Albert Pujols’ return to St. Louis set for adulation, not condemnation

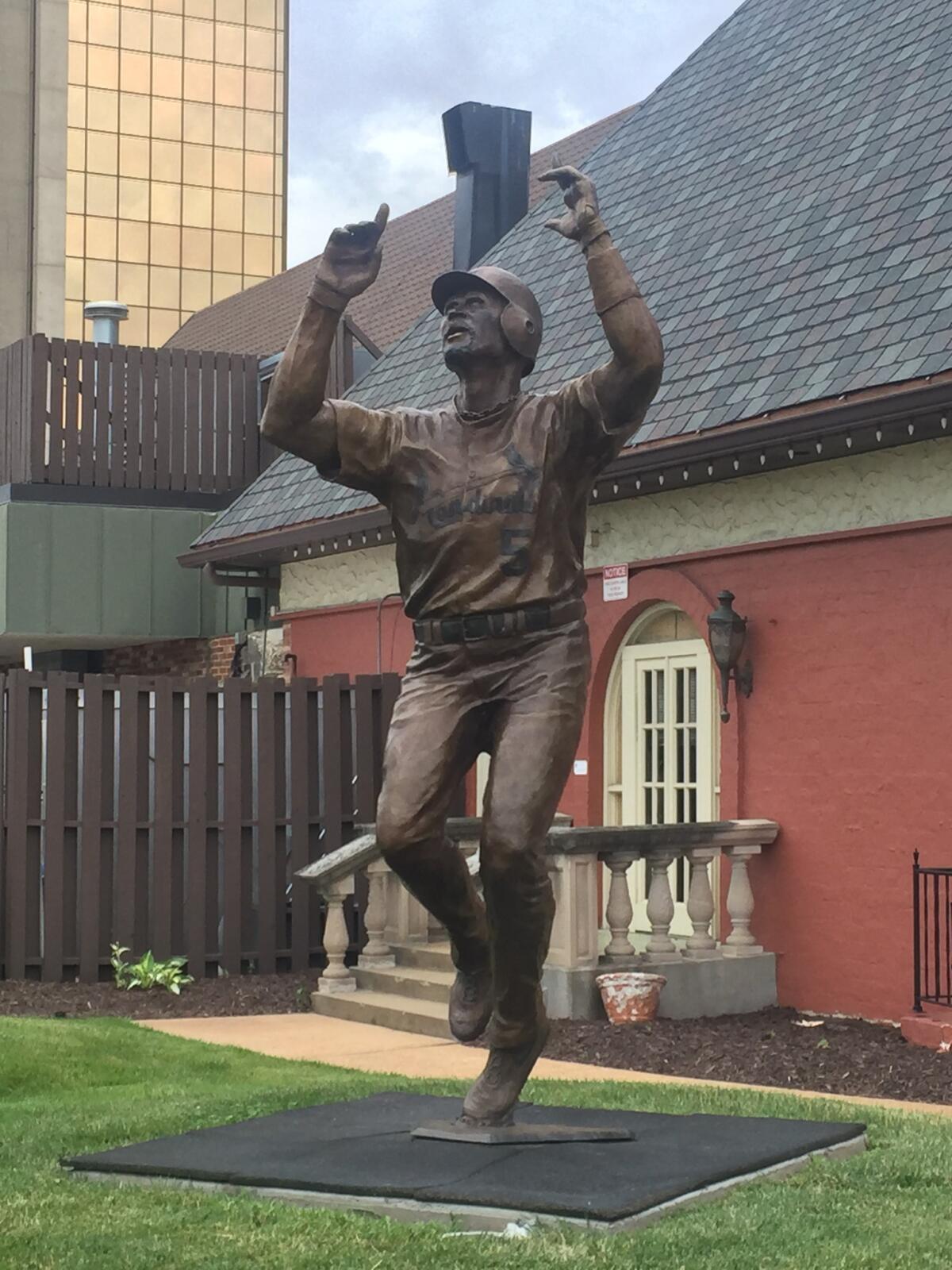

The bronze of the statue glints atop a berm near the parking lot of a Sheraton hotel, in a shopping plaza about 18 miles west of Busch Stadium. The sculpture rises 10 feet high, weighs 1,100 pounds and recalls an enduring image of another era: Pointing skyward, posing for posterity, swaddled in the No. 5 jersey of the St. Louis Cardinals is Albert Pujols.

