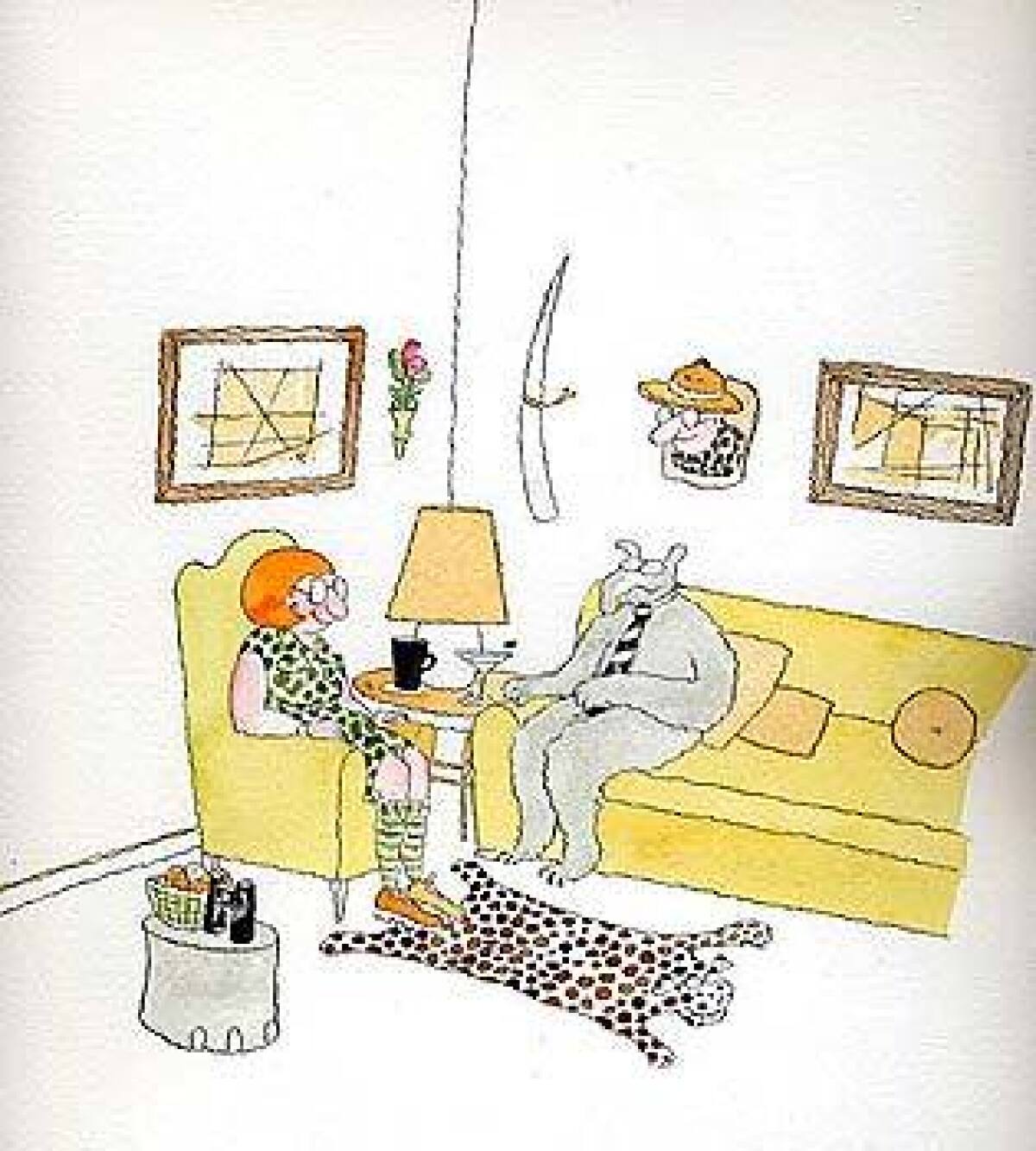

Look who came to dinner: Hairy

Three hobbled horses tore up the embankment like wildly rearing rocking horses, then stood stock still, ears pricked and rigid. My family and our two guides were eating chicken legs by campfire. Having gone to fetch a sweater from the tent, I paused to wonder at the horses’ sudden fright. I approached the big brown Morgan and stroked its neck. It remained taut, alert.

Jake, our 12-year-old son, called to me. “Hey, Mom. Bear.”

The giant head of a grizzly bear loomed just beyond the campfire. It sniffed the air and peered at us, as if it couldn’t quite believe its eyes either. I had never seen a bear in the wild. Now its visit seemed preordained.

