Why Dallas Keuchel, Craig Kimbrel should sign deals after MLB draft

One of baseball’s most reliable proverbs is this: You can never have too much pitching. This winter provided an addendum to that axiom: You can never have too much pitching — unless it costs too much money.

All 30 Major League Baseball teams could use a reliever like Craig Kimbrel. Since he debuted in 2010, he has made seven All-Star teams, led his league in saves four times and never played a season with a strikeout rate lower than 36%. The sport prizes pitchers who miss bats. Few are better than Kimbrel.

All 30 teams could use a starter like Dallas Keuchel. He won the American League Cy Young award in 2015 and owns four Gold Gloves. He has never given up more than 20 home runs in a season. The sport rewards pitchers who get outs on the ground and keep hitters in the ballpark. Few are better than Keuchel.

All 30 teams have known these facts about these two pitchers for months, long before they became free agents last November. Yet none of the 30 teams employs either man. That is likely to change, perhaps as early as Monday, but the unemployment of the duo still acts as one last reminder of this winter’s enmity between the players and owners.

The reasons espoused by teams may be sound. They might feel Keuchel and Kimbrel demanded too much money. They might be wary of losing a draft pick. They might be fearful of getting taxed. They might feel more comfortable using internal depth to plug roster leaks. The reasons may be sound, but they do not matter: Neither Keuchel nor Kimbrel has a job, and that serves as a blight on the sport.

The Major League Baseball draft will begin Monday, which will remove the yoke of draft-pick compensation that reduced interest in Keuchel and Kimbrel, both of whom rejected one-year, $17.9-million qualifying offers at the start of the offseason. By Monday, the market for both pitchers is expected to be robust, according to executives. The New York Yankees could be a fit for Keuchel, while the Minnesota Twins make sense for Kimbrel. The Atlanta Braves might pursue both.

Both men will get paid, and the sport will roll forward. Two months of the season are complete. Keuchel and Kimbrel will be welcomed in their clubhouses, and the victorious front offices will be heralded for their business savvy. But the seeds of discontent sown over the offseason will continue to grow roots.

The sparring between the labor force and teams quieted in March, when Manny Machado signed a $300- million deal with the San Diego Padres and Bryce Harper found a $330-million contract with the Philadelphia Phillies.

Soon after, Nolan Arenado’s $260-million extension with the Colorado Rockies and Mike Trout’s $430-million extension with the Angels ignited a trend throughout the industry in which Chris Sale ($145 million), Paul Goldschmidt ($130 million) and Jacob deGrom ($137.5 million) all got paid.

The outpouring of cash was an encouraging sign for those interested in labor peace. Even so, it did not solve the dilemma that prevented Keuchel and Kimbrel from finding suitable offers before June: The collectively bargained compensation system rewards players when they reach their 30s, and teams have determined those players are no longer worth rewarding — at least at the rates to which they have grown accustomed.

Both Kimbrel and Keuchel are 31. Kimbrel was believed to be seeking a six-year, $120-million contract at the start of the winter, which would have well exceeded Aroldis Chapman’s five-year, $86-million deal with the Yankees, which was the most lucrative deal ever for a closer. Keuchel was worth $26.4 million in surplus value last year, according to FanGraphs, and was believed to be interested in a deal with an average salary in that ballpark.

Those requests are reasonable in a world in which baseball teams pay the players based on precedent and reward past success. For a few decades, as baseball emerged from the era of collusion, that world existed. Players were willing to receive lesser compensation in their early years in exchange for the theoretical panacea of free agency.

The world started to change after the winter of 2015, in which disastrous contracts were given to Chicago Cubs outfielder Jason Heyward ($184 million), Baltimore Orioles first baseman Chris Davis ($161 million) and Detroit Tigers pitcher Jordan Zimmermann ($110 million).

The inefficiency of those nine-figure contracts hasn’t changed. Harper entered Friday with a .252 batting average. Machado had a .783 on-base-plus-slugging percentage. And long-term deals for position players are considered less volatile than deals for pitchers.

The collective bargaining agreement struck in 2016 did the players few favors. The free-agent market suffered from two provisions: one forcing draft-pick compensation to sign certain players and the other reinforcing a luxury tax that serves as a soft cap on spending. It is not difficult for a team to explain why it avoids a nine-figure commitment to a player.

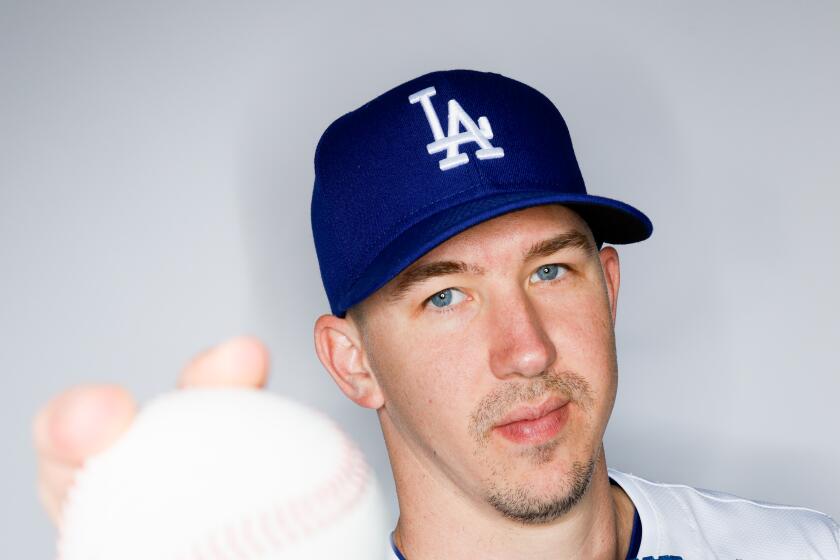

Take the Dodgers. They are one of the 30 teams, and so they could use either Kimbrel or Keuchel. The starting rotation entered the weekend with the lowest collective ERA in the National League. But the bullpen has been unreliable, with few trustworthy options outside of Kenley Jansen and Pedro Baez.

The addition of Kimbrel would provide an obvious boost. If the Dodgers signed Keuchel, they could shift Kenta Maeda into the relief role he has helmed during the past two postseasons. Both players would make the team better.

Sign up for our daily sports newsletter »

There are a few caveats: Kimbrel is believed to prefer pitching the ninth inning, which could lead to conflict with Jansen. And Maeda’s contract is heavily incentivized toward starting, which could lead to discord. The Dodgers are unlikely to acquire Keuchel or Kimbrel. But either player would would improve the team’s chances of ending a 31-year championship drought. That either pitcher could help the Angels is self-evident.

In this era, teams no longer value the immediate satisfaction of aiding their team in the present. The Dodgers are wary of violating the luxury-tax threshold, and their recent free-agent purchases have gone poorly. Outfielder A.J. Pollock slumped through April and may not return from a staph injection until July. Reliever Joe Kelly had posted an 8.35 ERA heading into Friday.

There are reasons. And there were reasons for every other team to stay away. On Monday, that is likely to change. But the long-term problems will still remain.

Twitter: @McCulloughTimes

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.