New York: In the footsteps of Titanic survivors

Retracing the steps of Titanic survivors a century later gives a sense of old and new Manhattan.

NEW YORK — As you may have heard, the Titanic never reached New York. But about 700 of its passengers and crew did get here on the night of April 18, 1912, three days after the sinking. In fact, their arrival drew a crowd of thousands to the waterfront.

A century later, it’s an instructive adventure to retrace some of their steps and compare Manhattan then and now.

First stop: Pier 54, near 11th Avenue and West 13th Street on Manhattan’s Lower West Side. When the Titanic’s rescue ship, the liner Carpathia, docked at the pier, details of the disaster were still scant on shore. The throngs, gathered to see who had survived, also heard about the 1,500 dead. Local authorities struggled to keep scoop-hungry reporters at bay. Surviving passengers and crew members scattered to local lodgings and hospitals. Just a day later, the U.S. Senate convened a Titanic hearing at the old Waldorf-Astoria at Fifth Avenue and 34th Street, where the Empire State Building now stands.

Much of the waterfront has been transformed too by creation of Hudson River Park and the Chelsea Piers recreation complex. Pier 59, where the Titanic was to have docked, now houses a driving range. But the old metal arch of Pier 54 endures, as does a long platform, sometimes empty, sometimes teeming with revelers. On June 23, the city’s annual Gay Pride celebrations will stage a seven-hour “Rapture on the River” dance there for lesbian, bisexual and transgender women. (Info: https://www.nycpride.org/rapture.php) For a view from above, take a walk on the High Line (a former elevated rail line that’s now a public park) and look west as you cross over West 13th Street.

Second stop, about four blocks south: the quirky old brick building at 113 Jane St. at the western edge of Greenwich Village. In 1912, this was a sailors lodging run by the American Seamen’s Friend Society. It had about 150 cabin-sized rooms (toilets and showers down the hall) where sailors could flop between ship trips. Many Titanic crew members wound up at least briefly in those little rooms, which measured 7 feet by 7 feet.

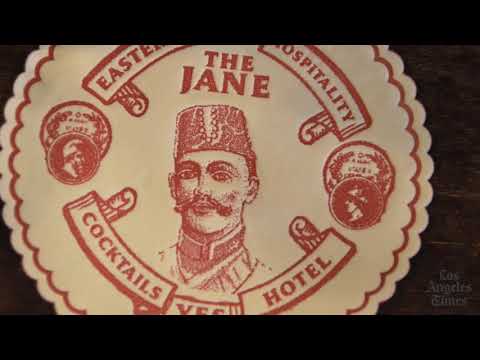

Of course, the building has been revived, renamed and recast since then. It’s now the Jane, a boutique hotel whose bar has been popular enough to generate noise complaints from the neighbors. But here’s the shocker: Those little rooms remain, and you can book a night in one, either solo or in bunk beds. Rates start at $99, and a flat-screen TV has never been more welcome. There are also about 30 larger rooms with larger rates. And the hotel’s restaurant, Café Gitane, features high ceilings, big windows and lots of light.

As long as you’re in Greenwich Village, bow in the direction of St. Vincent’s Hospital at 7th Avenue and West 12th Street, where ailing Titanic survivors were taken. The hospital, founded in 1849, was around to treat9/11victims in 2001, but it closed in 2010. An upscale housing development is planned in its place.

Your third stop, now on the southeastern edge of Lower Manhattan, is a Titanic memorial that was unveiled in April 1913. Back then, it was at the Seamen’s Church Institute at South Street and Coenties Slip. But to find it now, you head for the South Street Seaport at Pearl and Fulton streets, a touristy but mandatory stop for any New York visitor with maritime leanings. The memorial, a 60-foot-high gray lighthouse, was moved here in the 1970s. Let’s just admit it isn’t much to look at. But once you’ve read the plaque, step into the neighboring South Street Seaport Museum (which is full of spiffy new exhibits) and then step outside to gaze at the Brooklyn Bridge (29 years old when the Titanic sank) while munching a $2.50 hot dog from the Nathan’s stand. Then maybe board a New York Water Taxi for a ride past the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island (which both predate 1912).

