On faith’s path: In Italy displays of devotion inspire hope in an imperfect world

On our fifth day in Rome, we went to see the pope. St. Peter’s Square buzzed with anticipation. The line for security screening stretched along Bernini’s colonnade, and tourists and pilgrims, once scanned and searched, hurried for the best of the folding seats.

My wife, Margie, and I were drawn to the celebrity of this man whose pronouncements seem to have silenced many critics of the church, and after a full slate of cathedrals and ruins, museums and late-night wanderings for gelato, we wanted to catch this spectacle, his weekly audience, before continuing to our other destinations.

------------

FOR THE RECORD:

Scrovegni Chapel: In the Dec. 20 Travel section, a photo of the Scrovegni Chapel accompanying an article about displays of devotion in Italy was credited to Piero M. Bianchi. The photographer was Gabrio Tomelleri / Archivio Fotografico Padova Terme Euganee Convention & Visitors Bureau. —

------------

I am not a religious man. The Christian faith, though well-placed in my family tree, eluded me. No priest will be found in my childhood, no memories of devotion, Catholic or otherwise, and the stories of the New and Old Testament have more of an aesthetic than spiritual pull on me.

The sun shone brightly on the basilica’s façade. Cumulus clouds rose overhead like a trompe l’oeil. The air smelled of sunscreen; selfie sticks poked above a sea of hats and parasols. Men in dark suits stood before an outdoor stage with a sun shade, and Swiss Guard, cartoonish in their livery, kept their distance.

Atheist, agnostic, secular humanist, I avoid labels lest they rule out the possibility of something new. Truth is, I am a little of each, sensitive to the meaning of these sacred spaces and practices that bring hope to a world as imperfect as ours.

A charge rippled through the crowd when Pope Francis made his entrance, his white skullcap breezing above the gathering. From the back of what seemed to be a golf cart, he waved to his fans as they pushed against the barriers, drawn to the blessing of his raised right hand.

Today’s homily

After a few circuits, he stepped on stage and eventually to an open microphone. A breeze lifted the collar of his cape. He spoke first in Italian, then in English.

“Death,” he said, “is an experience which touches all families, without exception.”

I was a little stunned. This hardly seemed a topic for such a happy summer morning, and the more he spoke, the more I realized how little I knew about the consolation of faith, the point of his homily.

Afterward, the crowd dispersed, and we caught the afternoon train to Naples, the second of our five stops in Italy.

Little did we know that the words spoken this morning would follow us for the next two weeks. We would hear them again and again, spoken in small eccentric statements, in intimate expression and in grand vistas that looked over the expanse of time.

“Faith protects us from the nihilistic vision of death,” the pope had said, and in the end, I think I understood.

Naples: Christmas Alley

The Spaccanapoli is best described as a slot canyon through the heart of Naples. Four-and five-story apartments rise up from this narrow cobbled strip, crowded with shops and pedestrians. Where others might find pickpockets and purse snatchers, we found a surprising conviviality.

Via San Gregorio Armeno is a narrow street in Naples, Italy, often called Christmas Alley.

We had hired a guide, Antonella Rizzo, who was eager to show us her beloved city, and as we wandered through this ancient center, pausing to watch a special delivery (a basket lowered and raised from an upper apartment) and sample a frittatina (fried pasta with eggs), we came to Christmas Alley, Via San Gregorio Armeno, and felt as if we had entered Lilliput.

Hundreds of figurines crowded street stalls and shop windows: angels and elephants, Lady Gaga and Pope Francis, soccer players and politicians. Sides of ham and loaves of bread, no bigger than jelly beans, had been stacked in open displays. Empty villages sat in miniature ruin.

In the midst of this fantastic promenade were dozens of Marys and Josephs, Wise Men in varying states of adoration and baby Jesuses sleeping, gesturing, smiling or swaddled, ready for any open manger.

Antonella took us into one shop, where nativity scenes — known as presepi — had been arranged, each character hitting his mark. Some scenes stood under bell jars, some in the open air, each elaborately detailed and densely populated.

In the workshop upstairs, owner Marco Ferrigno greeted us. He said he had entered the business reluctantly, having studied economics and intending to become an accountant. But his father was more persuasive, and he found his place in a family tradition dating to 1836, crafting these figurines.

Christmas in Naples, Antonella explained, is incomplete without the presepi, talismans of hope for families in the coming year. Created from terra cotta, wood, cork and silk, the characters — and their accessories — keep bad luck at bay.

An umbrella pierces the evil eye. Fowl promises fertility. Scissors sever gossip, and a broom sweeps away evil. A surfeit of bread, fish and cured meats exorcise the threat of poverty.

Among the stock characters are Ciccibacco the drunk, Carmela with her breads, Pulcinella from commedia dell’arte, and one man, Benino, always asleep amid the commotion. His sleep, we were told, allows for the presepi to exist. The world we see is his dream, for a world without want can only be a dream.

As we departed, we paused in front of the scenes downstairs, which suddenly made sense. In the midst of ordinary life lay the possibility of the divine. Superstition may be another word for faith, but that hardly matters.

