The Oregon-ification of college football has hurt one team the most: Oregon

In 2009, at the same time Chip Kelly was taking his first head coaching job at Oregon, defensive tackle Stevie Tu’ikolovatu was beginning his first season at Utah.

He left on a church mission to the Philippines the following year, and when he returned in 2013 he found college football had upped and got itself in a big hurry.

“Teams are trying to get the ball more to the perimeter than trying to just tough it up and go up the middle,” said Tu’ikolovatu, who transferred to USC this season. “And they’re just trying to beat everybody with fast tempo.”

It was all Kelly and his new blur offense, an ultra-fast spread scheme that soon assumed almost mythic status. Coaches began a pilgrimage to Eugene, Ore., to observe. There were stories of defenders, tongues aslant, begging for mercy. In Kelly’s first season, the Ducks put up 47 points on Pete Carroll and USC, churning through 613 yards of turf.

Oregon rode the innovation to four Pac-12 Conference titles, three Rose Bowls and two national championship game appearances over seven seasons.

But college football is cyclical. Teams adapt. Kelly birthed college football’s greatest innovation in decades, but for Oregon, its dominance has been relatively short-lived.

When Tu’ikolovatu returned from his mission, Kelly was in the NFL and it wasn’t just Oregon running the blur anymore. Many other programs had scavenged scraps — teams such as Ohio State, Mississippi and even previously staid Alabama.

On Saturday afternoon at the Coliseum, USC will play an Oregon team whose competitive advantage has decayed to a 3-5 record. In some ways, Saturday’s USC team, like many teams across the country, will look more like a 2009 version of Oregon than a 2009 version of itself.

USC will run the zone read and incorporate run-pass options. Managers will hoist giant placards to call plays or serve as decoys. At some point, the offensive coaches will get animated, waving their arms like over-exuberant third-base coaches. That’s when USC will go up-tempo.

“Chip’s one of those guys I think revolutionized the game and probably changed the college game forever,” USC Coach Clay Helton said.

The change took some time. Helton said it took a year before the first teams started catching on.

“You had to learn how to control it, and see how to cover that much grass,” Helton said. And it was longer before coaches could recruit the right offensive personnel to mimic it and the right defensive personnel to stop it.

Change was incremental but marked. The average college football game now includes almost nine more plays per game than in 2009. The average total score is more than 10 points higher.

“Oregon started speed, going fast, and I think that’s become a staple of everybody’s offense,” USC safety Chris Hawkins said. “I think we’ve seen their type of plays all season.”

Three of USC’s last four opponents — Arizona, Arizona State and California — have pilfered parts of Oregon’s style. They have been doing so for years.

So why is this the season that Oregon has returned to earth? In part, because Oregon’s defense is the worst it has been in at least a decade. But it’s also because the nation’s offenses needed time to perfect Kelly’s scheme.

Before taking over at Ohio State in 2012, Urban Meyer visited Oregon and found the system difficult to replicate.

“Everyone talks about their shovel passes, or whatever,” Meyer said. “It’s not that. There’s a culture out there that has been started.”

Meyer was so diligent about becoming more like Oregon that he made his coaching staff rehearse its new practice methods, without players, before that first training camp began. It worked. Ohio State went 12-0 that season.

For coaches less intent on immediate Oregon-ification, results took longer — until this season in some cases.

Since last season, scoring has skyrocketed by almost three points per team each game, the biggest jump this decade by far. For Oregon, that’s the difference between 3-5 and 6-2. The Ducks, Helton noted this week, lost heartbreakers to Nebraska, Colorado and California.

The margin in each? Three points.

Oregon’s offense hasn’t been the issue. It is producing numbers only slightly below its average.

