Teammates recall how Shaq mastered the game in his youth

The first day Stephen Roberts met the teenage Shaquille O’Neal, O’Neal was a newcomer to Ft. Sam Houston.

“He was wearing a clock,” Roberts recalls.

He wore the clock on his first day of school at Robert G. Cole High in San Antonio, too, as Darren Mathey recalls. It was an homage to the rapper Flavor Flav and coupled with a Gucci ski hat sitting high on his head.

And when he walked into the geometry class taught by basketball coach Dave Madura, a staffer presented him as a surprise for the coach. As the new kid appeared, Doug Sandburg’s eyes widened at this thought: “Holy cow, we’re going to be good.”

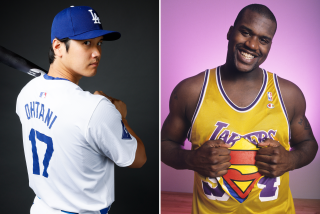

Cole went 68-1 in two years and won a state championship in 1989, thanks in part to this giant with a personality befitting that outsized clock he often wore. But no one on that team could have known back then that 10 years later he’d turn into the NBA’s most dominant big man. They didn’t know that 20 years later he’d have won four NBA championships, three with the Lakers. They couldn’t fathom that nearly 30 years later he’d stand on a stage in Springfield, Mass., accepting his induction into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame, and that when he did it he’d talk about all of them.

“It was [in San Antonio] where I realized the cliche is true: there is no I in team,” O’Neal said Friday night. “I couldn’t have done it without Doug and Dan Sandburg, Joe Cavallero, Darren Mathey, Rob Dunn, Eric Baker, Dwayne Cyrus just to name a few.”

His old teammates and coaches all watched with pride, some in Springfield at O’Neal’s invitation, some from their homes in central Texas. They had grown up watching the gestation of a Hall of Fame career.

“He was authentic to himself and that’s all anyone can ask of someone,” Doug Sandburg said. “It’s just nice to say that we could have been part of his life and helped mold someone that is that awesome.”

He entered their lives when his stepfather Phillip Harrison, an Army reserve sergeant, was transferred to Ft. Sam Houston in 1987. (A rumor persists in those parts that upon hearing about Harrison’s son, the post commander ensured his transfer.)

He learned how to use his size, rather than the agility he preferred showing off.

“His dream, honestly, was to be a point guard,” said Mathey, the actual starting point guard on their state championship team.

He added strength to his gangly, sometimes awkward frame. He and assistant coach Herb More would face off in three-point shooting contests after practice, sometimes for hours. In practice, More was often tasked with pushing O’Neal in scrimmages — a rare figure big enough to match him.

As his legend spread, the attention grew. The junior varsity team played to standing-room-only crowds because if you didn’t get in for the undercard, you’d never get in for the main event.

Another high school team was scheduled to play near a Cole road game once, but plans changed when their coach realized O’Neal was nearby.

“He ended up canceling the game so he could bring his team to watch us play,” More said.

And everyone wanted a piece of him in pickup games. The players from bigger schools who never got to face him in organized games. The soldiers on post who wanted to test themselves against this alleged phenom. They’d arrive at a local gym or a playground called the Red Hut wanting to play.

Those who made the mistake of trash-talking O’Neal, or questioning his prowess, paid for it. O’Neal’s ferocity kicked in and a show at their expense followed.

Other times, the goofball emerged.

“When it was against his friends it was don’t-even-tie-your-shoes Shaquille,” Roberts said. “When he would play with his friends, he would be a point guard. He would dribble down the court and do all these moves. He’d be making this swooshing noise, shhh, shhh, shhh, almost like he’s that fast, but he’s not. He’d just be making that noise. He’d pull up for threes. He was playing with friends. He was having a good time.”

They’d play at the Red Hut until the lights came on, then someone’s mom would call them back home and they’d go to someone’s house for dinner.

That O’Neal is who his high school teammates remember most fondly.

When they watched his Hall of Fame acceptance speech, that’s the Shaq they saw. They laughed at his dead-on impersonation of their beloved and profane high school coaches (most of which was censored heavily on television). They watched him thank all the people who helped build his career.

They got to feel part of it, and all the memories raced back.

tania.ganguli@latimes.com

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.