Parting the waters of what once was

Yosemite’s Hetch Hetchy Valley has legendary status in California for being the most beautiful glacier-carved gash in the Sierra you’ll never see. Its death by damming in the 1910s is said to have hastened the death of John Muir, who vigorously fought for its preservation. Today, lying beneath 117 billion gallons of water behind the O’Shaughnessy Dam, the beauty of the Hetch Hetchy Valley is a dream that resurfaces only now and then from beneath 300 feet of pristine Sierra snowmelt.

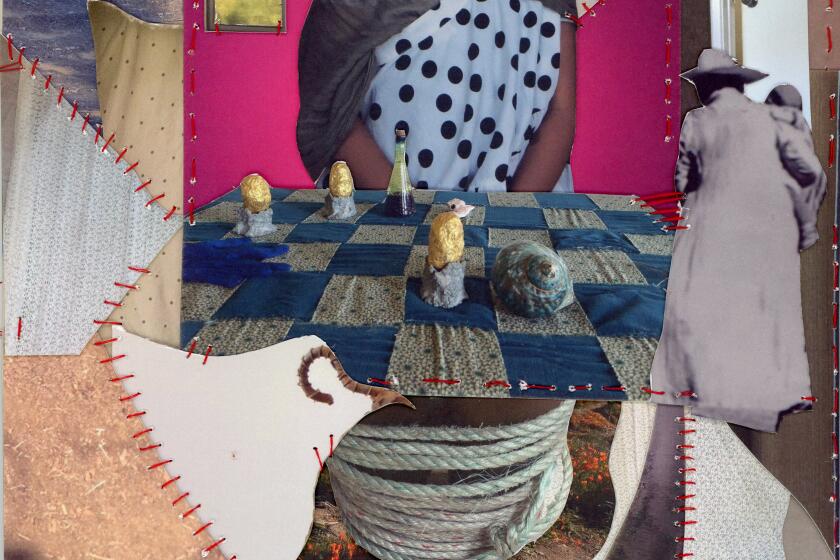

Last fall, the Oakland office of the national nonprofit Environmental Defense organization published a provocative study calling for the restoration of the Hetch Hetchy Valley, and as powerful as the arguments are, it is hard not to linger over the image on the cover of the report.

Springtime in Yosemite never seemed more inviting. Here, thanks to digital composite imagery, was the Tuolumne River once again: a cobalt strip winding among fields of goldenrod, tall pines lanced against cliffs, a distant waterfall cascading down granite and Kolana Rock, front and center. Muir would be proud.

Then we woke up: Dams don’t get torn down. Sure, there are a few exceptions, but Hetch Hetchy is on a scale all its own. We might as well throw our hopes at Glen Canyon. No matter how persuasive and substantiated, Environmental Defense’s proposal (see https://www.environmentaldefense.org ) seems like wishful thinking, an elegant parlor game of What If.

Yet still.

What if the O’Shaughnessy Dam did not exist? What would the Hetch Hetchy Valley be like? We decided to craft an assignment to answer this question, and the result is the short story by novelist Greg Sarris, a work of fiction informed by historical fact, which we publish today.

Literalists may find our approach too frivolous, too speculative. Yet to deny the value of wondering is to deny the role the imagination — and art — have played in shaping the experience of the West. Consider this: If the dream at the turn of the 20th century was to rebuild a magnificent city, San Francisco after the earthquake, why can’t we dream today about rebuilding a valley?

And not just any valley.

Hetch Hetchy is most famously Yosemite’s twin, and no landmark in California has greater symbolic value than Yosemite. After 1856, when journalist, hotel keeper and Englishman James Mason Hutchings began publishing a magazine with stories and illustrations of the valley, this singular natural resource quickly became part of our national heritage.

Burying its twin in water — and depriving the world of the valley views of Kolana and the waterfalls of Wapama and Tueeulala — was to deliver a stunning pronouncement on that heritage.

No wonder Muir, who saw nothing less than the Sacred in these mountains, described the forces marshaled against him in his decade-long fight to save the valley as “Satan and Company.” “These temple destroyers,” he wrote, “devotees of ravaging commercialism, seem to have a perfect contempt for Nature, and instead of lifting their eyes to the God of the mountains, left them to the Almighty Dollar .”

Submerged, Hetch Hetchy is not only an object lesson but also an aesthetic challenge. How do we see what we will never see?

There is a lesson here in the past. More than a century ago, artists converged beneath Half Dome and Bridalveil Falls to capture the mystical interplay of storms and moonlight, granite and meadows. The writings of Muir, the plates of photographer Eadweard Muybridge and the canvases of painters like Thomas Ayers, William Keith, Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Hill provided an aesthetic experience for people who would never stand upon these rocks or beneath these trees.

Today if we acknowledge that Ansel Adams found in black-and-white photography a medium best suited for capturing the faces of Yosemite Valley, then what medium do we use for the lost forests and meadows of Hetch Hetchy? If composite digital imaging is effective, then a short story might be, as well.

There is, after all, something of a tradition in this. Ursula K. Le Guin considered the Hetch Hetchy Valley in a short story, “A Hole in the Air.” Here a man from “the Range of Light” finds himself living far from home with a strange tribe, backward-head people who are deaf and who have electrical wires in their ears. They smoke continuously and make war. The man tries to get home — to his pole-house — and when he succeeds, he discovers that his home is gone. “The backward-head people had dammed Pass River at the narrow part of the canyon. It was all under water in Pass Valley. The trees and rocks were under the water .”

(Such imaginings are relevant when we consider the debate currently focused on the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, a track of land situated on Alaska’s North Slope that for its remoteness is almost invisible.)

With Environmental Defense’s Hetch Hetchy proposal, we face a greater challenge than the one that Congress voted upon when it approved the dam in 1913. We are asked to imagine what once was.

Visit Hetch Hetchy today in either a digital image or in an imaginative story, and you inevitably experience a sense of loss and wonder, of curiosity and frustration. Here are the contradictory impulses — to save and to destroy — that nature too often seems to inspire: our Promethean aspirations, our shame and the relative wisdom of our decisions.

As naturalist Verna Johnston writes in her book about the Sierra Nevada, “Today’s human demands for Yosemite Valley point up that earlier choice to inundate Hetch Hetchy as an action against the long-term national interest . Now underneath a hundred billion gallons of water, Hetch Hetchy over the years could have brought outdoor pleasure to millions of people.”

Understanding the value of that lost pleasure — and as Le Guin and Sarris suggest — is the challenge that lies ahead of us.

Thomas Curwen is the editor of Outdoors. He can be reached at thomas.curwen@latimes.com.

More to Read

Sign up for our L.A. Times Plants newsletter

At the start of each month, get a roundup of upcoming plant-related activities and events in Southern California, along with links to tips and articles you may have missed.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.