When my husband, Michael, our sons Jake and Will, our guides, siblings Russ and Jamie, and I had returned from a day’s ride in Wyoming’s Teton wilderness, we discovered that our campsite had been wrecked and looted. Locked bear-proof boxes were tipped over, latched coolers were riddled with teeth marks. A can of condensed milk had been squeezed empty like a juice box. Having pried open a cooler, the bear had polished off everything but the wine.

“It doesn’t look like organized crime,” said Russ.

So the stories about prowling ursine vandals weren’t exaggerations. And neither was the precaution of keeping a canister of bear pepper spray in each tent. Aim for the eyes, Russ and Jamie had told us. Neither they nor their dad, who had been leading wilderness pack trips for nearly 20 years, had ever spotted a bear near camp.

I know from experience, as a journalist who once lived in Africa, that chancing on animals in the wild is a privilege and a piece of luck. At the first whiff or sound of a human, they usually flee.

But sometimes wild animals don’t follow that safety drill. When people get into trouble with animals, it’s usually not because of beastly malevolence but because of over-civilized stupidity and because people forget that a wild animal is just that; it won’t tolerate taunting or having its young stalked with a camera.

Once we had cleaned up the mess, we thought no more about the raid. While Jamie cooked dinner, we took turns reading cowboy doggerel around the campfire. The roasting chicken and potatoes smelled awfully good.

On that point, we and the bear agreed.

Consider it from the bear’s point of view: Lunch had been delicious, and from the scent wafting in the night air, dinner promised to be spectacular. But something was wrong. At lunchtime, the grizzly had had the restaurant to itself. Now, other guests had claimed its reserved table.

The grizzly saw us, but it didn’t take off. But neither was it particularly menacing. The humpbacked creature, with a heavy head and a slow gait that revealed raw power, hovered, lumbered closer, squinting and sniffing, unsure what to do next. If it had really wanted to attack us, we were easy pickings. We couldn’t have outrun the creature. Grizzlies can run 35 mph.

And I can’t.

Jamie and Russ kept their little cans of pepper spay poised.

Michael picked up his video camera. I retrieved my binoculars from the tent and urged them on our boys.

“Look at this. Look!” I said, dumb awe having reduced my speech to Dick and Jane. “You’ll never in your life get an opportunity like this. Look!”

Will, who’s 11, is not keen on those once-in-a-lifetime experiences that also risk being end-of-a-lifetime experiences. He was plainly terrified. He didn’t want to look and tugged at the binoculars so I wouldn’t look either, as if my curiosity might offend its subject.

The bear moved closer to the campfire, and we backed off slowly, staying a good 30 feet behind Jamie and Russ. We were all torn between fear and fascination, but my scale tipped more toward the latter.

Russ hurled a piece of firewood — not a great move in my opinion. Clap your hands. Bang pots and pans. But don’t taunt. The firewood sailed past the bear. It didn’t seem to notice.

We were locked in a very slow cha-cha, with the grizzly leading. As it moved two steps forward and rocked one step back, we edged away facing it. But then Russ, who had watched one too many westerns, decided on a sneak attack. He circled behind the bear and shinnied up a tree, leaving his sister Jamie, with her can of pepper spray, to hold the front lines alone.

Russ hurled another branch and missed again. Just as well, I thought. The grizzly wasn’t going to ruminate on who the real pitcher was. To its myopic eyes, Jamie was now Target No. 1.

“Go climb trees,” she whispered to us urgently. “And don’t come down till we tell you it’s safe.”

Euphoria seized me. I wanted to watch. I had to watch. This spectacle was more thrilling than the night I saw Barry Bonds reach Mickey Mantle’s home-run mark. I could not believe, I refused to believe, we were in danger.

To me, the invisible shield that had always protected me in my solo travels in the wild extended to my family. I wanted them to see this rough beast slouching toward our leftovers. And now our young guides were telling us to take a hike, climb a tree.

“Put the binocs down!” Jake said.

“Why? You think I’m making the bear self-conscious?”

Will tugged at my arm. “Come on, Mom. You’re acting weird.”

“The grizzly doesn’t want us, Will.” This was Mom speaking, the voice of calm and reason masking the adrenaline surge. “All he wants is our dinner.” I squeezed Will’s hand.

“We’re going to climb a tree,” my husband said, sotto voce. “Right now.”

Naturally I objected. But not all that strenuously. Grizzlies, after all, eat meat. And in these particular circumstances, our status in the food chain had slipped precipitously. Our little troupe of four trudged back to the darkening woods.

Real tree huggers

Finding a tree with sturdy, climbable limbs in a forest of spindly lodgepole pines was not easy. The live pine branches were too springy. The foot slips, you slide and end up on the ground with a backside full of needles. The dead trees were so brittle the branches snapped. Jake found a pine with a split trunk. He shimmied up maybe 15 feet, just out of claw’s reach. My husband boosted Will below Jake, maybe 10 feet up. Michael was bottom man, an easy grab if the bear felt like having an hors d’oeuvre.From his high perch, Jake peered down at his clinging brother and his father and his weird mother below on the forest floor.