It was a gift, commissioned by an anonymous donor to Pujols’ foundation, crafted by the same sculptor who built the statues of Stan Musial and other Cardinals that guard the gates of the ballpark. The re-creation of Pujols was unveiled in November 2011, a few days after he played his final game as a Cardinal and a month before he signed a decade-long contract with the Angels, near the entrance of a restaurant that bore his name. The name changed when he left. The place closed a couple years ago.

Inside the plaza, Pujols maintains the headquarters for his foundation. He still does charity work here, nearly a decade after departing. But he has yet to return in uniform as a visiting player at Busch Stadium, where he celebrated two World Series titles and built a legend. That changes when the Angels come to town Friday. The impending reunion left the 39-year-old feeling wistful.

“St. Louis is always going to be home for me,” Pujols said. “No matter where I play. It doesn’t matter what uniform I wear, or where my work is. It still has a special place in my heart. It’s something you cannot ignore.”

The adulation of a Midwestern sports monolith await Pujols. The fans of the Cardinals saw Pujols surmount the sport for 11 seasons. Before his future teammate Mike Trout claimed the throne, the sobriquet of “best player in baseball” belonged to Pujols. He won three National League MVP awards and finished in the top five on 10 occasions. “Those 11 years,” former Cardinals manager Tony La Russa said, “were magical.”

As an Angel, his production has plummeted. His body has betrayed him. He has celebrated his 3,000th hit and his 500th and 600th home runs far from the fans who once adored him. The schedule provides an opportunity for Pujols to reconvene with them.

The acrimony that surrounded his exit has faded, suggested teammates, coaches and executives who watched Pujols in St. Louis. All that remains is affection for a player in the twilight of a Hall of Fame career. Cardinals general manager John Mozeliak suggested the initial ovation for Pujols could last three minutes. David Freese, the Dodgers first baseman who starred in the 2011 World Series with St. Louis, had a better idea.

“If he leads off an inning for that first at-bat,” Freese said, “the defense shouldn’t even go out on the field for like five minutes.”

::

One morning in the spring of 2001, inside the weight room of the Cardinals’ complex in Jupiter, Fla., catcher Mike Matheny was consoling Pujols. Your time will come, Matheny explained. Go to triple A and get ready. As Matheny offered wisdom, La Russa called Pujols into his office. A demotion looked inevitable.

Pujols was only 21. He had terrorized opposing pitchers that spring, but the Cardinals prized experience and Pujols had none. He was not far removed from a boyhood in the Dominican Republic and an adolescence split between New York and Kansas City. He had played only three games above Class-A. St. Louis planned to season him in the minors, but six weeks in the Grapefruit League changed their mind.

Matheny was lifting weights when Pujols burst back into the room. He beamed when he told Matheny he would travel north with the team. The veteran congratulated the rookie and returned to his workout. Only in retrospect, Matheny mused, did the conversation become significant.

“Little did we know,” Matheny said, “we were watching the beginning of one of the greatest runs in baseball history.”

Pujols arrived as if fully formed. He was studious, pious, respectful. He understood his place in a clubhouse populated with veterans such as Matheny, Mark McGwire and Jim Edmonds. His talent was irrepressible. He hit .329, made the All-Star team and won rookie of the year. “Right from the get-go,” said former first base coach Dave McKay, “he showed you he could hit off anybody.”

And then he got better. Pujols hit .359 and won the batting title in 2003. He won his first MVP award in 2005. In 2006, a season in which the Cardinals sneaked into October and streaked to a title, Pujols led the National League with a 1.102 on-base-plus-slugging percentage. Two more MVPs followed in 2008 and 2009. He insisted to La Russa each spring that he would improve, and he unleashed that fury on opponents. “His mind-set was, ‘Who am I going to make pay today?’” Matheny said.

