How baby boomer managers reach these dang millennial players

L.A. Times Today airs Monday through Friday at 7 p.m. and 10 p.m. on Spectrum News 1.

Ron Washington signed his first baseball contract in 1970. He played his final game in the major leagues in 1989. He became a coach in the 1990s. The Texas Rangers hired him to manage their team in 2006. He persists in this, his fifth decade in the sport, as a coach for the Atlanta Braves and a sage noted for connecting with players.

Earlier this year, Washington turned 67. He is a baby boomer surrounded at the ballpark each day by millennials. He traverses the generational gap by seeking to impart wisdom and unlock the potential of his pupils.

“Today, they don’t know what work ethic is,” Washington said. “They don’t know what consistency means. And consistency means you’ve got to go on the field and work at your craft. We worked at our craft consistently back in those days.”

The rhetoric espoused by Washington has been echoed, perhaps in varied tones, throughout the industry. During this decade, the landscape of advanced metrics has flattened; all 30 teams employ analytics departments. The latest advancements focus on player development rather than talent procurement. The best organizations strive to optimize their players. To do so requires communication above all.

So as baseball wades deeper into its information age — a time of Rapsodo and TrackMan, launch angles and spin rates, pitch tunneling and catch probability — managers, coaches and executives are confronting a comprehensive challenge: how to talk to these dang millennials.

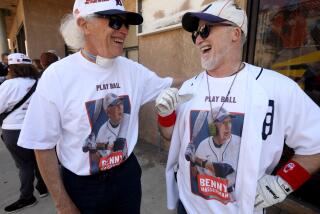

“You really can’t make a lot of these guys do anything,” said Dave McKay, the 69-year-old first-base coach for the Arizona Diamondbacks. “You have to find a way to convince them to play hard for you.”

Washington and McKay may sound anachronistic. But they remain employed because of their affability and open-mindedness. They present themselves as allies to the players rather than pedagogues. Washington spoke without rancor or bitterness. He did not rage about sabermetrics or iPhones. He insisted he does not blame younger players for their attitudes. They know no better, he explained.

“That’s just the generation they’ve come up in,” Washington said. “They’ve been coddled. They’ve been always directed. They’ve always been told to go over here to the right ... and then take two steps to the left. They don’t get a chance to figure that out for themselves.”

The average age of a major leaguer in 1999 was 28, according to Baseball Reference. In 2009 it was 28. The number remains 28 in 2019. But this crop of 28-year-olds came of age during an era of text messages, YouTube and an education system built around standardized testing, a millennial generation defined as those born between 1981 and 2000 by the Pew Research Center.

The difference between the generations can be stark, indicated Ned Yost, the 64-year-old manager of the Kansas City Royals. Take the cinematic cliche of a skipper berating his team.

“The manager would come in, scream at you, and it was like water off a duck’s back: Who cares?” Yost said. “Now you scream at them, they’re butt-hurt for two weeks.”

Gabrielle Bosche runs a consulting company called the Millennial Solution, which demystifies their behavior in professional settings. In an interview with The Times, she outlined “the three core tenets of millennial motivation”: setting expectations, providing explanations during instruction, and connecting tasks to a larger goal.

Those tenets were often repeated, unprompted, by baseball officials during interviews about the modern player. Teams text players the next day’s lineup the night before a game. This season the Chicago Cubs have issued the lineups before every series so the players can plan their week.

Dodgers manager Dave Roberts canvasses his clubhouse hoping to speak with each player on a daily basis. This task arises in part from his upbeat disposition. But he also considers the consistency vital.

“If there’s not constant communication, then there’s a lot of ‘I was told this,’ ” Roberts said. “For me, millennials, being flexible, it seems harder.”

Roberts was born in 1972, a member of Generation X. His father was a Marine. Roberts considered instruction from superiors to be sacrosanct. When a coach directed him to perform a task, Roberts said, he rarely asked questions.

The current crop of players react more casually to authority, Bosche explained.

“Keep in mind: Millennials were parented in a very democratic way,” Bosche said. “Parents were like, ‘Where do you want to go on vacation?’ And my parents’ generation got in the back of a station wagon and went where dad wanted, and watched whatever dad watched. So our relationship to superiors is much more relaxed than past generations.”

Earlier this decade, coaches absorbed information from the front office and distilled it to the players. As the numbers became publicly available, the players began to concoct ideas of their own. Some grew up taking batting practice with swing sensors and studying data about their release point after bullpen sessions.

