Like it or not, Modernist design has a place here too

The 1945 air bombing of Dresden left many blanks on the map. Several of them in the old town, once sites of Baroque gems, are occupied by replicas of buildings there before the war. Some remain evocative ruins, such as the 1729 Kurlander Palace. Still other empty spaces have been filled with new buildings that make parts of Dresden seem like a miniature Berlin.

Rebuilding in the Modern style and even conserving notable 20th century buildings that survived the war have been difficult for a city that sees itself as quintessentially Baroque. Partly Modernist development plans for the historic square fronting the Frauenkirche, offered by the Italian firm of Arturo Prisco, have been widely debated.

Many Dresdeners are ambivalent about their Soviet-era architectural heritage, epitomized by the 1969 Palace of Culture, home of the Dresden Philharmonic and directly facing the 18th century Frauenkirche. To them, the stark, blockish building with a roof that looks as though it’s erupting and a tile mural depicting “The Victory of the Red Flag” is a particular sore. Until an interest in the Cold War Soviet style is rekindled, work on the building will be limited to acoustical refinements.

Prager Street, connecting the old town to the main railway station, engenders a similar ambivalence. It was rebuilt in the ‘60s to give the city a modern Soviet air. At its southern terminus, the early 20th century train station, or Hauptbahnhof, has been luckier. It is being given a fabric roof and other high-tech improvements designed by British architect Norman Foster.

For lovers of Modern architecture, Dresden has other notable sights to see. Among these are the Hygiene Museum built in the Bauhaus ‘30s in Grosser Garten, the sprawling public park southeast of the old town, and the funky free-form 21st century Art Passage in Neustadt, north of the Elbe River, where Dresden hipsters go for cheap ethnic food.

The city’s contemporary jewel is the 2001 Transparent Factory on the north side of the Grosser Garten, where Volkswagen makes its premium-class Phaeton limousines with 18-way adjustable seats and walnut and chestnut paneling. Volkswagen is so sure of its workmanship that it displays the building of Phaetons behind glass, by men in white suits, on a hospital-clean wood floor.

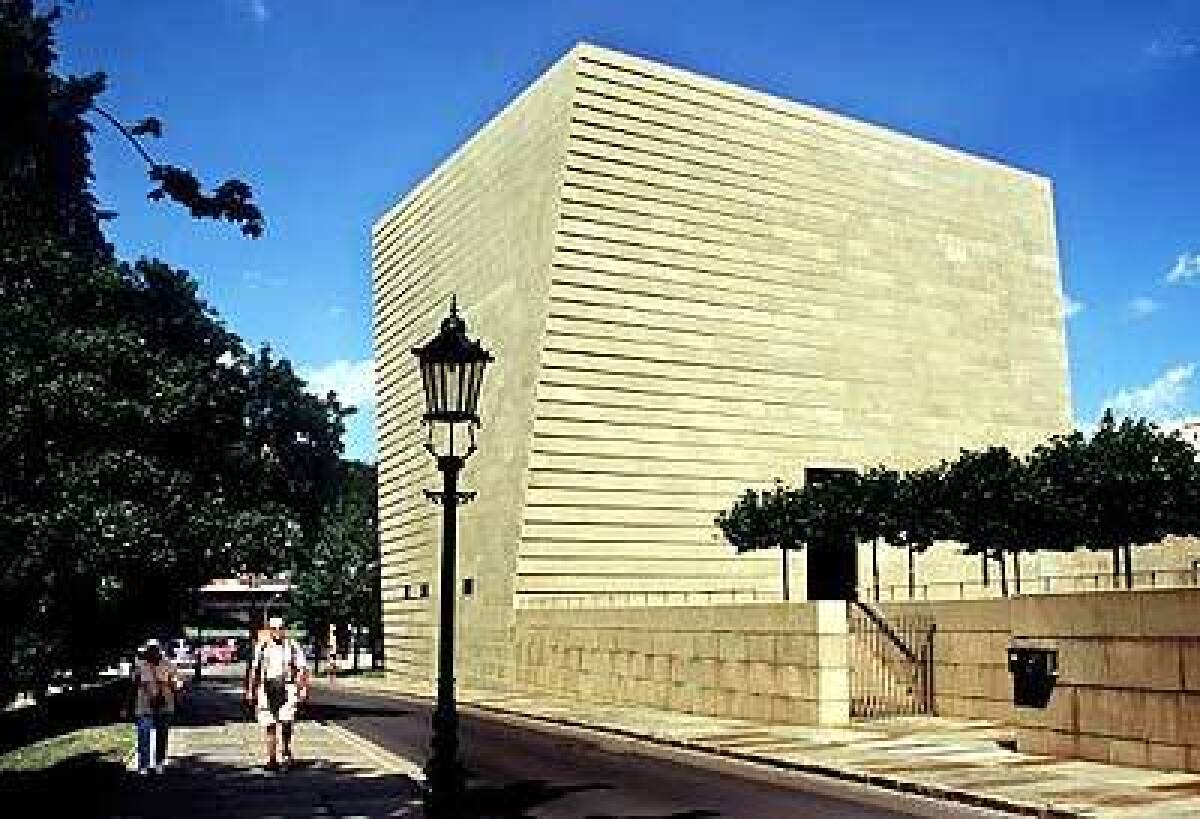

I was differently impressed by Dresden’s New Synagogue, a pair of virtually windowless sandstone cubes connected by a courtyard, on the east side of the old town near the Elbe River. This was because of its history, not its striking Modern architecture. The city’s first synagogue — designed in 1840 by Gottfried Semper, the maestro of the Dresden opera house — was burned on Kristallnacht, Nov. 9, 1938. On that Night of Broken Glass, anti-Semitic sentiment in Germany came violently to the fore. Nazi brownshirts torched it, then made firefighters stand by as it burned. At the time, about 6,000 Jews lived here. Twelve survived the war.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.