The franchise molded itself around Pujols. Teammates flocked for advice. The coaches deputized him to motivate the clubhouse. “Let me know if I’m not running hard enough,” Pujols told McKay. He held peers to the same standard. He mentored a young catcher, Yadier Molina. “He was the epitome of a coach in the locker room,” said former Cardinals assistant hitting coach Mike Aldrete.

The city debated his nickname. If Stan Musial was The Man, then Pujols would be El Hombre — except Pujols rejected this, out of respect for Musial. La Russa called him “Albert P. Pujols.” The middle initial stood for “Perfect.”

“You can’t make a player, or person, better than Albert,” La Russa said.

His dedication extended away from the park. In 2005, Pujols and his wife, Deirdre, launched the Pujols Family Foundation. Their daughter Isabella was born with Down syndrome. The foundation raises awareness for the condition. Pujols filled his calendar with events during the summer, even when his body demanded rest.

Todd Perry, executive director of the foundation, described Pujols’ devotion as “absolutely astounding.” He recalled Pujols fouling a ball off his foot during a game and attending an event that night. “He couldn’t even walk,” Perry said. “He actually came to a bowling event and had to sit down. But he came.”

The workload did not hamper his routine at the ballpark. Freese recalled Pujols as a metronome; the same activities, day after day. Even the coaches marveled at his dual dedication to the community and the club. “I sometimes couldn’t fathom how you could do all those things,” Aldrete said.

Pujols was not perfect. He could be gruff with reporters. He caused a brief stir during the 2011 World Series when he didn’t speak with the media after Game 2. The tempest disappeared by Game 3, when Pujols became the third player in the sport’s history to homer three times in a Fall Classic game. Five days later, he scored on Freese’s season-saving triple in Game 6. St. Louis secured the title the next night.

Pujols dropped to a knee at first base as the final out was recorded. His 11 years in St. Louis were remarkable for their consistency and their ferocity: Pujols averaged 40 homers and 121 RBIs, with a 1.037 OPS. He was 31, and on the verge of free agency.

Never again would he wear a Cardinals uniform.

::

The call reached Mozeliak, the Cardinals general manager, in the morning of Dec. 8, 2011.

On the other end of the phone was Dan Lozano, Pujols’ representative. For two years, St. Louis had tried to forge a long-term extension with Pujols. Lozano let Mozeliak know that the chase was over. After two feverish days of negotiations at the winter meetings in Dallas, Pujols had agreed to a 10-year, $254-million deal offered by Angels owner Arte Moreno.

Mozeliak hung up the phone. He informed his deputies. The group caught a ride to the airport and flew back to St. Louis.

“There’s a feeling of rejection, and having to accept that you weren’t chosen,” Mozeliak said.

The Cardinals had ushered in an offseason of transition. La Russa, McKay and pitching coach Dave Duncan retired. Matheny had been hired as manager in November; he got the word while on a charity trip to the Dominican Republic with Pujols. Unable to share the news with the free agent, Matheny could not dissuade Pujols from catching a flight to hear a pitch from the Miami Marlins.

Pujols saw through Miami’s bluster. But a more serious suitor emerged when the industry gathered for the winter meetings. Jerry Dipoto, then the Angels general manager, contacted Lozano that Tuesday. Moreno and his wife, Carole, spoke on a conference call with Pujols and Deidre soon after. Pujols made his decision Thursday morning. He was introduced, along with fellow free-agent acquisition C.J. Wilson, on Saturday at Angel Stadium.

“I think Arte was able to touch a part of Albert’s heart,” Lozano told The Times in 2011. “He made him feel wanted, that this wasn’t just a business decision, that it was something very personal for Albert.”

Implicit in the praise of Moreno was the contrast with the Cardinals. The final offer from St. Louis has been reported as a 10-year, $210-million contract with $30 million deferred. The Angels required no deferred money, and included a 10-year, post-retirement personal services contract. St. Louis did not have a similar package in their offer; the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported earlier this year that the team believed that was implied when they asked Pujols to be “a Cardinal for life.”

The disconnect created an opening. Pujols insisted his decision was not based on money; he has said that because of California taxes, he makes less than he would have in Missouri. Deidre Pujols told a St. Louis radio station in 2011 about the confusion created when a five-year, $130-million offer was on the table.

