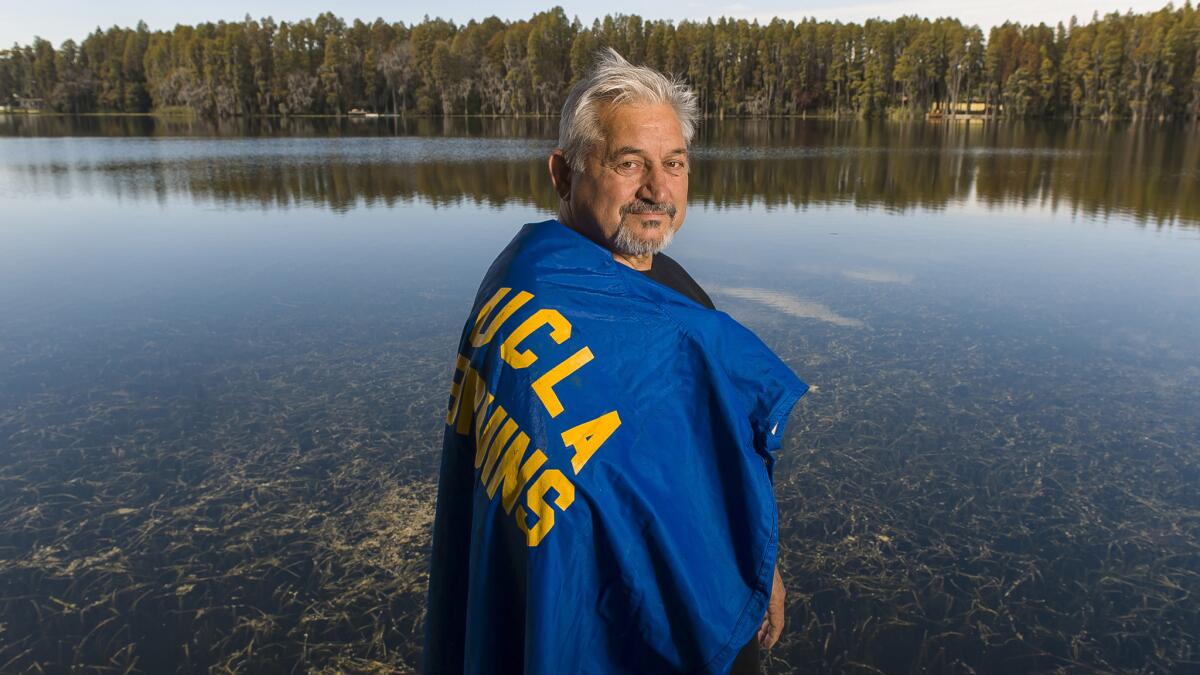

UCLA’s Zenon Andrusyshyn kick-started his life after 1967 loss to USC

Zenon Andrusyshyn became curious when he saw the flames upon his return to the UCLA campus.

UCLA had lost what had been billed as “The Game of the Century” to USC, 21-20, that afternoon.

There was a clear hero of that 1967 game. O.J. Simpson had zigzagged across the Coliseum turf on his game-winning 64-yard touchdown run.

And, as Andrusyshyn was about to learn, there was a clear goat. Him.

The sophomore kicker had missed one field goal, had two others blocked, and failed on a crucial extra-point attempt, leaving the Bruins with a precarious 20-14 fourth-quarter lead.

After the game, Andrusyshyn didn’t come back on the bus, feeling uncomfortable about riding with the team. He became more uneasy after a friend dropped him near the student union.

“I saw students burning someone in effigy,” Andrusyshyn said. “As I got closer, I saw there was a ‘Z’ on the shirt.”

The self-described “arrogant guy,” who hung out with Hollywood stars and starlets, wanted to disappear. He says he wore disguises on campus for sixth months. He graduated in 1970, but not before venting at the team banquet.

Yet, from those burned-in-effigy ashes evolved a different man.

Andrusyshyn, 67, still occasionally hears about his misses that day. But he is living proof that no matter how crushing a defeat may seem in this annual city football rivalry, no man’s future need be destroyed by one game.

Zee, as he was known, spent 16 seasons in professional football while turning his life around. He was the director of Tampa’s Fellowship of Christian Athletes for 20 years, then founded his own ministry. He has traveled to Panama to deliver medical supplies. He brought cancer medication to children in the Chernobyl area. He has spent decades counseling youths, often using his own life as a cautionary tale.

“Football becomes very minor when you see what Zee has done,” said Gary Beban, UCLA’s quarterback in 1967. “His life after UCLA became far more important than a couple of kicks.”

The man

Andrusyshyn was born in a German refugee camp in 1947, to teenage parents who had fled Ukraine because of communism.

“Every time my mom talked about the war, she started crying,” Andrusyshyn said. “She saw people murdered, towns emptied, people sent to concentration camps. I learned not to bring it up.”

The family emigrated to Canada when Zenon was 3. Andrusyshyn became a talented track athlete who held the Canadian record in the javelin. He came to UCLA with his sights on the 1968 Olympics, but an arm injury led him to football.

He developed a cocky and carefree attitude along the way.

Andrusyshyn told anyone who would listen about a dream he had in which an angel gave him a golden shoe. He wanted to wear gold cleats in games, but Bruins coach Tommy Prothro wouldn’t allow it.

“He was different,” said Wes Grant, who played for the Bruins in 1968 and 1969. “He wasn’t a bad guy.”

Andrusyshyn recalls things differently. “I was out of control and full of myself,” he said. “My character was terrible.”

