A literary stamp to these three houses

In 1937, poet Edna St. Vincent Millay came close to refusing an honorary degree from New York University when she learned she had been excluded from a reception for male recipients of the doctorate at the Waldorf-Astoria and instead was to have a quiet dinner with the chancellor’s wife.

By that time, Millay had written almost 10 books of poetry, won a Pulitzer Prize and cut herself out of corsets and stays by — as she so famously put it — “burning her candle at both ends” during the Jazz Age.

Millay ultimately accepted the degree, but her objections to gender segregation were later taken up by the feminist movement, which viewed the term “women writers” as derogatory, consigning those so labeled to second-class citizenship.

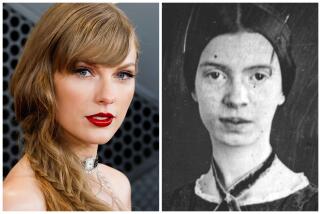

I hope that we’re beyond polemics now and that it is no longer incorrect to think women can’t be great writers. Lately, I’ve been thinking about three who lived near me in the Northeast: Millay (1892-1950), who traded bohemian Greenwich Village for a placid farmhouse in eastern New York state; celebrated novelist Edith Wharton (1862-1937), chatelaine of a mansion across the Berkshire Mountains from Millay in the upper-class summer haven of Lenox, Mass.; and the divine Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), who spent her whole life in Amherst, Mass., and thus “never saw a moor,” though she could conjure up the universe in the space of a single stanza.

I recently toured Millay’s Steepletop, Wharton’s the Mount and the Emily Dickinson Homestead. Seeing the houses in succession gave me a fresh appreciation for their work and the different obstacles they faced to become writers. But perhaps just as significantly, I realized how profoundly at home they were in the beautiful countryside.

Edna St. Vincent Millay

“O world, I cannot hold thee close enough!

Thy winds, thy wide grey skies!

Thy mists, that roll and rise!

Thy woods, this autumn day, that ache and sag

And all but cry with colour! That gaunt crag

To crush! To lift the lean of that black bluff!

World, World, I cannot get thee close enough!”

“God’s World”

Millay was born in Rockland, Maine, and given her unusual middle name because her uncle had once been treated at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Manhattan. Vincent — as almost everyone called her — was the oldest of three daughters raised in a financially strained single-parent family after her ne’er-do-well father was sent packing.

She was 20 when she wrote “Renascence,” a haunting lyric poem about spiritual awakening that made her an overnight sensation. Admirers of the “girl poetess” in 1913 sent her to Vassar, where she made friends, purportedly lesbian; Millay was a lifelong bisexual. After college, she sloughed off her shy provincialism, roaring through the 1920s in Greenwich Village and collecting lovers like bottles of bathtub gin.

In 1923, she married Eugen Boissevain, a Dutch businessman who in many ways was the hero of Millay’s story. He saw her through illness and drug addiction, ran her household and left her free to have affairs — all in order to keep her writing poetry.

Boissevain spotted an ad for a 435-acre dairy farm in the Taconic Mountains near the border of New York and Massachusetts. In 1925, the couple moved to Steepletop, named for a wildflower that grows around the modest white farmhouse on Harvey Mountain. “We’re so excited about it we’re nearly daft in the bean — kidney bean, lima bean, string-bean, butter-bean — you dow whad I bean — ha! ha! ha!” Millay wrote to her mother.

To commemorate the 60th anniversary of the poet’s death last year, the Edna St. Vincent Millay Society opened Steepletop to visitors, who must look sharp while passing through the hamlet of Austerlitz, N.Y., must look sharp for the two-mile gravel road leading up the mountain. The society’s headquarters, a ticket office, bookstore and gallery are in the old garage.

I met Peter Bergman, executive director of the society, who showed me around the house and grounds, left dilapidated when the last resident, Edna’s sister Norma, died in 1986. The gardens that Millay nurtured have gone to seed, though her writer’s cabin, in a grove of pine trees, is intact; the swimming pool where Eugen, Edna and friends disported in the nude is cracked and full of brackish water; and the first floor of the house remains closed because of water damage, except for the slate-floored entry with the poet’s Size 3 boots in the corner.