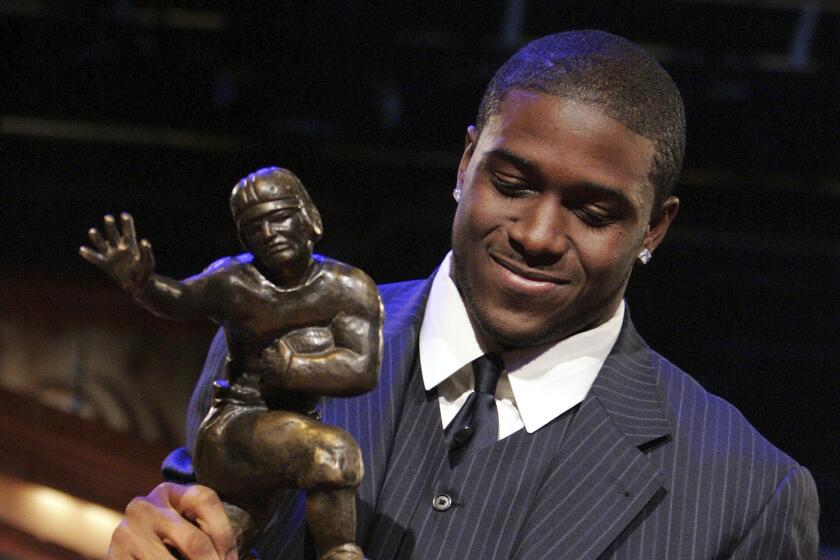

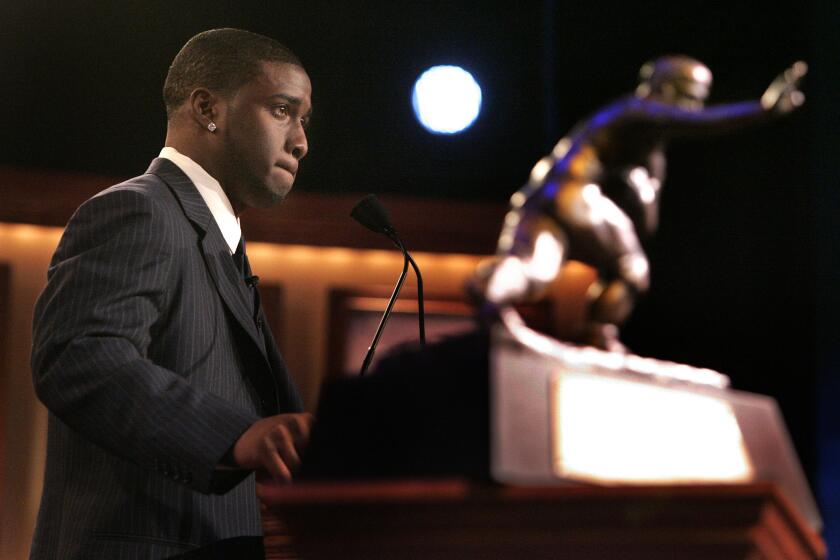

Asked whether Oregon looked distinct from other teams USC has seen, Trojans cornerback Adoree’ Jackson paused and thought.

“I think they’re different because …” he said. Then he laughed. “Their uniforms.”

Helton said Oregon Coach Mark Helfrich has introduced wrinkles that have kept Oregon unique in some aspects. USC’s defenders said any competitive advantage Oregon’s offense has retained is through recruiting. It still has Nike cachet and facilities, and its status as the Kanye West of uniforms — purposefully bizarre, big with the kids — attracts talent. Oregon has only failed to crack the top-25 recruiting ranks just once since 2009.

“They’ve always got the best skill position-wise team that we’ve seen,” Hawkins said. “Their skill set at each position is kind of crazy.”

Jackson said players still view Oregon as the mecca of speed.

“Everybody fits their mold of what they want to do,” he said.

Oregon’s biggest impact might be on the nation’s defenses.

The first coach to effectively counter Oregon was USC coordinator Clancy Pendergast, then at California. He took a risk: cover-zero defense, force Oregon to pass. The Ducks won, but managed only 15 points.

Such a strategy is more difficult now. Oregon has recruited more capable passers. Freshman quarterback Justin Herbert has thrown for 12 touchdowns in three starts.

But more wholesale changes have taken shape. At USC, the defensive playbook is simpler. A new type of defender roams the field, what Helton calls the “walk linebacker” — players such as Leon McQuay III who are strong enough to play like a linebacker but fast enough to cover in space like a defensive back.

Every week, USC runs a “fire drill,” in which the first-team offense runs plays as quickly as possible against the first-team defense. Often, USC goes faster than Oregon’s 13-second goal. In another drill, the defense must sprint to the sideline and back after every play.

“And our service team, I don’t know who gave them wristbands, but they have wristbands now,” Tu’ikolovatu said. “So they’re just running plays like crazy.”

The point is to make parts of every practice feel more like Oregon and its spawn.

“And when it comes to the games,” Tu’ikolovatu said, “then the games feel normal.”

Follow Zach Helfand on Twitter @zhelfand

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.