Padua: Giotto’s chapel

The cicadas hummed as Margie and I waited in the garden outside the Cappella degli Scrovegni in Padua for our reservation.

Seven centuries of wars, earthquakes and the demolition of adjacent buildings could not bring down this chapel raised between 1303 and 1305. It now stands alone in a modern garden set with abstract art and ancient statues.

We were ushered into a small waiting room, where we breathed filtered air and waited until the temperatures stabilized. Such is the fragility of the world we were about to enter, and when we stepped inside the chapel, little could have prepared us for what we saw.

We knew about Giotto, the creator of this space. Seven centuries ago he had laid out in nearly 40 frescoes a narrative more ambitious that anything the Western world had seen. In the beginning was the word, as we are told, but he gave it an image.

The crowds at the temple. Flames rising from a sacrifice. The waters of the Jordan River. A fat man sampling the wine at Canaan. The devil consorting with Judas. Christ’s execution and ascension.

The colors, the perspectives, the outstretched arms and worried brows pulled on us clamorously. We found ourselves crossing the chapel from one side to the other, eyes scanning from top to bottom, amazed by the cinematic complexity of each scene.

Slowly the sequence of the pictures, like the frames of a movie, fell into place, and the intensity of the drama was softened by the lapis blue of the ceiling and in the sky of the frescoes that surrounded us.

Visitors are allowed only 20 minutes in the chapel — with the chapel accommodating only 25 visitors per visit — and we had booked back-to-back sessions to give us time to make sense of all that we saw.

Of course, we had heard the stories. We knew how they began and how they ended, the lessons for our lives, but under Giotto’s hand, the familiar had become strange again, strange for becoming so real.

No image left us more moved than the encounter between Judas and Christ. Nose to nose, they stare into each other’s eyes, calm and penetrating gazes whose intimacy only heightens the betrayal. Soldiers, all steely-eyed men, rush in, as one apostle, Peter, tries to defend his friend.

Back in the garden, cicadas humming in our ears, we sat on a stone wall as if to catch our breath. The world seemed almost inadequate after having been enveloped by Giotto’s celestial blue.

To have faith, he seemed to tell us, is to endure.