Millay was petite and redheaded, the perfect flapper, with a low, mellifluous voice that mesmerized audiences when she toured the country giving readings. Bergman showed me her tiny gloves and lingerie, still carefully folded in a bedroom drawer; the monogrammed towels and bidet in her bathroom; her books, daybed and handwritten Silence sign in the library.

After Millay died — as dramatically as she lived — from a fall down the staircase in 1950, Norma left every detail intact, living amid her late sister and brother-in-law’s belongings, hoping someday to turn the house into a museum. The Millay Society now owns the property, relying on donations for upkeep and renovation. As a result, visitors are bound to find Steepletop a work in progress, but singularly authentic. “The house has a life,” Bergman said. “It feels like someone lives here.”

Steepletop, 436 E. Hill Road, Austerlitz, N.Y.; (518) 392-3362, https://www.millay.org. Closed Wednesdays. House tours Fridays-Mondays; garden tours daily, until Oct. 17; $25 for both house and garden, by reservation. The Millay Poetry Trail is open daily.

Edith Wharton

“The terrace at Bellomont on a September afternoon was a spot propitious to sentimental musings, and as Miss Bart stood leaning against the balustrade … the landscape outspread below her seemed an enlargement of her present mood… She found something of herself in its calmness, its breadth, its long free reaches… Was it love, she wondered, or … the spell of the perfect afternoon, the scent of the fading woods, the thought of the dullness she had fled from?”

“The House of Mirth”

It’s thought that Millay and Wharton crossed paths in Paris in the early 1920s, but did not become friends. In fact, it’s hard to imagine two more different women, one a reckless free spirit, the other a society woman raised in the upper echelons of Gilded Age New York and Newport, R.I.

To her mother’s despair, Edith was a bookish little girl; she spoke French, German and Italian and started her first novel when she was 11. Still, she came out at the obligatory debutante ball and was courted by several gentlemen, including Teddy Wharton, whom she married in 1885.

By the time the Whartons moved to Lenox in 1901, Edith had published her first book, “The Decoration of Houses,” co-written with architect Ogden Codman, advocating a departure from the then-popular Victorian style. Plans for the new house, known as the Mount, closely followed the book’s proscriptions, resulting in an elegant white mansion with 35 rooms.

The design of the house was inspired by the couple’s frequent trips to Europe; between 1885 and 1914, they crossed the Atlantic nearly 70 times, prompting Edith’s friend Henry James to call her the “pendulum woman.” In 1903, she set out for Europe again to research a series of articles that became the book “Italian Villas and Their Gardens,” an important source for the Mount’s landscape, including a long, winding drive, formal flower parterres and a cool, green Italian sunken garden.

Edith and a small, select group of friends passed pleasant afternoons alfresco, but mornings were her private time, spent in bed writing compulsively on a lapboard, surrounded by papers and pampered dogs, all miniature breeds such Pomeranians and Skye terriers. They looked on as she completed her first bestselling novel, “The House of Mirth,” in 1905; several dozen more books followed, along with a Pulitzer Prize and the French Legion of Honor.

Her halcyon days at the Mount ended in 1911, when Teddy’s mental health began to deteriorate and she moved permanently to France. After the Whartons’ departure, the estate suffered as it changed hands many times, ending as home to Shakespeare & Company, a Lenox theater company.

In 2001, work to refurbish the Mount began, at a cost of about $15 million.

Executive director Susan Wissler told me more needs to be done, but visitors find the gardens lavishly abloom and the house handsomely restored, with Wharton’s books lining shelves in the first-floor library. Other rooms, such as the dining room and Edith’s suite, were decorated by local designers because the Whartons took their furnishings with them when they moved out.

After my tour, I stayed for a reading of one of Edith’s short stories in the terrace café, one of many events offered at the Mount. “The Mission of Jane,” published in 1904, is about how an adopted daughter brings together a loveless couple by growing up to be such an annoying young woman that her parents can’t wait to get her out of the house when she marries.

