Mistaken for the enemy

By Ed Park

“If you’ve never programmed a computer, you should,” says Marcus Yarrow, the 17-year-old hacker protagonist of Cory Doctorow’s young adult novel “Little Brother” (Tor: 384 pp., $17.95). “When you program a computer it does exactly what you tell it to do. . . . It’s awesome in the truest sense: it can fill you with awe.”

“Little Brother” is generally awesome in the more vernacular sense: It’s pretty freaking cool. Doctorow is a copyright-reform advocate (“I believe that we live in an era where anything that can be expressed as bits will be,” he writes on his website) who makes his ink-and-paper books available free on the Net under a Creative Commons license; a prodigious op-ed writer and columnist; and an editor of that essential worldwide wonder-cabinet, BoingBoing.net. His immersion in the gadgetry and information-technology debates of our age makes him well-suited to tell a very-near-future tale in which a surveillance-mad government grapples with grass-roots cryptography against the backdrop of a new terrorist attack. But Doctorow’s bona fides would mean nothing if he weren’t also a fluid, instantly ingratiating fiction writer.

Marcus is a San Francisco high school student with a way around every institutional roadblock. He knows how to evade the high-tech gait detectors in his school by putting some pebbles in his shoe, and he has an encyclopedic knowledge of computer and telephone high jinks. (“[D]id you know that it’s really easy to fake the return number on a caller ID? There are about fifty ways of doing it -- just google ‘spoof called id.’ ”)

When the Bay Bridge is blown up, he’s out playing hooky with his friends -- they’re deep into a high/low-tech “Alternate Reality Game” that takes them on an intricate scavenger hunt around the city. Amid the chaos, the teens wind up, separately, in what will come to be known as Guantanamo-by-the-Bay.

His interrogators, who don’t believe that he was just playing a game, subject him to unwarranted, brutal treatment (“I would love to speak to an attorney,” he deadpans), and his best friend, Darryl, fares even worse. Released after a blur of terrifying days, Marcus resolves not to give in to the Department of Homeland Security’s own brand of terror -- its incessant monitoring of citizens’ movements and transactions -- even while his formerly radical father espouses a better-safe-than-sorry position.

Before his capture, Marcus comes across as a smart teen whose anti-authoritarian streak is in line with his demographic. “Little Brother” picks up when even his most mundane activities -- communication, for instance -- are political acts. Suspecting that his homemade laptop has been bugged, he uses his Xbox’s wireless capabilities, and a hacker program called ParanoidXbox, to build a community of like-minded tech-heads who want to operate free of DHS control.

Under his cyberhandle M1k3y, Marcus eventually becomes a celebrity of sorts, though he keeps his identity secret as long as he can. Using cheap devices from Radio Shack, he orchestrates a chaos campaign that messes up the data transmitted by people’s mass-transit debit cards and toll-dispensing FasTraks. The bogus itineraries created are of such strangeness that practically everyone becomes an object of suspicion, and the authorities are overwhelmed by the absurdly high number of cases. Before long he is operating in a world where everything he does is a political act.

Before he became M1k3y -- before the terrorist attack and Guantanamo-by-the-Bay -- Marcus was W1n5t0n, an obvious (though unremarked) nod to the protagonist in George Orwell’s classic nightmare of totalitarianism, “Nineteen Eighty-Four.” Doctorow’s title, of course, is a version of Big Brother, that earlier novel’s collective superego run amok via telescreens and doublespeak, Thought Police and laboriously rewritten history. The allusion in Doctorow’s title was so obvious that I didn’t hit on it till late in the game -- at which point it seemed a little facile, even cutesy.

