An illuminating deep water dive off Hawaii’s Big Island

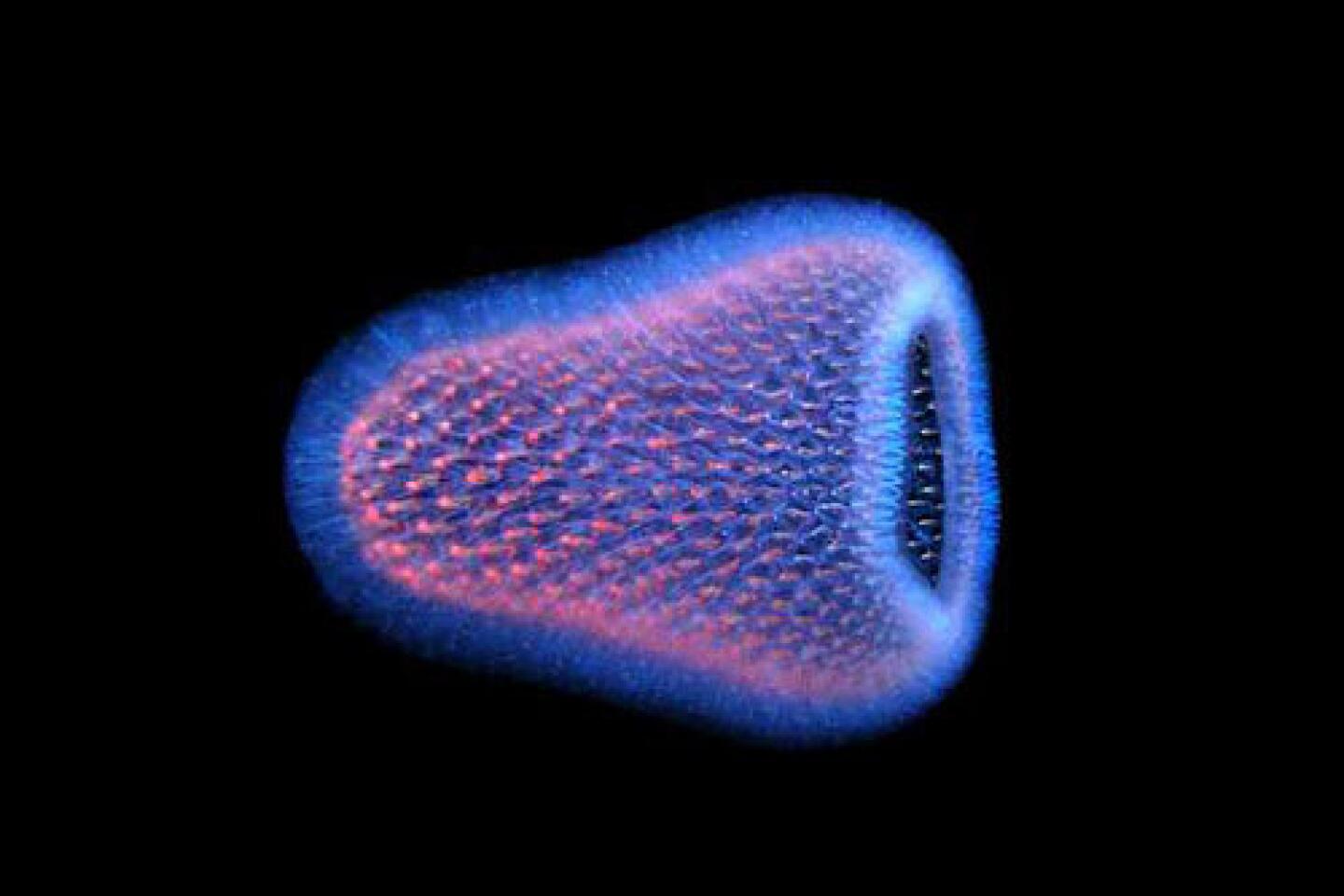

There’s dark, really dark, and then there’s Matthew D’Avella’s spine-tingling black-water dive, a deep-ocean adventure on which divers, hanging like marionettes from weighted lines under the boat, seek close encounters with astonishing gelatinous creatures rising from the abyss at night to feed. These small and profoundly strange animals, some twinkling with iridescent cilia, others burning with an inner fire of bioluminescence, have drifted through the night seas for billions of years.

“The youngest animals, evolutionarily speaking, you’ll see are among the oldest on Earth,” says D’Avella, who has been running these excursions out of the Big Island Divers shop in Kailua since 2006. D’Avella, 39, is a woodworker by trade, but he’s more a throwback to an era of self-taught gentleman naturalists. The big, broad-shouldered native Philadelphian, who first took the black-water dives in 2000, has developed a passion for some of the ocean’s smallest and least understood creatures.

“It just became an addiction,” he says. “It’s amazing. You are surrounded by animals you thought only existed in Hollywood.”

The Big Island is an excellent venue for the dive, because of the steepness of its seamount. Just two miles offshore, the water is thousands of feet deep. “We used to do the dive 10 and 20 miles out,” he says. “Then we realized there was more to see closer in.”

