Todd McNair’s defamation lawsuit against the NCAA is finally going to trial. Here’s what you need to know:

Todd McNair’s journey to the fifth-floor courtroom at the Stanley Mosk Courthouse in downtown Los Angeles has taken almost seven years.

The former USC running backs coach sued the NCAA for defamation in June 2011 after sanctions in the Reggie Bush extra benefits case essentially ended his career.

After legal detours and delays of almost every variety, jury selection in McNair’s case is scheduled to begin Wednesday in L.A. County Superior Court. Opening arguments are expected to follow a day or two later.

The trial, which is expected to last three weeks, will include reams of documents, a dozen witnesses, headlined by McNair, and depositions from current and former NCAA officials who played key roles in the USC investigation.

And one of the most contentious episodes in NCAA’s enforcement history will be revived, one email, one phone call, one career at a time.

Here’s a closer look at the case:

What happened?

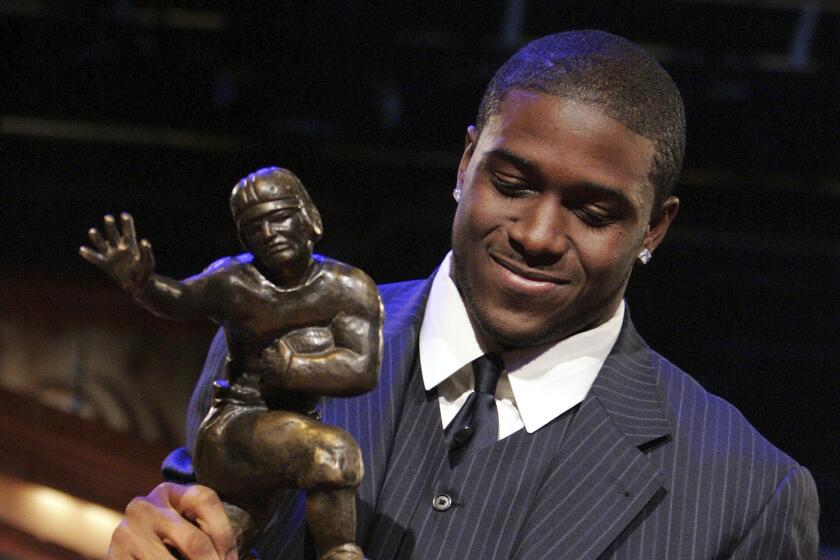

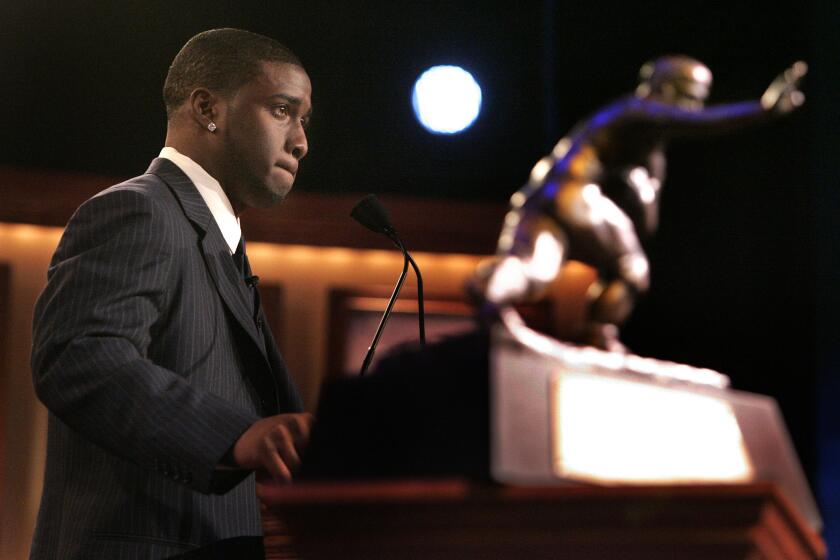

After an investigation that lasted more than four years, the NCAA’s Committee on Infractions ruled in June 2010 that Bush, a former Trojans running back, and his family received illicit benefits from sports marketers. The committee handed down historic sanctions including a two-year bowl ban, the loss of 30 scholarships and four years of probation. It also found that McNair, USC’s running backs coach from 2004 to 2010, engaged in unethical conduct. The NCAA issued a one-year “show-cause” order that essentially left him unemployable by USC or any other school. USC didn’t renew his contract in 2010. McNair hasn’t coached at the college or professional level since.

How did this end up in court?

McNair sued after the NCAA rejected his appeal, alleging that the organization fabricated evidence and defamed him by saying he engaged in unethical conduct.

Why has the case taken so long?

This one even stretches the proverb about the wheels of justice turning slowly. Start in November 2012, when Judge Frederick Shaller rejected the NCAA’s motion to dismiss the case. After reviewing internal NCAA emails, the judge concluded that the actions of the organization’s investigators were “over the top” and the infractions committee showed “ill will or hatred” toward McNair.

