Bali drive leaves them lightheaded

It was late December, and Brian and I were sharing a plate of boiled vegetables in peanut sauce at a cafe in the seaside town of Candidasa on the Indonesian isle of Bali. We were disagreeing about where to go for New Year’s Eve. Both of us thought we should celebrate the holiday somewhere special, but we couldn’t agree on what that meant.

Brian thought we ought to go to a group of three islands in Lombok called the Gilis, small, coral-fringed islands with white sandy beaches, clear water, coral reefs, brilliantly colored fish and superb snorkeling.

“We live on a small, coral-fringed island with white beaches and superb snorkeling,” I said. “We need to come all the way to Bali for that?”

Brian looked hurt. “I like our island,” he said.

We live on Saipan in Micronesia, and I like it too. But I felt strongly that traveling thousands of miles for what we have at home was missing a serious point.

“I want adventure,” I said. “I want to do something that’s going to take me out of my comfort zone.” I was frustrated because we’d already spent a week in Bali doing nothing but pleasant, comfortable things.

The look on Brian’s face said, “Who is this woman?” I relented. We were in Bali for only two weeks, but I hoped to be on the boyfriend’s good side for a lot longer.

“Let’s go for a day trip somewhere today, and then we’ll decide where to go for New Year’s,” I suggested.

Brian agreed, and we set out in our rented car, a cardboard box on wheels.

