches down.”

Lee shrugged.

“Sure, I’ve thought about the what-ifs; it’s always in the back of my mind,” he said. “But then he sends me a letter. Asking me about my baseball.”

*

Bill Plaschke can be reached at bill.plaschke@latimes.com.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.