When soccer teams from El Salvador and Honduras met 50 years ago, it really was a war

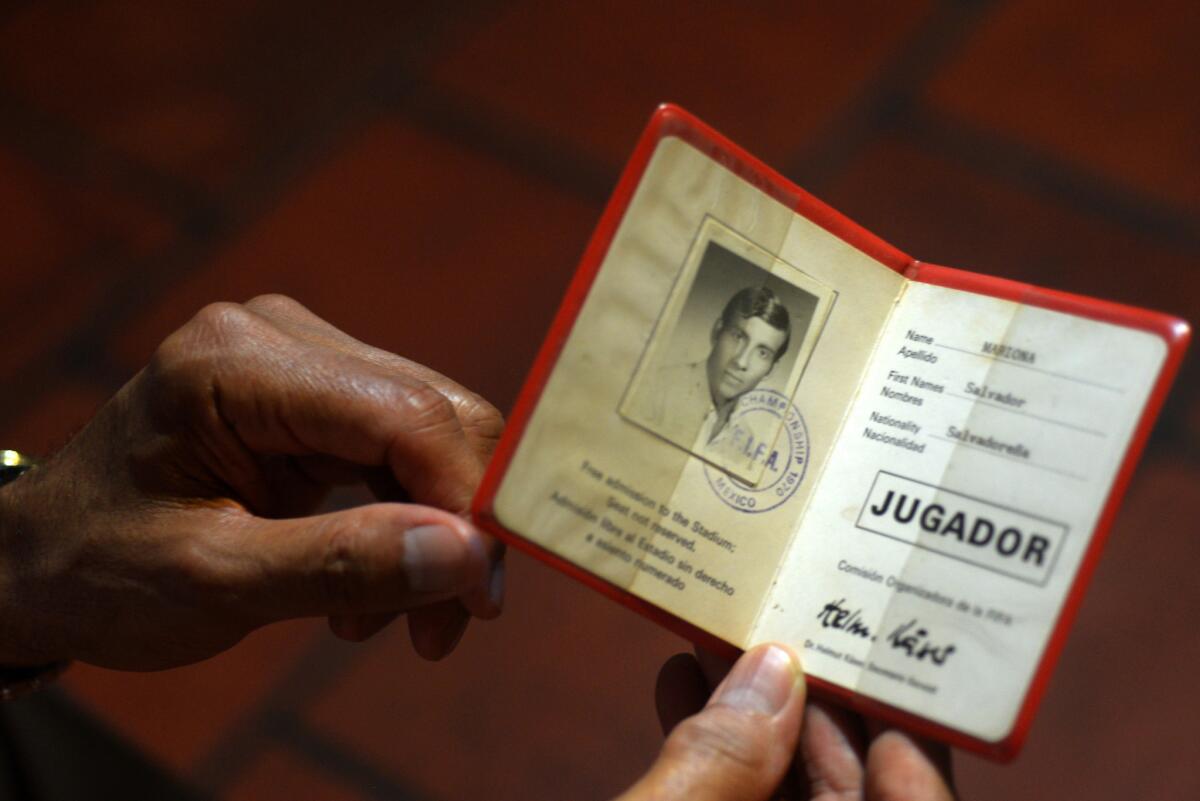

Five decades later, Salvador Mariona vividly recalls the sights and sounds from a soccer win over Honduras that sent El Salvador on to a historic appearance in the World Cup.

“What I remember is how fabulous it was for us soccer players and for the Salvadoran people,” says Mariona, who during his playing days was a tall, sturdy defender with a broad nose and a tense, piercing stare.

Three weeks later, the joy turned to pain when the Salvadoran army invaded Honduras, the start of a deadly four-day conflict that became known as the Soccer War. The ramifications from that era are still felt today, from Central America to Los Angeles and beyond, as the teams prepare to meet again Tuesday at Banc of California Stadium.

Mariona, now 75 and slightly stooped, his once-penetrating gaze muted by thin-frame glasses, remembers that fight too. And he says history called it wrong.

“Football had absolutely nothing to do with it,” he thundered in Spanish during a recent phone interview from San Salvador. “I tell you this because I, as captain, feel involved when they say that we were the culprits of the Football War. This was a political issue similar to what is happening today with the migrants who are arriving in the United States.

“It was sad for everyone, for Honduras and El Salvador.”

This week’s game in Los Angeles is part of the CONCACAF Gold Cup, where the stakes will be much lower than they were in 1969. Back then, the Central American neighbors met in a best-of-three series that determined which country would advance toward becoming the first from Central America to qualify for the World Cup, soccer’s most important competition.

But the political stakes today are no less tense. When Nayib Bukele was sworn in as Salvador’s new president earlier this month, he pointedly left Honduran leader Juan Orlando Hernandez, whom he has called an illegitimate dictator, off the guest list.

“I was very surprised by the words of the president-elect of El Salvador,” said Marco Antonio Mendoza, who played for Honduras 50 years ago. “Hopefully they will not affect the future, because there are still people who do not forget the past.”