Pure Wharton in the perfect setting.

The Mount, 2 Plunkett St., Lenox, Mass.; (413) 551-5107, https://www.edithwharton.org. Open daily May-October; admission $16, plus $2 for docent-led house and garden tours.

Emily Dickinson

“Exultation is the going

Of an inland soul to sea,

Past the houses — past the headlands —

Into deep eternity —

Bred as we, among the mountains,

Can the sailor understand

The divine intoxication

Of the last league out from land?”

“Exultation Is the Going”

Dickinson is my favorite. She studied for a year at my alma mater, Mount Holyoke College, and when my mother died, I found a Dickinson collection with well-loved poems marked, including the one quoted above.

Her celebrity rests on 1,800 poems, left after her death in handwritten booklets, bound with thread from her sewing box and on scraps of paper, used envelopes and chocolate labels. She was too private a person to need the approval of publication and loath to let editors correct her singular, sometimes ungrammatical punctuation, inexact rhymes and jolting meters.

According to the poet’s orders, her younger sister, Lavinia, destroyed her letters when she died in 1886, a disaster for scholars. But Lavinia did set a chain of events in motion that resulted in the publication of the poems. Even so, it took 50 years for the verses to appear unedited, as she wrote them, uncannily modern for their time, admiring critics say.

Others become her devotees because they hear Dickinson’s voice speaking to them intimately about profound matters: life, death, grief, joy and the bumblebee.

Her life was as gloriously strange as her poetry, lived almost from start to finish behind the picket fence and hemlock hedge that bound the Homestead, a fine yellow house on a corner lot down the hill from the center of Amherst. It was constructed in the early 1800s by Emily’s grandfather Samuel Fowler Dickinson, one of the founders of Amherst College; several decades later, her father, Edward, built a grand Italianate mansion next door for her brother, Austin, and his family.

Emily loved Austin and his wife, Susan, the first family of Amherst in the mid-1800s. At the Evergreens, they entertained every passing dignitary, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, though it’s thought that shy Emily stayed home that night. The death of their little son Gib sent Emily into a tailspin of sorrow and ill heath from which she never recovered. Austin later had an extramarital affair with the wife of an Amherst College professor that sundered the Dickinson family, resulting in wars over the dissemination of Emily’s poetry.

Now, her wars are “laid away in books,” as she wrote, and both the Homestead and the Evergreens are again conjoined and open to visitors, thanks to the trustees of Amherst College.Tours underscore the enduring mysteries of Dickinson’s life: the heartbreak that caused her to retire from the outside world when she was in her early 30s; her appearance, recorded by just one remaining daguerreotype; and her illnesses, partly the subject of “Lives Like Loaded Guns,” a recent book by Lyndall Gordon, hypothesizing that she was epileptic.

Much has been written about her. But as Jane Wald, executive director of the Emily Dickinson Museum, told me, “Some things are always going to remain unknowable. It’s the mysteries that keep people interested.”

I began with the audio tour of the grounds, narrated by poet Richard Wilbur who pauses to describe the long gone 11-acre Dickinson meadow across the street where Emily wandered with her big brown Newfoundland, Carlo. Nasturtiums, marigolds and day lilies grow in the garden, her province, together with baking. She refused to touch a duster or broom, leaving the light housework to Lavinia.

Then I toured the houses with a college-aged guide in a white dress — even in her casket, Emily always wore white — who recited poems as we went from room to room in the Evergreens and the Homestead.

Inevitably, the highlight was Emily’s second-floor bedroom, which has her single sleigh bed and a replica of her tiny writing table.

Devotees fall silent or weep to see it, Wald told me.

I thought of my mother, an inland soul gone to sea.

Emily Dickinson Museum, 280 Main St., Amherst, Mass.; (413) 542-8161, https://www.emilydickinsonmuseum.org. Open Wednesdays-Sundays, through December; $10 for house and garden tour.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.