The fourth stop is Macy’s, on West 34th Street at Herald Square. Isidor Straus, co-owner of the store in the first years of the 20th century, died aboard the Titanic with his wife, Ida. In fact, they’re the couple, in their 60s, who refused to be separated, and they are often mentioned in romanticized renditions of the Titanic story. They are honored more explicitly at the Isidor and Ida Straus Memorial in tiny, triangular Straus Park on the Upper West Side at Broadway and 105th Street, your fifth stop.

While you’re uptown, you can hit the sixth and most far-flung stop on this unscientific, uncomprehensive itinerary: the resting place of John Jacob Astor IV, perhaps the wealthiest of all Titanic victims. He’s buried with several other Astors at Trinity Church Cemetery and Mausoleum, 3720 Broadway, between 153rd and 155th streets in Harlem. He died at age 47, survived by his pregnant 18-year-old bride, Madeleine, who escaped in a lifeboat. Madeleine and their son, also John Jacob, rest near Astor in the same cemetery. For details on Trinity Church Cemetery, go to https://www.trinitywallstreet.org/files/congregation/CemeteryWalkingTour.pdf).

Your seventh stop, below Midtown again, could be just a pause on the sidewalk in front of the Hotel Wolcott on West 31st Street. The Wolcott, just 8 years old in 1912, took in at least three Titanic survivors from San Francisco: Dr. Washington Dodge, his wife and their son. Dodge, a banker who also served as city assessor for San Francisco, was a first-class passenger. He told the San Francisco Bulletin that “some of the passengers fought with such desperation to get into the lifeboats that the officers shot them and their bodies fell into the ocean…. I will never forget the awful scene of the great steamer as we drew away. From the upper rails, heroic husbands and fathers were waving and throwing kisses to their womenfolk in the receding lifeboats.” By the account of Andrew Wilson, author of “Shadow of the Titanic,” Dodge fatally shot himself in 1919.

A first-class passenger wouldn’t settle for the Wolcott today, but I did for two nights. It’s a great find for budget travelers, with presentable rooms for as little as $150 a night.

Your eighth stop, if you can afford it, is the Plaza Hotel, which went up in 1907 at Fifth Avenue and Central Park South. By some accounts, Titanic survivor Lucy Noël Martha, Countess of Rothes, and her traveling party landed here. These days (it’s now under Saudi ownership), much of the building has gone condo, leaving 282 hotel rooms. Employees say the Grand Ballroom, the Terrace Room and the Oak Room have been largely preserved, but they’re open only for special events. The Palm Court looks much as it did in Titanic times, and it’s open for breakfast, lunch and afternoon tea. But a cup of coffee will run you $9.

Stops 9 through 12 are really more about Old New York than the Titanic, but survivors could have dined at the Old Homestead Steakhouse on 9th Avenue near 14th Street (which claims a history back to the 1860s but shows no nostalgia in its sleek dining room) or had a drink at McSorley’s Old Ale House, which opened on East 7th Street in 1854. McSorley’s walls, crowded with memorabilia, include a New York Times “Titanic Sinks” front page. And if the Strauses had survived, I suppose they might have gone (as I did) for a pastrami sandwich at Katz’s Delicatessen. Katz’s, which opened in 1888, may be best known these days as the setting for the “I’ll have what she’s having” scene in the 1989 movie “When Harry Met Sally.”

And for your last stop, how about something that looks beyond the common wealth/glamour/spectacle of Titanic recollections? A short walk from Katz’s, on Orchard Street, you’ll find the Tenement Museum, a 20-year-old restoration and re-creation project that shows the hardscrabble immigrant life that lay ahead for thousands of transatlantic steerage passengers, on the Titanic and other ships. Don’t miss the museum shop, which is full of great books on New York history and architecture.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.