In 1969, the contentious issues were primarily immigration and land reform. Honduras, which is five times larger in area than El Salvador, had nearly 700,000 fewer people. As a result of the overcrowding, more than 300,000 Salvadorans crossed the border, taking factory jobs, farming and, in many cases, marrying into Honduran families.

Sign up for our weekly soccer newsletter »

Rural Hondurans came to resent the immigrants, who they said took jobs and land, fueling a nationalist backlash.

That was the climate in which the first World Cup qualifier kicked off in Tegucigalpa, the Honduran capital, on June 8.

The night before the game, Honduran fans gathered outside the Salvadoran team’s hotel. “They arrived honking their horns,” Mariona says. “There was music, singing, screaming, doing all that to not let us sleep.”

Honduras beat the weary Salvadorans, 1-0, on defender Leonard Wells’ goal in the final minute of regulation. After, part of the stadium was sent ablaze during rioting.

A week later, the teams met in San Salvador and the scene repeated. The Honduran team’s air force plane was met by hordes of Salvadoran fans. Later that afternoon, the team hotel was surrounded by local supporters who pounded on drums and set off fireworks through the night.

“We put cotton in our ears, but even then we did not sleep at all,” says Marco Antonio Mendoza, a member of that Honduran team. “The next day, very early in the morning, they wanted to knock down the doors of the hotel. Luckily the police there acted quickly.”

Mendoza says players were clandestinely whisked out of the hotel in small groups and hidden around the city; they weren’t reunited until just before the game. Dispirited, exhausted and fearing for their lives, the Hondurans lost, 3-0.

“We’re awfully lucky that we lost,” Honduran star Enrique Cardona recalls. “Otherwise, we wouldn’t be alive today.”

The decisive third game was played in a torrential rain on June 27 in Mexico City. El Salvador won on midfielder Antonio Quintanilla’s goal 11 minutes into overtime, but there was little time for celebrating. That same day, the Salvadoran government broke off diplomatic relations with its neighbor.

“We did not talk about that on the field. There was no problem,” Mendoza says. “But that’s where the famous Football War, which never was a football war, began.”

Carlos Soto Hernandez, a retired Salvadoran general, agrees that the conflict had little to do with soccer. “It was not the Football War,” he says during a phone interview. “It was the war of national dignity.”

Yet, three days before the game in Mexico City, the Salvadoran government issued a resolution blaming rising tensions and violence in Honduras on the results of “recent international football games.” Weeks after that final game, its army pushed across the border, overwhelming the Honduran military and launching attacks on the main road between the countries before pushing toward Tegucigalpa.

Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza provided weapons and ammunition to Honduras, but that didn’t stop the Salvadoran advance. Honduras, fearing its capital would be overrun, appealed to the Assn. of American States to intervene.

A cease-fire was quickly arranged, and four days after the war began it was over.

Though short in duration, the consequences were significant. More than 250 Honduran soldiers and 2,000 civilians were killed and thousands more were left homeless. There were similar casualties among Salvadorans, and some 100,000 were forced back across the border. Additionally, the conflict took an economic toll on both countries.

Still, much of the world missed it, its attention diverted elsewhere: Two days after the invasion began, the Apollo 11 spacecraft had lifted off from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida; the Salvadoran army was still in Honduras when Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong touched down on the moon.

What followed was social unrest that led to a civil war throughout the 1980s and into the ’90s in which the Salvadoran military, emboldened by its success in Honduras, brutally put down. More than 75,000 were killed in that conflict, and since then 2 million have fled — approximately 1.4 million to Los Angeles County, according to government figures. Remittances from the U.S. now account for nearly one-fifth of the Salvadoran GDP.

In soccer, Central American countries have now made 10 appearances in the last 10 World Cups. The team from El Salvador became the first, following its 1969 win over Honduras with a qualifying-series win over Haiti.

“The experience was sensational, wonderful,” says Mariona, who retired from soccer to become an insurance salesman, eventually founding his own company. “We did not win anything” — the team didn’t score in three losses — “[but] imagine being the first country in Central America who qualified.”

Mariona says members of those Salvadoran and Honduran national teams decades ago, embarrassed that soccer had been blamed for the “Football War,” tried to play a role in reestablishing a peace — difficult since the countries and their national soccer federations didn’t speak for more than a decade.

“Very few people traveled to El Salvador and very few people came here,” says Mendoza, who played for Honduras. “The truth is, innocent people died. There were no friendly matches, the games stopped completely.”

But the players stayed in touch, and after a magnitude 7.6 earthquake struck El Salvador in 2001, Mariona says veterans of the 1969 teams played a series of charity games to raise money for quake victims.

“We are still friends,” he says. “They treated us wonderfully and also when they came here. We did not have any problem or reproach from the fans.”

Fifty years later, details about that historic soccer series between El Salvador and Honduras have largely been forgotten — if they were ever known — by the players who will participate in the game at Banc of California Stadium on Tuesday.

“I don’t know anything about that,” says Honduran forward Romell Quioto, who was born 22 years after the war ended.

He does, however, know any game against El Salvador is something special.

“We’re neighboring countries so there’s a rivalry,” he says. “There’s a lot of passion involved.”

kevin.baxter@latimes.com | Twitter: @kbaxter11