Old Santa Fe: 400 and still evolving

“Oldest house,” panted Robert Chavez, steering his pedicab past a 17th century adobe.

“Oldest church,” he added a moment later, nodding left toward the 17th century San Miguel Mission Church.

Santa Fe — rich, tan, relentlessly artsy and frequently artificial — is really old, by American standards. The city turned 400 this year.

When I visited recently, my mission wasn’t really to chase after old buildings, odd galleries and new restaurants. I wanted a look at Santa Fe’s newest downtown neighborhood, a once-blighted railroad zone whose revival is nearly complete. But in the middle of such history and atmosphere, a tourist gets distracted.

Before long, I was seated in Chavez’s pedicab, hurtling down a historic alley near the ditch that carried the city’s original water supply.

And then I was in front of a jewelry shop on San Francisco Street, where a cowboy guitarist named Wily Jim yodeled like a coyote who’d put in a semester at Juilliard. A few blocks over on Marcy Avenue, the Mira! Boutique was offering a stylish patio chair, crafted in Togo from an old oil barrel — only $250. In the front yard of a gallery on Canyon Road, a woman with a blue scarf daubed white spots on a painting of a dancing pig.

THE BEST WAY TO SANTA FE

From LAX, Southwest and United offer nonstop service, and US Airways, Delta, Frontier, Southwest and United offer connecting service (change of planes) to Albuquerque, which is about 60 miles from Santa Fe. Restricted round-trip fares begin at $218. Since late 2009 American Eagle has been offering one daily nonstop flight between LAX and Santa Fe Municipal Airport. The flight takes about 1 hour and 50 minutes. The jet, an Embraer ERJ-140, seats 44 passengers. Restricted round-trip fares begin at $210.

“I’m just putting dots on her panties while the artist goes and gets a cigarette,” explained Deborah A. Higgs, director of All My Relations gallery. A moment later, artist Robert Anderson returned, took back the brush and regarded the pig anew.

“She represents to me a sort of welcoming, motherly femininity,” Anderson said.

So goes the good life in Santa Fe, and much of it is conducted among the city’s beloved earth-toned adobe and faux-adobe buildings (because the real adobes can melt like mocha ice cream in the rain). At their roof lines, carefully carved wood vigas — the ceiling beams — protrude, and red-pepper ristras dangle. The handsome blue doors and window frames look nice too, but their first purpose (so the folk wisdom goes) is to repel evil spirits.

If only there were a color that tourists could wear to repel high prices. But because there isn’t, be grateful that fall is here and room rates are falling.

If you visit in October — when the aspens and cottonwoods put on golden displays of fall foliage — you’ll probably pay 15% less for your room than the August hordes (who paid $144 nightly on average last year). In November, you might pay 30% less, but you will need a heavier jacket; Santa Fe is about 7,000 feet above sea level, and the average November high/low is 52/26.

No matter when you arrive, you’ll want to check out the dozens of galleries along Canyon Road, where landscapes, portraits, American pottery and Australian aboriginal abstracts abound, at price points of $100 to $10,000. You’ll also want to pay respects at the Palace of the Governors, the long, low structure that faces the plaza, where the Native American merchants lay out their wares along the shaded walkway.

It’s not only the oldest building in town (and a genuine adobe that requires careful maintenance), but it’s also billed as the oldest continuously occupied public building in the United States. Inside, you can browse historical exhibits. Just behind the palace stands the New Mexico History Museum, which opened last year.

The palace has been tweaked and renovated over the years, but this is where the Spanish set up headquarters when they showed up around 1610. When Native Americans rose up and chased the Spanish out of town in 1680, this building was here. When the Spanish retook the town in 1693, it was still here.

And in the late 1870s, when New Mexico territorial governor Lew Wallace turned away from his day job to scribble, of all things, a novel about a chariot-racing Jewish slave/prince named Ben-Hur, this is where he did it. (Long before the Charlton Heston movie, “Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ” was a 19th century bestseller.)

