It’s ‘a miracle’ that Chargers Coach Anthony Lynn is alive

The fractured memory washes over Anthony Lynn in a series of gruesome snapshots. A flash of headlights. Cold asphalt. Blood pooling around him. A frantic ambulance ride.

“The doctors didn’t understand how I survived,” said Lynn, 48, new coach of the Chargers.

In truth, no one could explain it.

The Dallas Cowboys had just broken training camp in Oxnard on Aug. 20, 2005, and Lynn was out to dinner in Ventura with a group of fellow assistant coaches. As he was crossing a normally quiet street, he was struck by a speeding drunk driver, who had exited a freeway off-ramp. Lynn, a former NFL running back, flew 40-50 feet into a parked Volkswagen, totaling that car.

Todd Haley, Cowboys receivers coach at the time, had crossed the street just ahead of him and witnessed the horror.

“I knew the car was coming fast and I heard a sound and thought it had hit some trash cans or something,” recalled Haley, now offensive coordinator of the Pittsburgh Steelers. “When I turned and looked, Anthony was cartwheeling through the air. Then I watched him hit head first into the mirror of a parked car that was along the street.

“I had to run probably 20 yards to get to him. I’m thinking he’s dead for sure as I’m running and yelling. There were a lot of people walking around, and I’m yelling. The car stopped for a second and then took off. I’m yelling, ‘Call an ambulance! Call the police! Go after that guy! Get towels!’ It was awful.”

The driver, Sergio Sandoval, was apprehended and arrested shortly thereafter, his blood-alcohol level three times the legal limit. He was convicted on felony hit-and-run charges.

Lynn suffered two collapsed lungs, three broken ribs, major facial and shoulder damage that required four surgeries, and temporary paralysis. But somehow he lived, spending only two weeks in the hospital.

“As a young kid growing up and as a teenager, you listen to all the sermons and hear about the miracles, and it’s almost like, ‘I don’t see that stuff happening today. I don’t see no miracles,’” he said. “This was a miracle.”

More than a survivor, Lynn is now a pioneer. He’s the first African American head coach in Chargers history, and an overnight success 17 years in the making. From 2000 through the first two games of this season, he was a position coach — mostly in charge of running backs — for Denver, Jacksonville, Dallas, Cleveland, the New York Jets, and Buffalo.

But after the Bills started 0-2 this fall, then-coach Rex Ryan fired Greg Roman as offensive coordinator and replaced him with Lynn, who already had the dual title of running backs coach and assistant head coach. Buffalo tore off four wins in a row before losing seven of its final 10, a slide that cost Ryan his job with one game left. Lynn was promoted to interim coach for the finale, a loss to the Jets.

Lynn, who had never been a play-caller before this season, said the whirlwind of promotions “was all the things you wanted to accomplish in your career — you just don’t expect them all to happen in one season.”

Only days after he was hired did Lynn learn of the historic significance. He had long believed that the NFL’s Rooney Rule, put in place to encourage the hiring of minority coaching candidates, had become a perfunctory exercise of checking a box then moving forward with a predetermined hire.

I think the intentions of the Rooney Rule are good. I just think some people abuse the spirit of it.

