Sauvignon Republic: a Sauvignon Blanc specialist

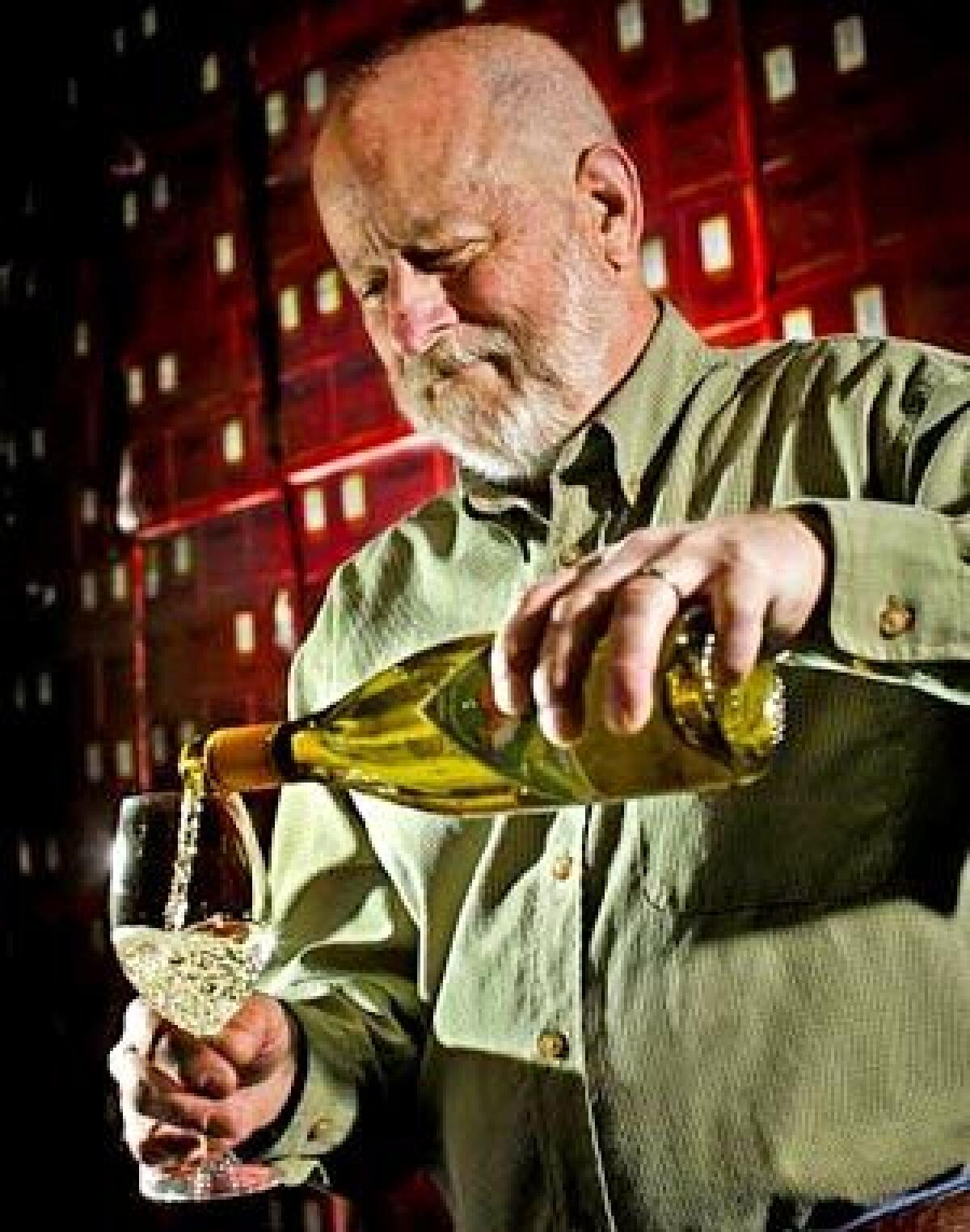

AS HE stands before his Sensory Evaluation of Wine class at UC Davis Extension, John Buechsenstein, winemaker, professor and commercial vineyard location scout, sticks his nose into the tilted wine glass and breathes in deeply. Ah, Sauvignon Blanc: the chameleon of the wine world.