The NCAA asked California’s 2nd District Court of Appeal to reconsider the decision — and that the appellate court keep more than 700 pages of emails, deposition excerpts, phone records and other documents under seal. The Los Angeles Times and New York Times filed an application with the court to unseal the cache. The appellate court rejected the NCAA’s attempt to seal the documents in February 2015 in a strongly worded opinion and they became public later that year.

Ten months later, the appellate court dealt the NCAA another blow and ruled that McNair “demonstrated a probability of prevailing” in his lawsuit and therefore his case could move forward.

“McNair made a sufficiently convincing showing that the NCAA recklessly disregarded the truth when the [infractions committee] deliberately decided not to correct the investigation’s errors or to acquire more information about what McNair knew concerning the rules violations, even after McNair notified the Appeals Committee of the errors,” Justice Richard Aldrich wrote in the opinion.

California’s Supreme Court denied a petition by the NCAA to review the decision.

The parties returned to the appellate court in 2016 during the NCAA’s unsuccessful attempt to remove Shaller, who graduated from USC, as the case’s judge.

Who will testify?

McNair is the biggest name among the dozen witnesses scheduled to testify. He’s kept a low profile since filing the lawsuit. Four members of the infractions committee that sanctioned McNair and USC — lawyer Brian Halloran, Temple law professor Eleanor Myers, Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference Commissioner Dennis Thomas and Missouri law professor Rodney Uphoff — could also testify. Same with Angie Cretors, the NCAA’s former director of agents, gambling and amateurism activities, who played a key role in the investigation.

What about NCAA President Mark Emmert?

After Shaller rejected the NCAA’s attempt to block Emmert’s deposition, McNair’s attorneys questioned the president earlier this month. At issue is a statement Emmert made to USA Today in December 2010: “Everybody looks at the Reggie Bush case and says, ’It took them a long time.’ But they got it right, I think.” In a court filing, McNair’s attorneys described the comment as part of the “character assassination of Mr. McNair.”

While Emmert’s deposition is subject to a protective order — meaning you won’t be reading the transcript in The Times — it can and will be used during the trial. So will depositions of nine other key figures, including former NCAA investigators Richard Johanningmeier and Ameen Najjar and members of the infractions committee, including Nebraska law professor Jo Potuto.

Could any other notable names be mentioned?

Definitely. Both parties suggested the court inform jurors of 29 other people whose names might come up during the trial. They include Bush and former USC coaches Pete Carroll, Lane Kiffin and Steve Sarkisian.

What evidence might be introduced?

The joint exhibit list mentions 867 items. Copies of checks to Bush. NCAA manuals and press releases. Messages posted on the WeAreSC fan website. McNair’s office phone records from USC. Vehicle registration records. A diagram of the room setup for the infractions committee hearings. A letter from then-USC President Steven Sample to infractions committee chair Paul Dee in February 2010. Transcripts of interviews with Carroll and a slew of others. Newspaper articles. A chart of phone calls between Bush and McNair. Emails between members of the infractions committee. And much more.

What evidence could generate the most attention?

Both sides will use emails between members of the infractions committee.

Among the messages is an eye-opening note Myers sent to other committee members in March 2010, alleging the NCAA enforcement staff “botched” a key interview with McNair and he “did not have a good opportunity” to explain a phone call with sports marketer Lloyd Lake in January 2006 that the NCAA used as key evidence in the case.

In the email, Myers described the interview as “generally a very confusing piece of questioning” and said she wasn’t “comfortable charging him with lying.”

An NCAA investigator questioning McNair misstated the year of the two-minute phone call — 2005 instead of 2006 — and said that McNair initiated the call, though records showed otherwise. McNair’s attorneys accused the NCAA of using the phone call to punish McNair and as the basis to sanction USC.

That brings in a second key email from Shep Cooper, the NCAA’s liaison to the infractions committee, to Uphoff in February 2010.

“As [infractions committee member] Roscoe [Howard] said at some point during the Sunday morning deliberations, individuals like McNair shouldn’t be coaching at ANY level, and to think that he is at one of the premier college athletics programs in the country is outrageous,” Cooper wrote. “He’s a lying, morally bankrupt criminal, in my view, and a hypocrite of the highest order.”

Cooper and Howard were both deposed; those depositions will be used during the trial.

“What occured here,” McNair’s attorneys wrote in a court document during the appellate process, “is malice personified.”

Will the trial affect the NCAA sanctions against USC?

No. Though a slew of details about the infractions case will probably be revisited, the trial is about whether the NCAA defamed McNair. That’s it.

USC assailed the NCAA in 2015 after the release of the first batch of documents the organization wanted to keep under seal, but never took legal action.

What does McNair want?

He’s seeking unspecified damages for loss of reputation and a variety of other counts in addition to interest, legal fees and punitive damages.

Will this trial end the McNair-Bush-NCAA saga?

Whichever side loses is almost certain to appeal. If the case lands in the appellate court (or even the California Supreme Court), final resolution could be years away.

Twitter: @nathanfenno

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.