— Chargers Coach Anthony Lynn

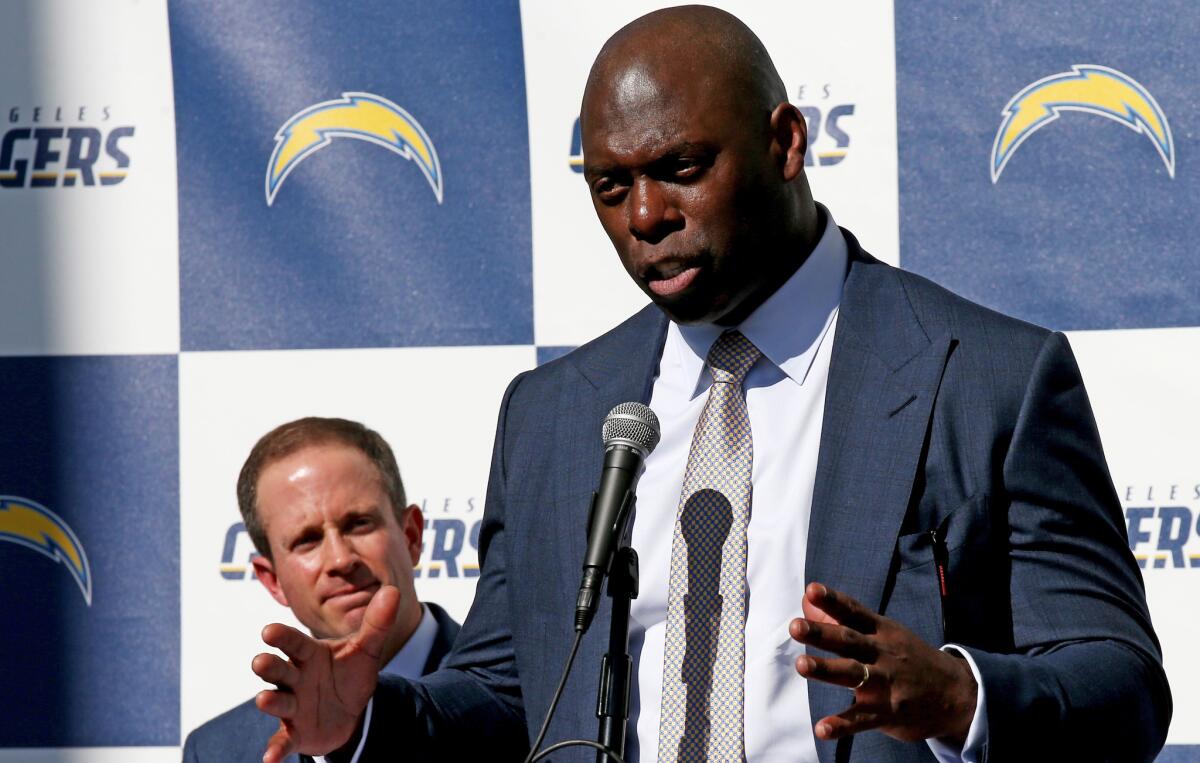

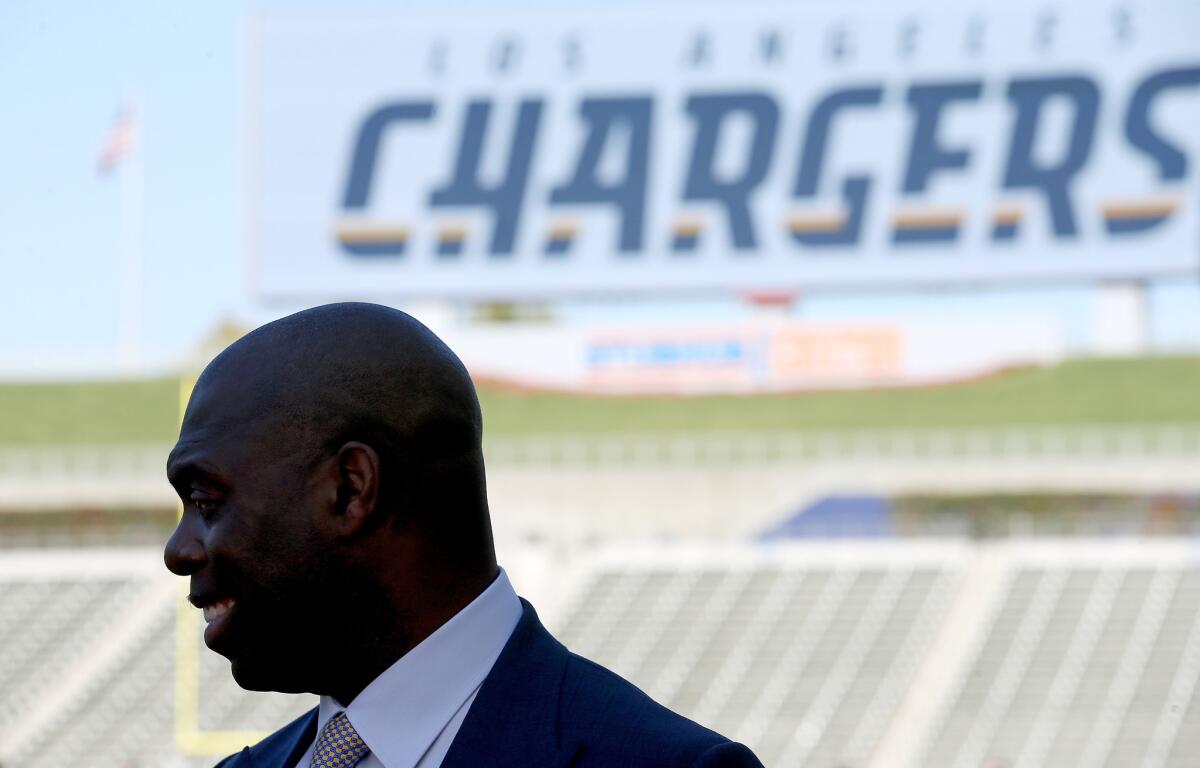

New Chargers Coach Anthony Lynn looks around StubHub Center in Carson following a news conference to announce his hiring on Jan. 17.

“I think the intentions of the Rooney Rule are good,” he said. “I just think some people abuse the spirit of it. I wanted teams to do their homework, investigate, then hire the best man for the job. Go through the process.”

Lynn, who spent six seasons as an NFL running back, including backing up league most valuable player Terrell Davis on two Super Bowl teams in Denver, developed his tireless work ethic growing up in Celina, Texas, a 45-minute drive north of Dallas.

Because his father wasn’t around, his main male role model was his maternal grandfather, Tommy Lynn, a farmer and a onetime Negro League baseball catcher.

“They said my grandfather talked more smack than anybody,” Lynn recalled. “He was a jokester. He could get in anybody’s head. I remember as a kid looking through a peep hole in my room and watching him hold a microphone at a party. Standing in front of the room, he was like a comedian. He was telling jokes, had everybody in the house dying laughing. My friends would come home from college just to visit with him, and they would say he missed his calling, that he should have been a comedian.”

When it came to his job, the elder Lynn was all business. He plowed fields with tractors, tended to horses and cattle, worked from 7 to 7 each day.

“There wasn’t a day I can remember he didn’t work,” Lynn said. “He’d drag me out in the summers to work with him. Breakfast was at 6:15. I showed up at 6:30 one morning and breakfast was gone. He was just letting me know that, hey, there’s a standard and expectation, and he’s going to hold you to it. Accountability was big with him.”

That, naturally, is a tenet of Lynn’s coaching style. He’s about accountability, and keeping the Chargers focused on the task at hand, despite the outside turbulence of the team leaving San Diego after 56 years and relocating to Los Angeles.

Lynn regrets that, although his grandfather got to see him play at Texas Tech, Tommy Lynn died before seeing him play in the pros.

“He passed my rookie year,” Lynn said. “I wanted to become a professional athlete so bad because he had encouraged me for so long. When I became one, he didn’t live to see it. But I went on and had a successful career with him in my memory.”

More important, Lynn is alive.

“My mom would tell me, ‘There’s miracles every day, you just don’t know about them,’” he said. “I’ll be damned if that wasn’t true.”

Follow Sam Farmer on Twitter @LATimesfarmer

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.