Twisty road, crazy drivers

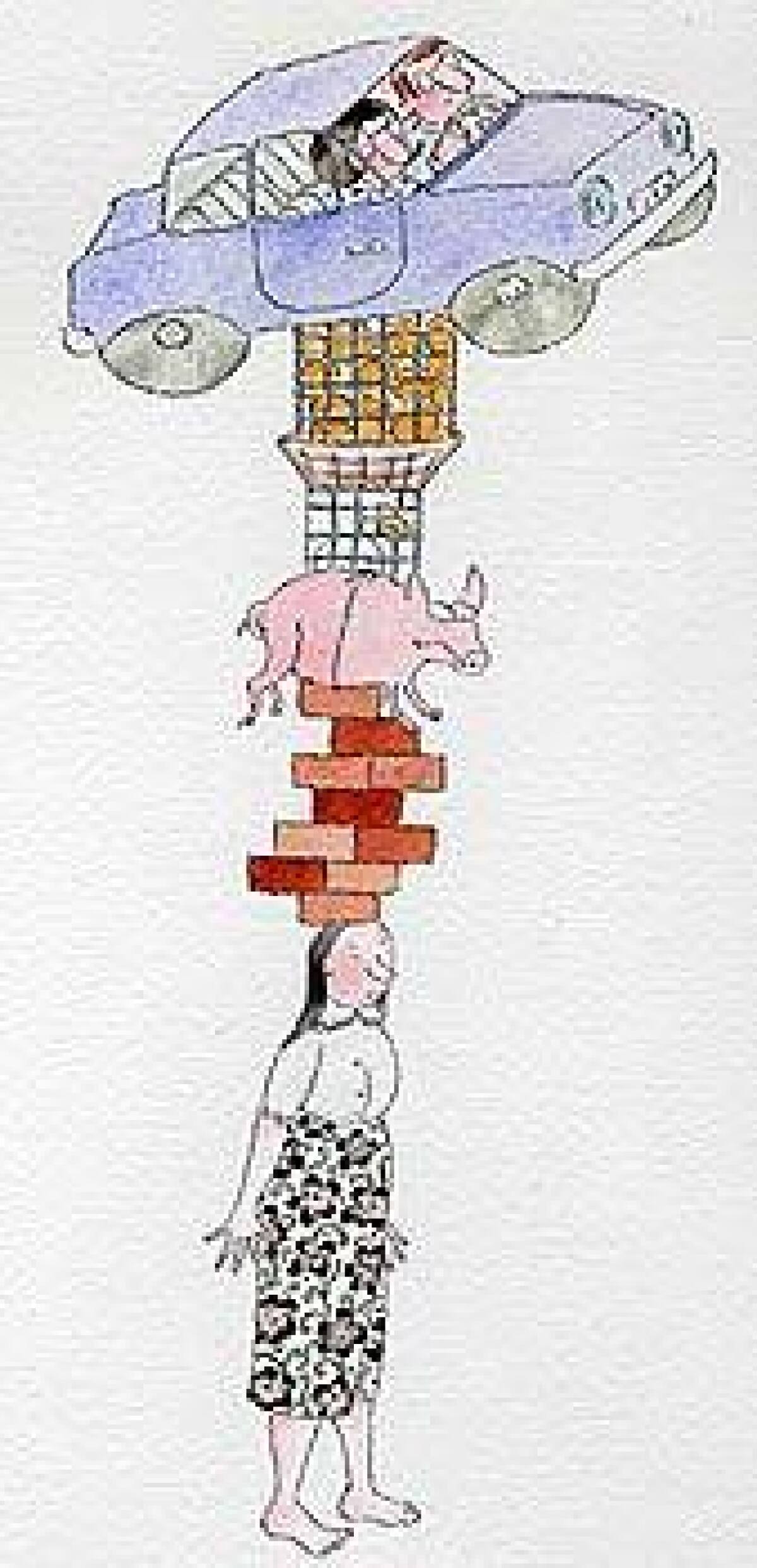

The drive was as frightening and scenic as all of Bali’s drives. The road was narrow and twisty and went by indescribably gorgeous hillside vistas, oceans and temples. We saw a lot of women carrying incredible loads atop their heads: One carried a wheelbarrow, another a pile of bricks. Most loads were simpler: bushels of rice stalks and baskets of fruit.Motorbikes were everywhere, some carrying two, three, four or even five people on a single bike. They thronged the roads, passing one another in the middle of the highway or in the opposite lane, barely avoiding head-on collisions. Cars and trucks did the same.

Brian and I cheered up as we drove: The crazy drivers brought out our appreciation for living. We passed the Bat Cave temple, Pura Goa Lawah, where the day before we had enjoyed looking at thousands of tiny sacred bats hanging in a cave at one of Bali’s most important temples. In front of the temple, a man wearing a sharp tan outfit was standing next to a motorbike. He waved at us. We waved back.

A moment later, the waving man was on his motorbike and was passing the line of traffic behind us. He pulled up by Brian’s open window. “Pull over,” he said. Brian pulled over.

The man stopped his bike behind our car and walked up to the window. He was wearing a fitted khaki button-down shirt with a sewn-on name tag that said “G. Suarta.”

“Why did you not stop?” he asked. “I waved you over and you kept driving.”

Brian looked sad. “I didn’t realize you were pulling me over,” he said. G. Suarta looked unimpressed.

“How fast were you driving?” G. Suarta asked.

“I don’t know,” Brian said.

“Give me your international driver’s license,” G. Suarta ordered.

Indonesian jail time?

Brian pulled out his Saipan driver’s license. Saipan is,technically, part of the United States, but a Saipan driver’s license looks a lot more like a fake ID made by a drunken college student than it looks like a real driver’s license. And anyway, G. Suarta wanted to see an international driver’s license, which Brian didn’t have.

“You need to have an international driver’s license to drive a car in Bali,” said G. Suarta. “Where is yours?” Brian said he didn’t have one. G. Suarta looked angry.

“You will have to come with me to the police station,” he said. “You have done three things wrong: You were speeding; you did not pull over when I waved you down; and you do not have an international driver’s license. Follow me.”

G. Suarta got back on his motorbike, made a quick U-turn and sped into traffic. Brian waited for a hole in the traffic, then turned around into it, but we had lost G. Suarta.

Brian then made another U-turn and started heading back toward the hill carvings. I turned around every few seconds to see if G. Suarta was coming back for us. He was.

He pulled up next to Brian’s window again and said, “Why didn’t you follow me?”

“I tried,” Brian said. G. Suarta told him to try harder, then made another U-turn and sped off again. Brian spun around to follow, but when he was perpendicular to both lanes we heard a loud “smack” in the side of the cardboard car. Brian said some unprintable things as the motorbiker who had hit the side of our car rubbed his head. A crowd immediately congregated.

“Are you OK?” Brian said to the motorbiker, who looked down at his motorbike. Its front was crumpled. Luckily, the motorbiker was not. G. Suarta appeared in the crowd. He directed Brian and the motorbiker to follow him, which we did in a kind of shame parade.

We parked our car, which now had a smashed door. The half-crumpled motorbike was parked next to us. We all followed G. Suarta into the station, where Brian and I were directed into a small room. G. Suarta sat at one side of a table; we sat at the other.

“Where are you from?” he asked. Rather than explaining where the small island we live on is (near Guam), we just said we were from the States.

“I have a cousin who lives in North Carolina,” G. Suarta said.

“Great,” I said, trying to be charming. “Have you been to visit?”

“No.” He turned to Brian. “You shouldn’t have turned there. You were on a curve. It was very dangerous. Obviously.”

Brian looked distressed. “Why didn’t you stop the traffic? Isn’t that your job — to stop traffic?”

G. Suarta was impervious.

“That was a bad place to turn. Now this is No. 4 problem.” He asked for Brian’s driver’s license again and started writing down the information on it. I kept wondering what Indonesian jail would be like and how long it would take to learn Indonesian sufficiently to talk with my fellow inmates.

“You damaged the motorbike. You should pay to have it repaired.”

Was he asking us to bribe him?

“How much will that cost?” Brian asked.

“Maybe 150,000 rupiah,” G. Suarta said. It was less than $20. I stopped worrying about jail and started feeling grateful for cops who could be bought off for very little money.

Brian and I came up with the money. G. Suarta called the motorbiker into the room.

G. Suarta handed him the money. “I want you to take note that I am giving this man all the money. I am not taking a bribe. The Indonesian police do not take bribes.”

The motorbiker took the money and left. G. Suarta asked Brian to sign a scrap of paper with nothing on it except the information from his driver’s license. Then we got out of there and resumed our drive south.

We were both quiet for a while.

“I think the beach sounds quite nice after all,” I finally said.

“Doesn’t it?” Brian answered.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.