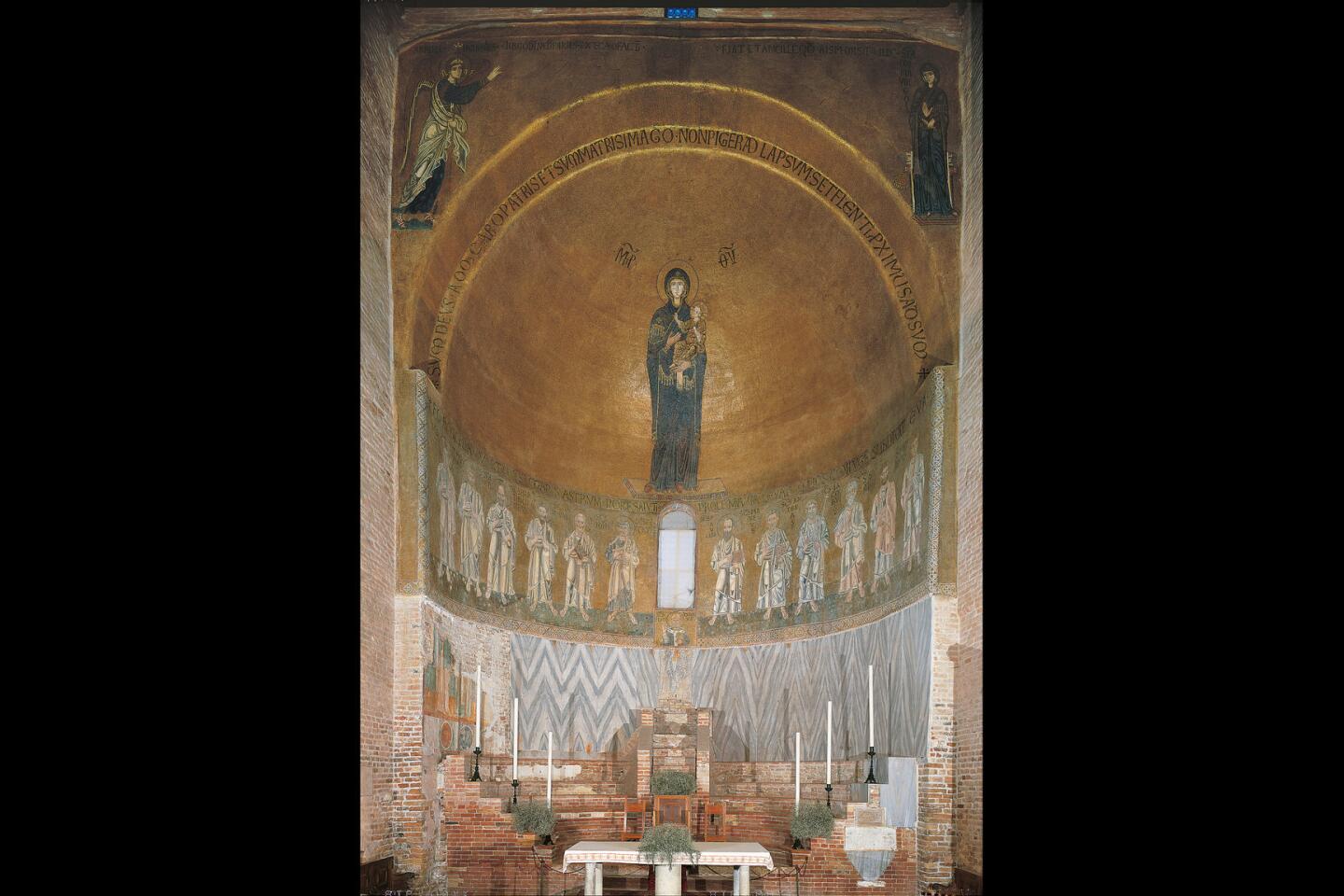

Torcello: mosaic Madonna

With a tear on her cheek, she looked at us from across 1,000 years, this Madonna in blue, surrounded by gold tiles in the apse of the Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta.

After three days of jostling with the crowds of Venice, Margie and I were happy to find ourselves almost alone on the island of Torcello, just an hour away by vaporetto. Greeted by crowing roosters and songbirds, we followed a canal toward the towering campanile, past modest farms, restaurants and a small hotel.

The day was hot and humid, and we were among the first to enter the cool recess of the basilica. The stones, the tiled floor, the first glimpse of this ethereal mosaic straddling Byzantine and Gothic styles, conspired to slow us down and to speak in whispers.

Originally built in the 7th century, the church was enlarged in 1008 when this mosaic was presumably created. Legend has it that the workers were in a hurry, lest the world come to an end before they finished. But I find that hard to believe. Such an image of sweet melancholy could not be rushed.

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

In her wistfulness, I thought I saw an apology for all that had occurred, the centuries of strife and discord — the collapse of an empire, the martyrdom of the saints, the barbarians at the gate — that even the birth of Christ, who in her arms seemed strangely unaware, could not ameliorate.

I imagined that she too could see into the future to where we stood today, but I suppose my impression was colored by the opposite wall, a textbook rendition of the Last Judgment brutal in comparison. Here Christ is all business holding Adam by the wrist, Eve beside him. Below St. Michael holds the scales that weigh each soul.

Stepping outside, we listened to the bells of the campanile strike noon. The courtyard was full of tourists. Postcard and trinket stands had opened, and we wandered to a bistro by the canal for lunch.

We would be flying home in two days, our encounters over with such devotion.

To call faith merely hope seemed too simplistic for all that we had seen during our time in Italy. Whimsical and inspired, didactic and even threatening, faith was the dream of a sleeping man in Naples, Giotto’s inspiration to realize our humanity and a 1,000-year-old perspective on the heartache of time.

Few things are more inspiring than the impulse to believe.

::

THE BEST WAY TO ROME

From LAX, American, Delta, Lufthansa, Air France, KLM, British, Swiss and Aeroflot offer connecting service (change of planes) to Rome. Restricted round-trip fares from $769.

TELEPHONES

To call the numbers below from the U.S., dial 011 (the international dialing code), 39 (country code for Italy) and the local number.

WHERE TO STAY

Albergo Santa Chiara, 21 Via di Santa Chiara, Rome; 06-687-2979, www.albergosantachiara.com/english.Nicely situated a short walk from the Pantheon and the Piazza della Rotonda with its outdoor cafes and gelateria.

Grand Hotel Vesuvio, 45 Via Partenope, Naples; 081-764-0044, www.vesuvio.it/en. A splurge, but worth it to wake up with the Bay of Capri spread before you and Mt. Vesuvius rising to the east.

Locanda Santi Apostoli, 4391A Cannaregio, Venice; 041-099-6916, www.locandasantiapostoli.com.

WHERE TO EAT

Archimede, 63 Piazza dei Caprettari, Navona. 06 6861616 www.zomato.com/roma/ristorante-archimede-navona-pantheon

Schialuppa, Piazzetta Marinari, Naples; 081-764-5333, www.ristorantelascialuppa.net/lascialuppainglese/index.html. Located across the marina from the Hotel Vesuvio in a small neighborhood in the shadow of Castel dell’Ovo, a castle dating back nearly 500 years.

Gran Caffè Gambrinus, 12 Via Chiaia, Naples; 081-41-7582, www.grancaffegambrinus.com/en. Rumored to be the oldest coffee house in Naples. Oscar Wilde stopped in here, as did Mussolini.

Antica Pizzeria e Friggitoria di Matteo, 94 Via dei Tribunali, Naples; 081-455-262, www.pizzeriadimatteo.com

La Lanterna, 39 Piazza dei Signori, Padua; 049-660770, www.lalanternapadova.it/en/. Good for lunch after the Giottos.

Enoteca Ai Artisti, 1169 Fondamenta della Toletta, Venice; 041-523-8944. Amazing seafood and meat with excellent wine pairings, in the fashionable Dorsoduro district.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.