The two-way flow rewards coaches who engage in dialogue. That skill is what appealed to the Dodgers about Dino Ebel, 53, who was hired to coach third base this offseason after more than a decade coaching with the Angels.

“I have the information, and while you’re talking to them, in the conversation, you include the data, what we’re doing,” Ebel said. “You make it into a conversation. You hear what he has to say. What I found out is if you let them talk, then it works.”

The Dodgers added a millennial to their staff this winter when they brought on 36-year-old former catcher Chris Gimenez as a game-planning coach. Throughout the industry, teams have begun to surround youth with relative youth.

After a losing campaign in 2018, the Minnesota Twins deposed manager Paul Molitor, a 62-year-old Hall of Famer. In his place, chief baseball officer Derek Falvey (36) hired Rocco Baldelli (37). The coaching staff surrounding Baldelli also reflected the shift.

When searching for a pitching coach, Falvey opted for Wes Johnson, who had been at the University of Arkansas. Johnson offered a dearth of big league experience. He had never played professional baseball or coached at the professional level. But he had studied biomechanics while coaching at Central Arkansas, and learned how to use the pitch-tracking device TrackMan with Dallas Baptist University. He could speak the language of younger pitchers.

“These guys are used to using that stuff before they even get into pro ball,” Falvey said. “So now a coach is required, at this stage, to know a little about that to help the player. Because he is going to use it.”

The Twins have surged to a sizable lead in the American League Central. Working in concert with 33-year-old assistant pitching coach Jeremy Hefner, Johnson has sharpened the approach of Jose Berrios and helped revive Martin Perez. He arrives at meetings armed with data and interested in discourse.

“Whenever I’m talking to these guys and I’m trying to change a delivery or change a pitch usage or change a grip or whatever, if I don’t have the ‘why?’ they’re not going to buy in,” Johnson said. “So having an understanding of TrackMan and biomechanics — this and that and the other — is the way you connect with them today.”

The technological advances make modern pitching sound esoteric to the casual fan. Dodgers pitcher Ross Stripling outlined the arcana when explaining how his 24-year-old teammate Walker Buehler analyzes outings.

“He can go out there and throw six shutout innings, but he’ll come in and look at the axis that his slider was spinning off of, and the spin rate of his curveball, and the rise on his fastball,” Stripling said. “And if it’s not what he wants to see, he’ll be like ‘I lucked out.’ Versus if he goes six innings and gives up eight runs, if he comes in and see all his stuff lines up on the TrackMan, he’ll be like ‘I killed it. It just wasn’t my day.’”

Sign up for our daily sports newsletter »

It falls to Dodgers pitching coach Rick Honeycutt to connect with pitchers like Buehler, but also Rich Hill, who at 39 is the eldest in the majors. This is Honeycutt’s 14th year on the job. By his third, he had discerned that players learned more with visual cues than with verbal ones. As the seasons pass, he remains effective because of a blend of acumen and persuasion.

His philosophy aligns with his boss, president of baseball operations Andrew Friedman. Friedman values transparency with his players. This connects them to the organization’s larger goal of winning championships, which aligns with Bosche’s third motivational tenet.

“I firmly believe that a more confident and comfortable player performs better,” Friedman said. “And so they gain confidence and feel more comfortable when they feel like they understand what’s going on, and the ‘why?’ of certain things.”

Baseball used to be more rigid, Hill indicated. He was born in the spring of 1980, 10 months before Ronald Reagan’s inauguration. He is one of only five current major leaguers who is also a member of Gen X and the only starter who warms up to Pearl Jam’s 1991 grunge touchstone “Even Flow.” He debuted with the Chicago Cubs in 2005 — an era that already feels distant, he said.

“Coming up, it used to be like ‘Why the hell can’t you throw strikes?’ ” Hill said. “Not with everybody — I’m not going to blanket statement all coaches. But now, the environment of major league clubhouses, when a guy gets called up, is much more conducive toward productivity out on the field than it used to be.”

The change has been subtle and incremental. The culture did not shift from cruelty to kindness overnight. But as teams seek to gain the advantages at their disposal, they learned to divest themselves of dogma and unproductive tradition.

The coaches who remember earlier eras may miss them. Those who remain in the sport understand their purpose is to aid their players above all.

“All I’m doing is trying to pass on what I know to be a fact to these young kids,” Washington said. “They need us. They need people like me. They need people like other coaches who have been through it, and can understand how to arrive at what they want to do in life — and that’s be a tremendous baseball player.”

Twitter: @McCulloughTimes

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.