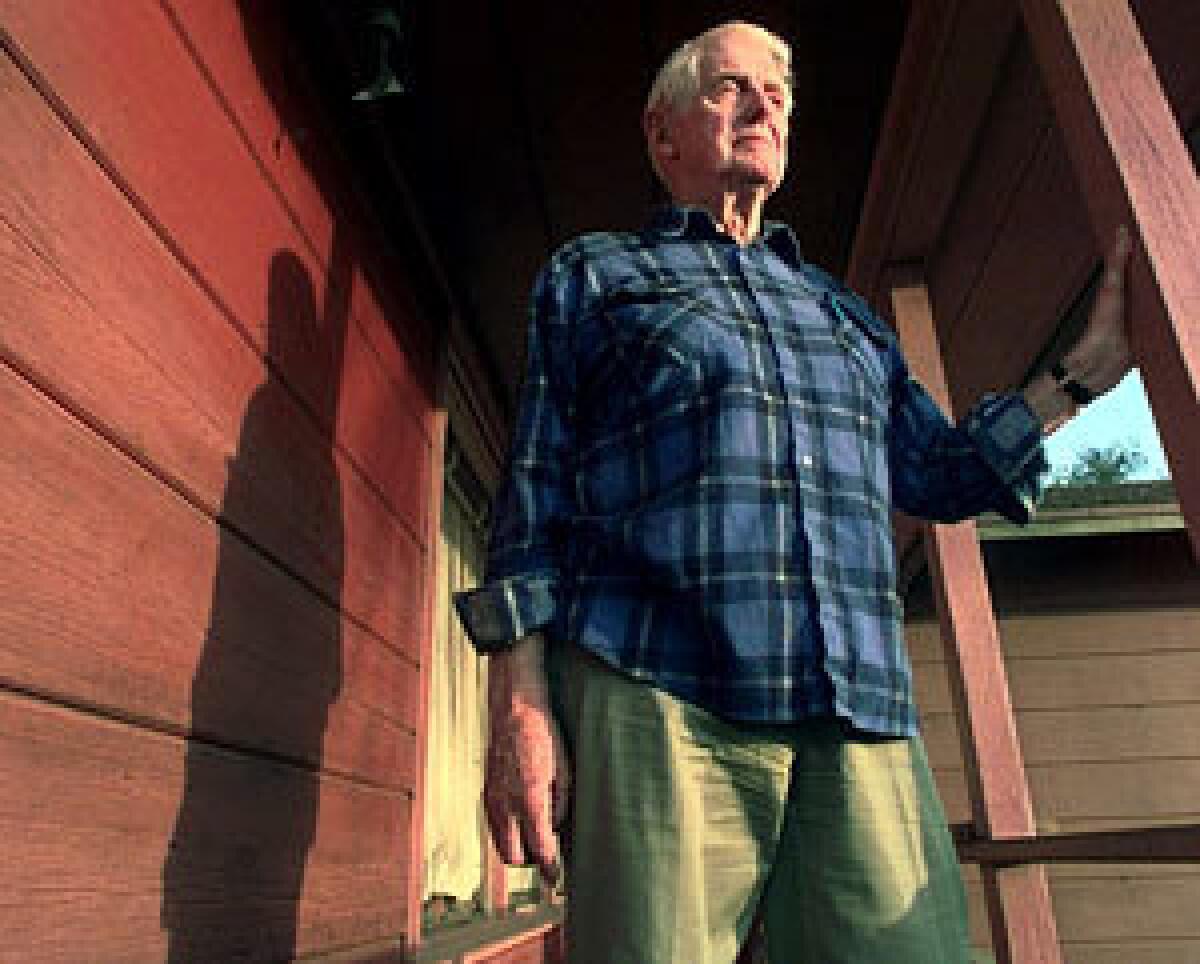

David Brower, crusader for the environment, dies at 88

David Brower, an oracle for wilderness and the most indomitable environmental warrior of 20th century America, has died. He was 88.

Brower, who died of bladder cancer Sunday at his home in Berkeley, was a combative, prickly, inspirational and visionary figure who led the transformation of an easygoing culture of nature lovers into a hardened army of nature defenders.