Buechsenstein’s nose knows. As an instructor at Davis and at the Culinary Institute of America at Greystone in St. Helena, Buechsenstein teaches students how to sniff out wine’s variations. Sauvignon Blanc, he says, is an underrated star that can display multiple personalities.

As an entrepreneur and partner in the company Sauvignon Republic, he’s developing -- under one label -- a number of different Sauvignon Blanc wines made in select locations all over the world. Over several years, he hopes not only to produce exemplary Sauvignon Blancs but also to illuminate the site-sensitive wine characteristic known as terroir.

Buechsenstein describes his job as being “the boots on the ground” around the world, scouting locations and making the wine. The first Sauvignon Republic release, in 2003, was from the Russian River. A wine from Marlborough, New Zealand, was added to the portfolio in 2004, and a Stellenbosch, South Africa, Sauvignon Blanc joined the lineup in 2005. With the 2007 vintage released this month, the company adds a Potter Valley wine from Mendocino. All of the wines have a suggested retail price of $18.

Sauvignon Blanc, Buechsenstein says, picks up characteristics of the climate and soil where it is grown; its aromas and flavors are altered by that place. The heady green-grass perfume of a typical New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc, for example, contrasts sharply with the sweet pineapple and stone fruitevident in a Russian River Valley Sauvignon Blanc.

So true, says Fred Brander, owner and winemaker at Brander Vineyard, one of California’s most acclaimed Sauvignon Blanc producers. After 31 years of experience growing the grape in the Santa Ynez Valley, he says, “This grape shows terroir to an extent that you don’t see in other white wine grapes.”

Minimalism rewarded

THE PROBLEM with Sauvignon Blanc, says wine director Pieter Verheyde of Bastide restaurant in West Hollywood, is that it adapts a little too easily to wherever it is planted. In uninteresting places, the easy-to-grow grape produces a “boring” wine, which accounts for the proliferation of bland Sauvignon Blanc wines not only from California but from many New World wine regions.

For the mass market, the wine is easily manipulated in the winery. That’s the story behind Robert Mondavi’s Fumé Blanc, an oak barrel-aged Sauvignon Blanc the master marketer created in the 1960s. Its nickname: Poor Man’s Chardonnay.

When Sauvignon Blanc is planted in the cool climates, picked at the proper ripeness and fermented in stainless steel, Verheyde says, it struts its stuff.

Buechsenstein agrees. And that minimalist approach to making Sauvignon Blanc is the common vision of the Sauvignon Republic partners, who, with Buechsenstein, also include former Fetzer Vineyards President Paul Dolan, sales and marketing manager Tom Meyer and food and wine education director John Ash. The wine concern plans to produce 100% Sauvignon Blanc wines in a dozen places around the world. The collection will showcase “a clear fruit-forward expression of each region,” Buechsenstein says.

The partners plan to expand the company’s catalog with a new wine each year. Next after the Mendocino release is a Sauvignon Blanc from Friuli, Italy. There are plans for wines from Chile’s Casablanca Valley, Australia’s Tasmania and Adelaide Hills regions, Slovenia, Austria, and even Uruguay. Of course, the most famous Sauvignon Blanc regions in the world -- the Sancerre region in France’s Loire Valley and Bordeaux, most likely Entre-Deux-Mers -- are on the list as well.

Regional influences

THAT’S asking a lot of one grape, and of Buechsenstein. For each new wine, he pulls together a local winemaking team, contracts with growers willing to farm and harvest grapes to his specifications, rents space in a contract winery and trains his winemakers to stick to a stainless-steel fermentation and no oak influence protocol.