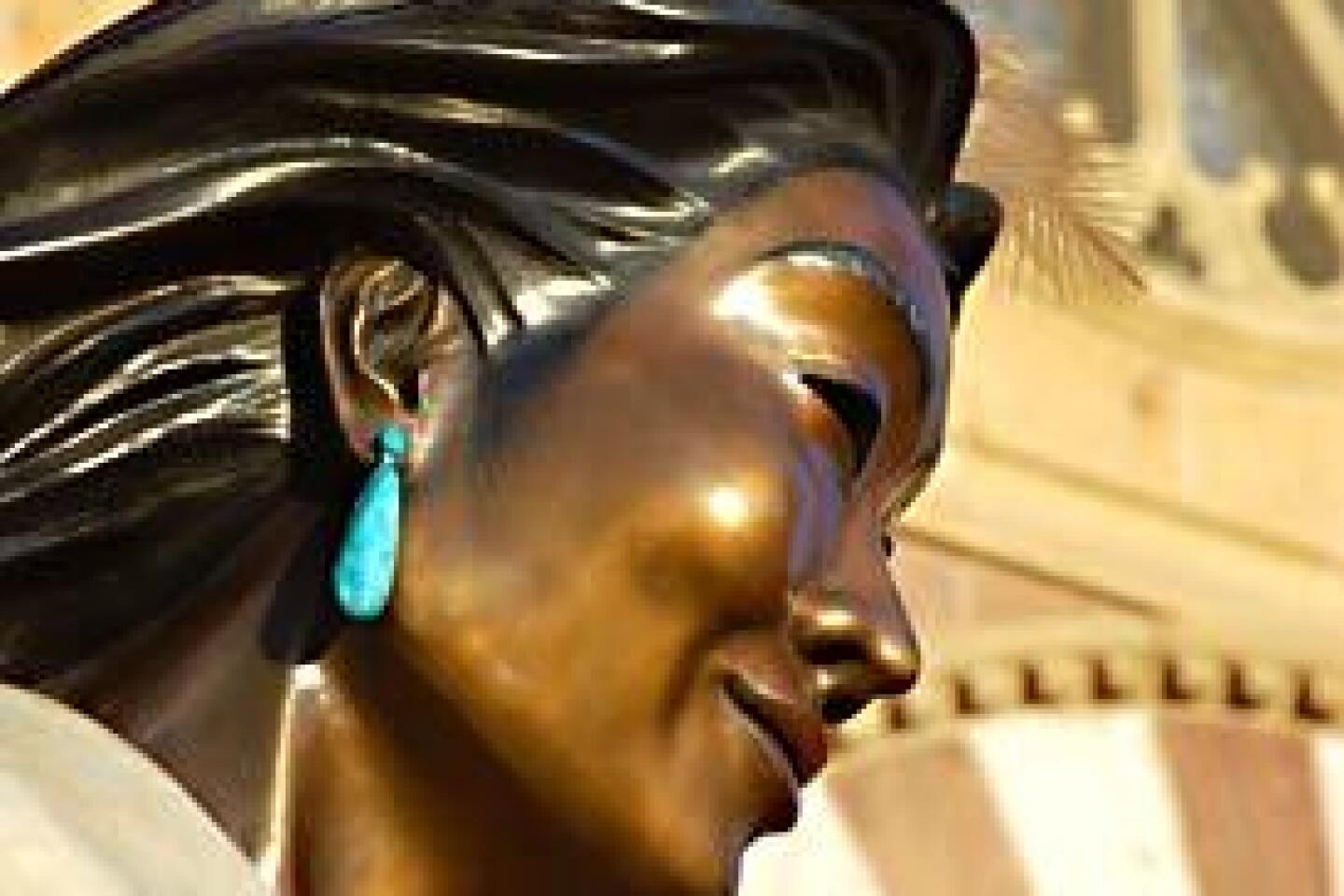

The St. Francis Cathedral Basilica two blocks away will demand your attention as well. It’s a massive stone structure that was put up by 19th century Archbishop Jean-Baptiste Lamy, who came from France and didn’t care much for the adobe look. (Locals persuaded him to leave standing a part of the old adobe church, which is now connected to the cathedral.) In front stands a sleek sculpture of a native maiden, added in 2002, whose beauty might distract you from noticing that the cathedral builders never got around to putting up spires.

Still, of all the handsome old buildings in Santa Fe, the one that stands out for me is the New Mexico Museum of Art, even though, as I’ve just learned from a $1 museum pamphlet, it’s a copy of a knockoff of a facsimile.

It stands just across Lincoln Avenue from the Palace of the Governors, its walls bulging like muscles, vigas jutting smartly, shadows collecting in the courtyard, the works inside telling the story of Santa Fe’s growth as an art colony in the last century or so.

Its inspiration was San Esteban del Rey church at Acoma Pueblo (about 125 miles southwest of Santa Fe), which state historians say was built in the 1630s. But the line that connects them zigs to Colorado, then zags to San Diego.

The zig came in 1908, when Colorado businessman C.M. Schenk hired I.H. and William M. Rapp, a sibling team of architects, to use the Acoma church design as a model for a commercial building in Morley, Colo.

They did it, a group of New Mexico boosters saw the result (which has since been demolished), and soon the brothers were hired to adapt Acoma again, this time as a “cathedral of the desert” to represent New Mexico at the 1915 Panama- California Exposition in San Diego.