Among his achievements, Brower spearheaded the fight to save the Grand Canyon from dams. He also organized successful opposition to dams that would have flooded Dinosaur National Monument--although paying a price he would always regret: acquiescing to Glen Canyon Dam on the Colorado River, above the Grand Canyon.

Brower, with flyaway hair and piercing blue eyes, sounded the rallying cry for Redwood National Park and Point Reyes National Seashore, among others. He was influential in making nuclear power an issue for environmentalists, and he was among the first to insist that the environment was a matter of global concern.

He instituted the publication of the large-format books and full-page advocacy advertisements in newspapers that are commonplace today as a means of driving home warnings of the threats to wild places. In countless other fights, right down to preservation of community gardens in big cities, Brower’s influence altered the landscape and the values of contemporary America.

He became the first executive director of the Sierra Club, remaking a quiet organization of hikers and picnickers into the nation’s leading conservationist organization. Later, he founded Friends of the Earth, a more pugnacious group. In both instances, his fiery temperament and audacity ultimately led to his estrangement from those organizations, but did little to diminish his reputation.

“Judged by his life and his career, he was, in his time, the soul of the movement to save the Earth. He became its flag bearer,” said Martin Litton, a fellow crusader for more than five decades. “More than anyone else, including John Muir, he endowed the Sierra Club with greatness. Dave lived in a time when you couldn’t just rhapsodize about nature. You had to be hardheaded about it, and he was.”

Denis Hays, international chairman of Earth Day, called Brower “the gold standard by which many leaders of the environmental movement judged themselves, and usually came up short.”

One of Four Towering Figures

In 20th century America, four towering figures shaped what is now regarded as environmentalism: the trailblazer John Muir, who died in 1914; the writer Rachel Carson, who forced the country to fathom the dangers of industrial pollution; the philosopher Aldo Leopold, who championed wilderness and popularized the science of ecology; and the activist Brower.

He came to prominence 50 years ago, just as America’s mood about the outdoors was ready to shift. Ingrained ideas about reclamation and gentleman conservationists were yielding to concerns about ecosystems, about the impact of industrialization, about sustainability and human responsibilities to nature. In a simplified sense, as the ideas of Muir, Carson and Leopold ripened, Brower undertook the harvest.

He was a tireless crusader who recruited untold thousands of converts to the cause. Hardly anyone with a position of influence in the environmental movement today was untouched by his passion.

Basically shy, sometimes aloof, frequently arrogant, Brower would loosen up in the outdoors with his engraved Sierra Club steel cup in his hand and the sound of wind in the trees, or likewise at his favorite watering holes with a Tanqueray martini before him. For a while, ground zero for his work was a neighborhood hangout, Enrico’s Sidewalk Cafe in San Francisco’s North Beach, where Brower held court in his own booth, complete with private telephone.

In his book “Let the Mountains Talk, Let the Rivers Run,” Brower told how he wanted to be remembered, and summed up his conservation philosophy. At the time, he was in the nation’s capital, and a fellow environmentalist had asked him the source of the quotation, “We do not inherit the Earth from our fathers, we are borrowing it from our children.”

“I have no idea,” Brower replied.

Why, said the friend, those words are chiseled in stone at the National Aquarium in Washington “and your name is underneath them.”

Brower was pleased but puzzled. “At home in California, I searched my unorganized files to find out when I could have said those words. I stumbled upon the answer in the pages of an interview that had taken place in a North Carolina bar so noisy I could only marvel that I was heard at all. Possibly, I didn’t remember saying it because by then they had me on my third martini.”

Brower continued: “I decided the words were too conservative for me. We’re not borrowing from our children, we’re stealing from them--and it’s not even considered to be a crime.

“Let that be my epitaph, when I need it.”

Born in Berkeley on July 1, 1912, Brower made his first trip to Yosemite when he was 6. It remained, always, his favorite place. His mother, an avid hiker, lost her sight when he was 8, and he became her guide in the outdoors, learning the words to convey the majesty and emotion of the wild.