“It’s been a tough learning curve. I can’t be in all of these places all of the time, so I have to have good relationships with people who know what we want,” he says. “I thought we would have more countries by now, but it’s been hard to put these wines together.”

Buechsenstein’s winemaking approach is in line with tradition in the grape’s home in Sancerre in the Loire Valley of France. Warm summers and cold continental winters there produce a Sauvignon Blanc with bright herbal aromas, crisp natural acidity and pleasing mineral flavors that mirror the limestone soils in the rocky hillside vineyards.

In Friuli-Venezia Giulia, the far northeast corner of Italy with a maritime influence, the same approach produces Sauvignon Blanc with grassy, herbal flavors akin to Sancerre. But the region also is known for more exotic wines with peach and stone fruit aromas and flavors, according to Joe Bastianich and David Lynch’s guide “Vino Italiano: The Regional Wines of Italy.”

Popular Bordeaux blanc wines, such as Pessac-Léognan and Graves, typically are blends of Sauvignon Blanc and Sémillon aged in oak barrels. But in Entre-Deux-Mers, there are wines made with 100% Sauvignon Blanc that aren’t influenced by oak flavor.

The Sauvignon Republic project starts to seem more gimmick than grand vision when it comes to the long list of New World regions. Chile’s Casablanca Valley isn’t known for any particular style of Sauvignon Blanc, nor is Tasmania. They’re just cool-climate regions that should produce tasty white wines.

Some of Sauvignon Republic’s wines will be more traditional than others, Buechsenstein agrees, and future pricing will reflect the variations in costs of production. “It’s a treasure hunt,” he says.

The challenge everywhere with Sauvignon Blanc is its unusual vigor. If the canopy is allowed to grow out of control, he says, Sauvignon Blanc’s signature herbal aromas and flavors turn rank and the wine tastes like asparagus. Trim the canopy too much and expose the grapes to direct sun, and they turn golden. The wine loses its natural acidity and is often flabby and bland.

Controlling what happens in the vineyard is the key to a great Sauvignon Blanc, says Mia Klein, who makes Hyde Vineyard Carneros Sauvignon Blanc under her Selene label. A fan of the grape, she considered making it in several different places in California. Ultimately, she decided that controlling the farming and harvesting of such a sensitive grape in one place was challenge enough.

Then there is the problem with consumer perception. Because Sauvignon Blanc can be so many different things, “people don’t know what to expect when they buy it,” Klein says. Consumers are reluctant to pay a premium for the wines, and that makes growers reluctant to invest in the vineyards. The result has been too many uninteresting, monochromatic wines.

Different signatures

SO FAR, Sauvignon Republic has produced four appealing wines that are distinct from one another but share a bracing acidity and bright fruit flavors.

Sweet floral aromas and grapefruit flavors are the signature of the 2007 Potter Valley wine from Mendocino County. The 2006 Russian River wine offers pineapple aromas and flavors. Green grass aromas with ripe herbal flavors characterize the 2006 Marlborough wine. And the most unusual of the four Sauvignon Blanc wines is from Stellenbosch. It’s a complex wine with a bitter wood taste and mineral bite on the finish.

Although critics have lauded the individual wines, the partners plan to maintain limited production levels of no more than 8,000 cases a year of each wine.

Wouldn’t an internationally sourced collection of Chardonnay wines produce as varied a selection? Verheyde says it would. And Riesling is renowned for producing wines with dramatic variations depending on where the grape is grown.

But nothing is as expressive as Sauvignon Blanc, Buechsenstein says.

Every student who attends one of his classes, he says, comes eager to learn why wines smell and taste the way they do. He hopes the Sauvignon Republic collection will be his best teaching tool.

More to Read

Sign up for our L.A. Times Plants newsletter

At the start of each month, get a roundup of upcoming plant-related activities and events in Southern California, along with links to tips and articles you may have missed.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.