He ran with a Hollywood crowd and, he said, “I was drinking, doing drugs. I was argumentative and didn’t listen to authority.”

Andrusyshyn was also “a fabulous athlete,” according to Gordon Bosserman, who played at UCLA from 1967-69.

After his arm injury, Andrusyshyn went to Prothro to ask for a tryout. He recalls the coach’s response as, “Do they even play football in Canada?”

“Zee comes out and started kicking over this big fence at the practice field,” said Greg Jones, who played at UCLA from 1967-69. “Tommy had those big, thick glasses and I could see his eyes getting wider and wider.”

Andrusyshyn secured a spot on the team with a 62-yard field goal during the spring game.

The game

UCLA special teams got their work in before the rest of the team practiced in those days. Andrusyshyn would leave early.

“No one on the team really knew Zenon,” Jones said.

He was a premier punter, but as a field-goal kicker he was erratic, making only 11 of 24 kicks in 1967.

Still, his three field goals, one from what was then a school-record distance of 52 yards, allowed UCLA to salvage a 16-16 tie with Oregon State to keep the Bruins’ national title hopes alive. UCLA was 7-0-1 and ranked No. 1 in the nation entering the USC game. The Trojans were No. 4.

“Zenon just had a bad day,” Beban said.

Andrusyshyn missed a 32-yard field-goal try, and Bill Hayhoe, USC’s 6-foot-8 lineman, blocked two of his attempts. When UCLA took a 20-14 lead, Andrusyshyn, wary of Hayhoe, chipped the extra point wide left.

“I missed by five or six inches,” Andrusyshyn said.

USC Coach John McKay said that Andrusyshyn had a low trajectory on his kicks, which was why Hayhoe was used. Bosserman scoffed at that, saying, “Sure sounds brilliant, doesn’t it?”

UCLA fans wasted little time in singling out Andrusyshyn.

“They should have had me in the noose with him,” said Beban, who won the Heisman Trophy that year. “I had 10 minutes to win that game and didn’t get it done.”

Andrusyshyn was supported by the vast majority of his teammates.

“There was no secret a lot people disliked him,” Bosserman said. “They forgot his kicking kept us in a lot of games.”

To safely navigate the UCLA campus, Andrusyshyn said, “I bought a fake mustache and wore funny hats. I didn’t introduce myself to anyone.”

That didn’t fool everyone. The next spring, Andrusyshyn was stopped on his way to a class.

“It was John Wooden,” Andrusyshyn said. “He said, ‘I wanted to let you know I’m pulling for you. Don’t quit.’”

He didn’t, but his emotions continued to percolate until they boiled over at a team banquet in 1969.

Andrusyshyn directed a blistering speech at the university, Prothro and UCLA athletic department officials. It began, “I wore good old No. 7 for UCLA. My job was to blow important kicks. . . .” Not satisfied, he ranted some more to Los Angeles Times columnist Charles Maher, saying that at UCLA, “you missed a kick and people would look at you like you were a deviant or something.”

Said Andrusyshyn: “I burned every bridge.”

The minister

Andrusyshyn met his wife on “The Dating Game” in 1969.

He was Bachelor No. 3. She picked Bachelor No. 1. But he didn’t give up easily.

“He waited for me after the show,” Susan Andrusyshyn said. “He was this big burly guy with a Fu Manchu mustache.”

She was wary, but when they crossed paths again six weeks later, she agreed to a date. They went to lunch; she paid.

“He said he wanted to make it up to me by taking me to dinner,” Susan said. “When we went out again, I said, ‘Let me see your wallet first.’”

They have been married for 40 years and raised two children.

Andrusyshyn dabbled in acting. He had small part on the TV show “Medical Center” in 1969. That episode’s main guest star: O.J. Simpson.

He was drafted by the Dallas Cowboys in the ninth round in 1970 but was cut before the end of training camp. Andrusyshyn recalls Tom Landry, the Cowboys’ legendary coach, summoning him.

“He told me I was nothing but problems and the Dallas Cowboys don’t want problems,” Andrusyshyn said.

Andrusyshyn had a long career as a punter and kicker in the Canadian Football League, the United States Football League and one season with the NFL’s Kansas City Chiefs, in 1978.

Meanwhile, he worked at improving himself off the field.

He and Susan attended an Athletes in Action meeting in 1974 “where we got saved,” his wife said. Zenon says he has annually made “150-200 speaking engagements” since.

Overseas missions were his off-season job. He and Susan brought aid to the Kuna Indians in Panama in the 1970s. After a trip to Ukraine to provide medicine after the Chernobyl nuclear accident, they brought back 15 children to Florida to be checked for cancer.

While working for the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, Andrusyshyn completed his master’s degree at Dallas Theological Seminary in 1994.

He saw Landry again in 1990, at an FCA conference. Landry was so impressed that he came to Tampa to participate in events.

In 2007, Andrusyshyn founded Zenon Ministries.

“You have nothing but respect for what he has accomplished,” Jones said.

However, there are still people who remember him for only one thing.

“We have met people and they will go, ‘Ah, you’re the guy who missed those kicks,’” Susan Andrusyshyn said. “What’s wrong with people? Why do they associate him with some dumb, stupid kicks?”

Andrusyshyn understands, but he wouldn’t change history.

“I would not trade that for anything, even though we lost,” he said. “That experience was the turning point. I had to get my life in order. It took me another seven years, but I figured it out.”

Twitter: @cfosterlatimes

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.