Brower attended UC Berkeley and worked as an editor at the university press. He took to the mountains with zeal. He was a climber when climbing was still young on the West Coast. He chalked up the first ascent of New Mexico’s Shiprock. He joined the Sierra Club in 1933 and, overcoming his fear of crowds, became a leader in the club’s outings program.

In 1935, he went to work for the Curry Co. concessionaire at Yosemite and rose to be publicity manager. In a sweet irony, he learned to turn the mountains into promotional films--a skill he would effectively use against those who would develop or exploit wilderness.

Beginning the pattern, he was fired. He undertook his first conservation campaign in 1939, riding the lecture circuit throughout California with a silent movie about the high Sierra. He brought a phonograph and played emotional music and narrated the film with his powerful voice, arguing for what would become Kings Canyon National Park.

Brower served with the 10th Mountain Division in Europe in World War II and was awarded the Bronze Star. He returned as editor of the Sierra Club magazine and launched the club into publication of coffee table books, beginning with one by his friend, the photographer Ansel Adams.

With a $10,000 veteran’s loan, he constructed a modest house on Grizzly Peak in Berkeley, where he had first roamed the outdoors. Cluttered with books and papers and mounting piles of memorabilia, it remained his home thereafter.

As the land around him filled in with subdivisions, Brower began to wish there could be an open hunting season on developers. Not to shoot them, he explained, “just tranquilize them.”

Fight With IRS Over Grand Canyon

Under his leadership as executive director from 1952 to 1969, the Sierra Club grew from 2,000 hikers to 78,000 true believers. In what was perhaps the most important confrontation of his life, he propelled the organization into a fight against damming the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon in 1966. The Internal Revenue Service responded by revoking the Sierra Club’s nonprofit tax status--which Brower leveraged into a wave of public sympathy.

“Backlash from the IRS intervention was probably one of the important factors in staving off the dams,” he wrote in his 1990 memoir “For Earth’s Sake.”

Writer John McPhee, in a classic book-length profile, called Brower the Sierra Club’s “preeminent fang.”

Russell Train, then chairman of the Council on Environmental Quality in the administration of President Richard Nixon, remarked: “Thank God for David Brower, he makes it so easy for the rest of us to appear reasonable.”

If all great lives have a moment of remorse, Brower’s was a doozy. It occurred a decade earlier in the same web of Southwestern rivers that feed into the Grand Canyon.

Most of America then had its mind on boom times and creature comforts. But Brower saw the price of progress. He roused opposition to proposed dams on the Yampa and Green rivers, which would have flooded Dinosaur National Monument. In 1956, he and the Sierra Club won. The Sierra Club board, meanwhile, agreed to withdraw opposition to a string of other dams in the Southwest--among them, Flaming Gorge on the Green River and Glen Canyon on the Colorado.

The Sierra Club had upheld the maxim that wild lands administered by the National Park Service should not be flooded. Glen Canyon had no such designation and was barely known among conservationists. Brower did not challenge the board.

He never forgave himself. He called Lake Powell, which was created by the damming, a blasphemy. Later in life, he championed the cause of draining it.

“I asked Dave Brower why he just sat, and have continued to ask him,” said Brower, in a third-person conversation with himself. “He has no answer.”

Fired as leader of the Sierra Club in a wrenching battle, Brower founded Friends of the Earth in 1969. Echoing his critics, he said the new organization was intended to “make the Sierra Club appear reasonable.”

Eventually, he had another stormy parting. And in 1982, he established the San Francisco-based Earth Island Institute, where he remained as chairman until his death.

Although a man of towering self-regard, Brower also had a woodsman’s awareness of things happening around him. He listened carefully, even when he did not seem to. Thus, his ideas, his supply of causes and his circle of acquaintances remained fresh through more than half a century of advocacy.

Former Interior Secretary Stuart Udall once called him “the most effective single person on the cutting edge of conservation in this country.”

Historian Roderick Nash, author of “Wilderness and the American Mind,” chose his words carefully as he called Brower the 20th century’s “foremost force in translating the public interest in parks and wilderness into action.

“He left the environmental cause different and far stronger than when he found it. Anyone concerned with parks, with wilderness, with the health of the Earth, stands in his debt.”

Brower is survived by his wife, Anne, and four children, Kenneth, Bob, Barbara and John.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.