“They made one offer that was basically disrespectful to him,” La Russa said. “And that sent the wrong message. I also know that they had some financial limits that other teams don’t have, so they couldn’t go crazy for him. But based on everything there, I wish they could have stretched some more. Him being in uniform in that place would have been special.”

Mozeliak does not enjoy recounting the talks with Pujols. He felt a kinship toward the player; he had often consulted him on how to improve the club. He described the negotiations as “a very emotional and stressful time, for everybody involved.” He found himself weighing the present-day value of Pujols, the cornerstone of a championship club, and the long-range consequences of a nine-figure financial commitment.

“It’s hard to try to get away from the moment,” Mozeliak said. “Any time you sign a player, there’s this euphoria, like ‘Yes!’ Everybody gives you credit and says great things. But that’s not when you judge a deal. Deals are judged over time. And unfortunately, that was the process we were trying to deal with.”

The actuarial tables suggest all players, even generational stars, decline as they age into their 30s. Pujols did. Mozeliak was not wrong. And the Cardinals did not capsize without Pujols. Under Matheny, the team made the postseason four years in a row. St. Louis reached the World Series in 2013, but has not secured a championship since Pujols left. Neither has Pujols.

“You can argue maybe the perfect ending would have been like Stan Musial, start to finish with one organization,” Mozeliak said. “But in this day and age, that’s very difficult to do. When people ask me, ‘Well, how do you feel about Albert Pujols?’ I feel grateful that we had him when we had him.”

::

In the summer of 2013, Pujols went to lunch with McKay. Retirement had not suited McKay, so he joined the Chicago Cubs as a coach. He dined with his former player before an interleague series in Anaheim. Pujols was disappointed in his hitting, which would result in a career-low .767 OPS, and troubled by plantar fasciitis in his foot.

McKay reminded Pujols that he had been the best player in the world for 10 years. It would be impossible, McKay explained, to maintain that level. He suggested Pujols rest his legs.

“They pay me to play,” Pujols told McKay.

Sign up for our daily sports newsletter »

The doggedness that defined him as a Cardinal could carry him only so far as an Angel. Pujols underwent season-ending surgery that August. He stayed productive through the first five seasons in Anaheim: 29 home runs per season, 98 RBIs and a .799 OPS. The Angels won 98 games and the American League West by 10 games in 2014, but got swept in the first round. Pujols has not won a postseason game since Game 7 in 2011.

His decline, of course, was inevitable. Aldrete, now a coach with the Oakland Athletics, still sees Pujols often. The presence of his former player in the batter’s box still registers.

“He’s not the Albert that I saw in ’08 and ’09,” Aldrete said. “But for sure, it’s amazing what he’s doing right now. His body is not the same. I mean, how many of us are at age 40 what we are at age 26?”

Pujols continues to push forward. His foundation has expanded its efforts; Perry, the executive director, indicated they are running 40% more events in St. Louis in 2019 than they did in 2011. Pujols still attends in the offseason — even when his body does not want to cooperate.

After foot surgery in December 2016, Perry recalled, Pujols was considered unlikely to attend a foundation function in St. Louis. He boarded a flight anyway. “I’ve got to be here,” Pujols told Perry. After he underwent knee surgery in 2018, Pujols traveled with Perry to Nashville. On the ride to the venue, Perry sensed Pujols’ discomfort.

“He was sitting there grunting in pain,” Perry said. “And we get to the event, and he stands up and takes pictures with everybody. But if you know Albert, it’s almost as if you would expect nothing less.”

Added Perry, “He doesn’t have a low gear. It’s full bore or nothing.”

Perry did not plan to burden Pujols with events this weekend. But the foundation plans to buy a section of tickets for Sunday’s series finale. Pujols indicated he also would have a few suites for the weekend, a venue for family and friends to gather for the reunion.

Pujols said he did not have expectations for the reception. He hoped it would be positive. He understood how the embrace of his former home felt.

“St. Louis is just the best city to play baseball, the best city to play sports,” Pujols said. “They are loyal to their players. It’s a really special place to play, and I’m blessed to have the opportunity to play there for 11 years, and have the success that I had, too.”

Twitter: @McCulloughTimes

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.