Again they did it, to great acclaim. Next came Dr. Edgar L. Hewett, an organizer of the San Diego exposition who was also director of Santa Fe’s fledgling museum. Hewett hired the Rapps to deliver yet another variation on the Acoma theme. So they did in 1917, and that, bolstered with expansions over the years, is the building I’ve been gawking at. (The inside is good too; during my visit, it included a witty exhibit on cowboy boots in popular culture.)

Meanwhile, the original church remains at Acoma, and the San Diego version survives as well (in Balboa Park, though it’s been changed dramatically). But my guess is the Santa Fe art museum building gets the most visitors, inside and out. When I hear somebody say “pueblo revival” or “Santa Fe style,” it’s what I see.

It was tempting to do my eating at the tried-and-true Santa Fe institutions — lunch at the courtyard of the Shed, for instance, or breakfast amid the bustle of Café Pasqual’s. And it would have been another sort of fun to tangle with the fragrance police at Trattoria Nostrani (which has been serving upscale Italian cuisine and banning perfume and cologne for several years). But I was most interested in how Santa Fe renews itself, so I focused instead on new places.

At the Hotel St. Francis, whose small rooms and spacious lobby were renovated in 2009, the new Tabla de Los Santos restaurant served me a spicy Pastel de Los Santos (poached eggs, spinach, corn and chile). At Vinaigrette, a salad-based bistro with a pun-intensive menu and metal chairs of fire-engine red, I had a great lunch salad with pears, pecans, bacon and blue cheese.

I had three excellent dinners. The first was pork striploin at Restaurant Martín, in a low-key bungalow with high-end food, placed just far enough from the plaza to feel more local and less touristy. The second was a farmers market sampler from Max’s, another high-end restaurant with a smaller, and even more casual, dining room. Then there was La Boca (which has been around since 2006), where I sat at the bar in back and tucked into a few tapas and a dessert of fresas de Barcelona (strawberries and liqueur).

Now it was time to see about that neighborhood rebirth along the tracks.

To reach the Railyard District, you head a few blocks west from the plaza on San Francisco, then a few blocks south on Guadalupe, passing such nightlife hot spots as the Cowgirl BBQ and the Corazon nightclub. Then look for the tracks, and the buildings that aren’t adobe.

After decades of civic hand-wringing over the area, the Trust of Public Land stepped up in 1995 to help the city buy the land. Now the nonprofit Santa Fe Railyard Community Corp. manages 50 city-owned acres, having attracted 10 art galleries, four restaurants, one big REI store, several nonprofit arts organizations and the city’s main farmers market. A wood-barrel water tower stands in the middle of it all, a long, shaded walkway slices past, and 13 acres of landscaped open space will eventually connect with a citywide trail network.

Most of those spaces opened in 2008, as did the Railrunner commuter rail service, which connects Santa Fe and Albuquerque, charging just $7 an adult for a 70-mile, 90-minute ride. (If you’re flying into Albuquerque, you can catch a free shuttle from the airport to a rail stop and continue by Railrunner train to Santa Fe.)

The Railyard is also home to the Santa Fe Southern Railway, a tourist train that offers round-trip sightseeing excursions Wednesdays through Sundays on a spur between Santa Fe and Lamy, about 20 miles south.

The idea is to preserve the Railyard’s old grit but also to bring in plenty of free-spending locals and visitors. And clearly the project isn’t done yet: Plans for a Railyard cinema multiplex have stalled for lack of financing, and the tiny old depot building could use some sprucing up.

But on Saturdays, the farmers market draws as many as 7,000 shoppers. And on the last Friday of every month, year-round, the Railyard galleries open for “art walks.”

“This is where contemporary art is really happening in Santa Fe,” said Fiona MacConnell of the Charlotte Jackson Gallery, which recently moved from the plaza area to the Railyard.

With that in mind, I spent a few hours browsing galleries and SITE Santa Fe, a nonprofit exhibition space whose biennial exhibitions since 1995 have won international respect in the art world. The current show, up through Jan. 2, is called “The Dissolve,” and it’s all about the joining of high technology with homespun techniques from the early days of animation. In other words: looking back while looking forward.

Of about 25 mostly video artworks in the show, half a dozen grabbed my attention. That’s a good batting average for me and contemporary art. As I reemerged into the bright light of the afternoon, a few preyed on my mind, especially the miniature drama of Oscar Muñoz’s endless efforts to complete a portrait in water on a fast-drying surface.

While the video camera rolled, the artist would add a new line to the water portrait, but as he did, an old one would evaporate. Then he’d add another new detail, as another evaporated. The watery face was forever evolving, like a slow-motion cartoon, or an old city in subtle but perpetual renewal.

chris.reynolds@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.