“Thanks for the trip, guys, but this is one time I wish I were having a deprived childhood,” Jake said.

I left them to find my own tree, but my heart wasn’t in it. I felt ridiculous. For starters, I hadn’t thought of packing telephone lineman’s cleats for a wilderness camping trip. Moreover, I didn’t want to confuse the grizzly. On the ground, standing up and facing it, I looked like a person. If I bloodied myself in a clumsy attempt to clamber up a tree, the bear might mistake me for a blond raccoon. More to the point, I knew, deep in my thudding heart,this grizzly had better things to do than shake tourists out of trees like coconuts.

Back at the campfire, the bear had crossed the goal line. It had eaten the last piece of chicken, the potatoes, the very tasty three-bean salad and was contemplating dessert when one of Russ’ wood missiles glanced off its head. Now it was clearly miffed.

Like a circus bear, it gingerly mounted a tree stump we’d been using as a stool, then rose up on its hind legs. For grace, athleticism, presence and dramatic presentation, I would have given it a 9.6. Counting the tree stump, the undisputed king of the mountain was about 11 feet tall and had a good view of the puny enemy who was interrupting its supper. It leapt from the stool and charged but stopped abruptly. It was only a display charge. The grizzly ambled back to the camp table, sat down on its haunches and devoured our brownies. Then it sauntered off to digest.

It was not far off, though. The horses snorted and stomped. They smelled the bear.

Time to figure out a new tactic. Russ and Jamie suggested we set up a tent in the forest near the horses. They radioed their dad in Driggs, Idaho, about five hours away by horseback.

“Dad’s saddling up,” Jamie said.

“He’s got a sawed-off shotgun,” Russ said. They would stay up by the campfire until their father arrived.

Michael, the boys and I set about pitching an unfamiliar tent in twilight. Picture a confrontation from “Survivor” crossed with a fiasco from “Fawlty Towers.” We could find only three tent stakes out of six, and nobody volunteered to search the dark woods for the others.

Michael muttered, pounding sticks with rocks into hard earth. The tent listed one way, then another, before collapsing. Finally we managed to erect our fragile fortress and zipped ourselves inside. All four of us lay sandwiched side by side, mama and papa bears in the center, our boys bracketing us. The can of pepper spray glowed comfortingly in the dark. A horse snorted. Or was it the grizzly? Jamie and Russ waited. Now and then their flashlights, aimed into the brush, fixed on a pair of eyes shining back. The bear was waiting too. I heard Jamie’s nervous laughter.

I didn’t deeply fear for our safety. Why not? Fear was reasonable under the circumstances. It simply hadn’t hit me. Maybe it had been transmuted into elation, then numbing fatigue. The horses grew quiet. The boys’ even breathing lulled me. The tent felt warm and secure, and all that had gone before dissolved into the closeness of the present — mother, father and two sons packed together like shrink-wrapped sausages.

Three gunshots jolted me from my half-sleep. I sat bolt upright. Oh, good. Dad’s here. But please don’t kill the bear. Why? Because it’s the grizzly’s territory, and we are interlopers. Because drought has made the bear desperate for food. Because it hasn’t threatened us; it is out for brownies, not blood. Because, Ladies and Gentlemen of the Jury, the grizzly bear is an imperiled species. The defense was still summing up when four more shots shattered the darkness.

Asleep in their pods, our two boys didn’t stir. Nothing more rocked their sleep, nor mine nor Michael’s, until dawn.

The next morning

Jamie and Russ’ dad, Kevin, were brewing coffee in a blackened pot. The campsite was strewn with .30-06 shotgun shells. Michael was the last to rise. He was smiling and chipper, though a little disappointed, he said, that there wasn’t a new bearskin rug at the campsite.“Are you a better shot in the day than you are at night?” Michael asked Kevin.

“I shot over his head,” said Kevin. “If I had killed him, I probably would have lost my guiding license. I did just enough to discourage him. I suspect he’s picking buckshot out of his backside now.”

We saddled up, rode out of the wilderness at a good clip and boarded a jet. Will couldn’t wait to tell his friends at school. Michael took his digital grizzly footage to the office to show the gang. Jake collected the empty shotgun shells as trophies for his bookshelf.

As for me, I’m still poring over — no, being pawed by — strange emotions. What sort of misanthrope sides with the grizzly? In my revisionist version of Ernest Hemingway’s famous safari tale, “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber,” Mrs. Macomber shoots her cowardly husband not because she fancies Wilson, the White Hunter. No, by this time she has had it with both the macho man and the wimp. She bags them both and elopes with the bear.

Harriet Heyman writes, bear free, from San Francisco.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.