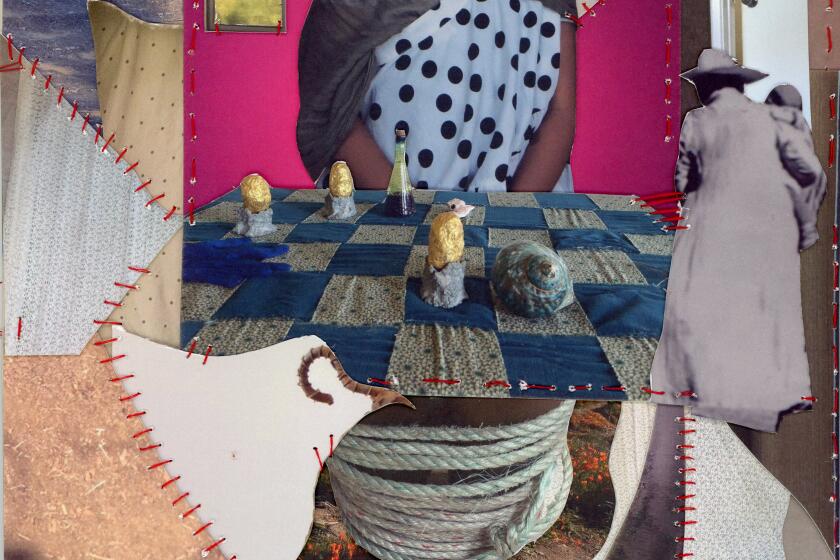

Then it started to seem nonsensical. Especially sitting above the cover art (a trio of our teen heroes in superhero stances, their faces obscured by shadow), “Little Brother” suggests that Marcus is the titular character, but isn’t he the one rebelling? My regard for the book faltered, but then I wondered if Doctorow was up to something subtler. As exciting as Marcus’ adventures are, he’s ambivalent about being the savior, his pronouncements taken as gospel; what began as a quest to rescue his still-incarcerated friend, Darryl, has snowballed into a movement. Perhaps Doctorow means to suggest that Marcus might not be the innocent he relates himself to be -- that speaking truth to power can itself become an intoxicating kind of power.

(A digression: Marcus’ voice is seamless for the most part, but when he says, “My brain was really going now, running like sixty,” I thought: No 21st century teen would say “running like sixty.” In fact, that expression was last in currency at the tail end of the 19th century, in Adenville, Utah, to be precise. That’s where John D. Fitzgerald’s “The Great Brain” books take place; in the first chapter of “The Great Brain,” for example, we see the phrase “working like sixty.” Could this yoking of “brain” and “like sixty” -- I thought wildly -- be an unconscious hommage to those delightful books? And was Marcus, like Fitzgerald’s titular genius, no angel? Maybe less unconscious than I imagined: Thanks to Doctorow’s decision to make his work available online, I was able to riffle through his archives and see that an earlier story of his, “A Place so Foreign,” was in fact set in that same milieu, as an hommage, albeit with time travel thrown in.

Doctorow is reliably good at explaining things, and sections read like breezy DIY tutorials. (“Knowing how to turn a toilet paper roll and three bucks’ worth of parts into a camera-detector is just good sense.”) But he’s also terrific at finding the human aura shimmering around technology. I like his description of a blogger “sniping out the interesting stories and throwing them online” like a “short-order cook turning around breakfast orders.” He’s sharp about how old paradigms seem to deliberately misunderstand emerging ones, such as when, at the height of his notoriety, M1k3y holds an international press conference in a Second Life-like environment, a pirate-themed game world called Clockwork Plunder. By the time the next day’s official news has come out, his nuanced answers get bulldozed into one-sided provocations.

My favorite part of “Little Brother” might seem slight, little more than a flourish: At one point it is necessary that someone’s purloined cellphone remains open in order for certain crucial data not to be lost, draining the battery. He finds an appropriate charger to maintain the level, and when he passes it onto a friend, he tells her, “You need to keep it from going to sleep.” Not just any techie can make the light of a cellphone seem so fragile and poignant

*

Ed Park is an editor of the Believer and the author of the forthcoming novel “Personal Days.” His column Astral Weeks appears monthly.

More to Read

Sign up for our L.A. Times Plants newsletter

At the start of each month, get a roundup of upcoming plant-related activities and events in Southern California, along with links to tips and articles you may have missed.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.