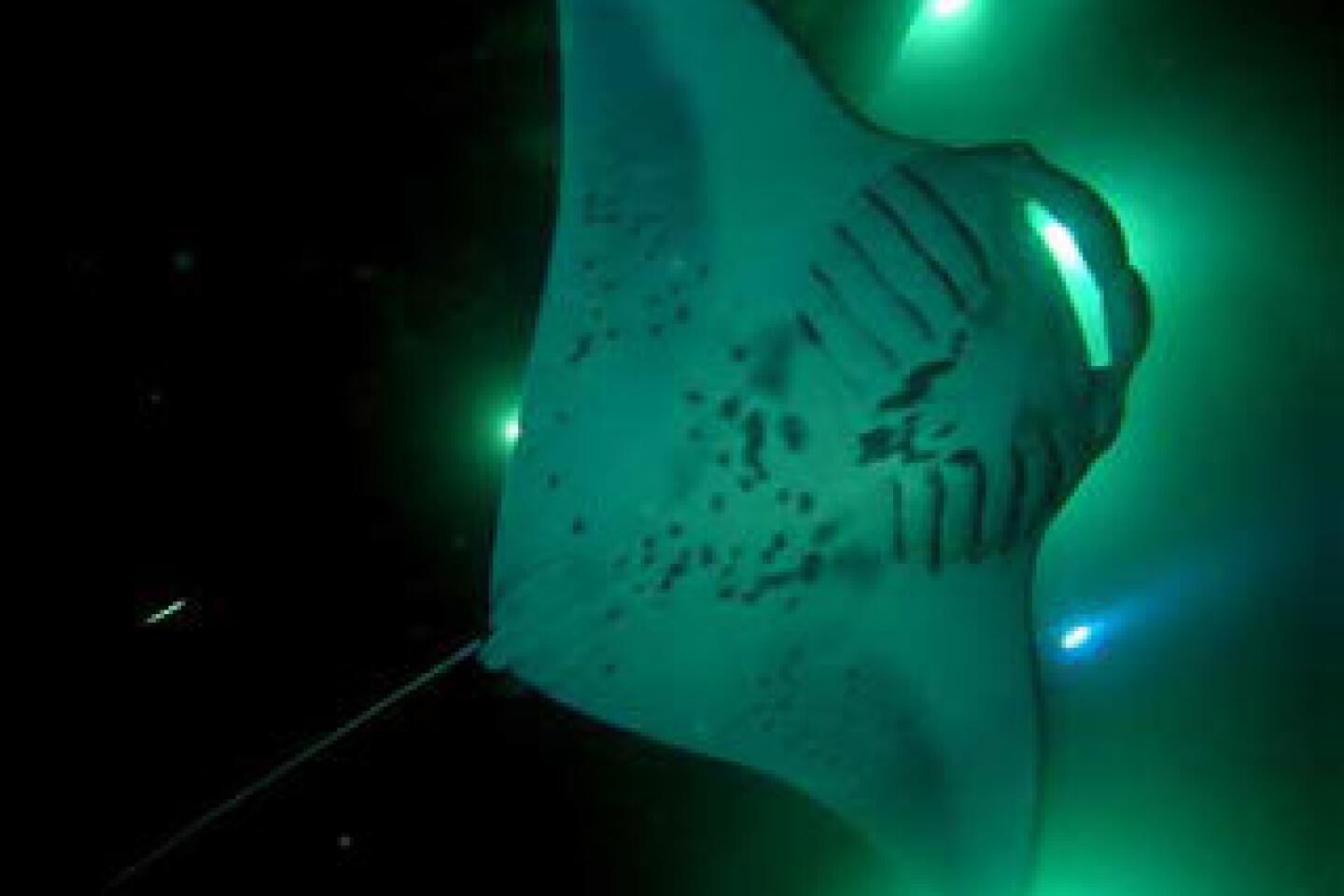

D’Avella’s black-water dive, a night trip he conducts on Mondays, is the only regularly scheduled dive of its kind on the Big Island. For safety reasons, he requires divers first to go on a manta-ray night dive to evaluate their comfort in the water.

The dive, D’Avella stresses, is not for everybody. He takes only accomplished divers, and even for some of them, the experience of stepping off into 7,000 feet of water can be unnerving. “I’ve had serious open-water divers walk on water to get back on the boat,” says Trish Morris-Plise, who mans the boat while D’Avella is in the water.

Even though the dive, with a maximum depth of about 45 feet, is not technically demanding, “it’s a sensory overload thing,” D’Avella says. It is, after all, a very big ocean. Divers can have an alarming moment of clarity in open water. “You realize that you’re now part of the food chain, and you’re not at the top ... nowhere near the top, really,” he says.

The biggest concern is large ocean predators that can suddenly appear out of the dark. D’Avella has seen blue sharks, an oceanic whitetip shark and a broadbill swordfish that swam toward him slashing his bill. “My first thought was all the marlins I ever killed,” says D’Avella, who has sworn off fishing.

He means for the dive to be an intimate encounter with deep-water zoology, a learning experience, not a blood-and-guts adventure. And yet, he says, “I’m scared every time I go out.”

D’Avella takes a maximum of five divers, and on a recent night, I suit up with four other adventurers and head out into the moonlit ocean on Big Island Divers’ 35-foot dive boat. After a few minutes, Morris-Plise cuts the engines. The lights on the Big Island glow in the distance while we wrestle into our gear. Each diver is tethered to a weighted 40-foot drop line by a 10-foot johnny line. “You want to be scared?” he says to his party. “Then go first.”

A breathless step into the cold, solemn darkness. I switch on my diving light and sink to the end of the line, tasting the wintry air in my regulator, listening to its regular rasp.

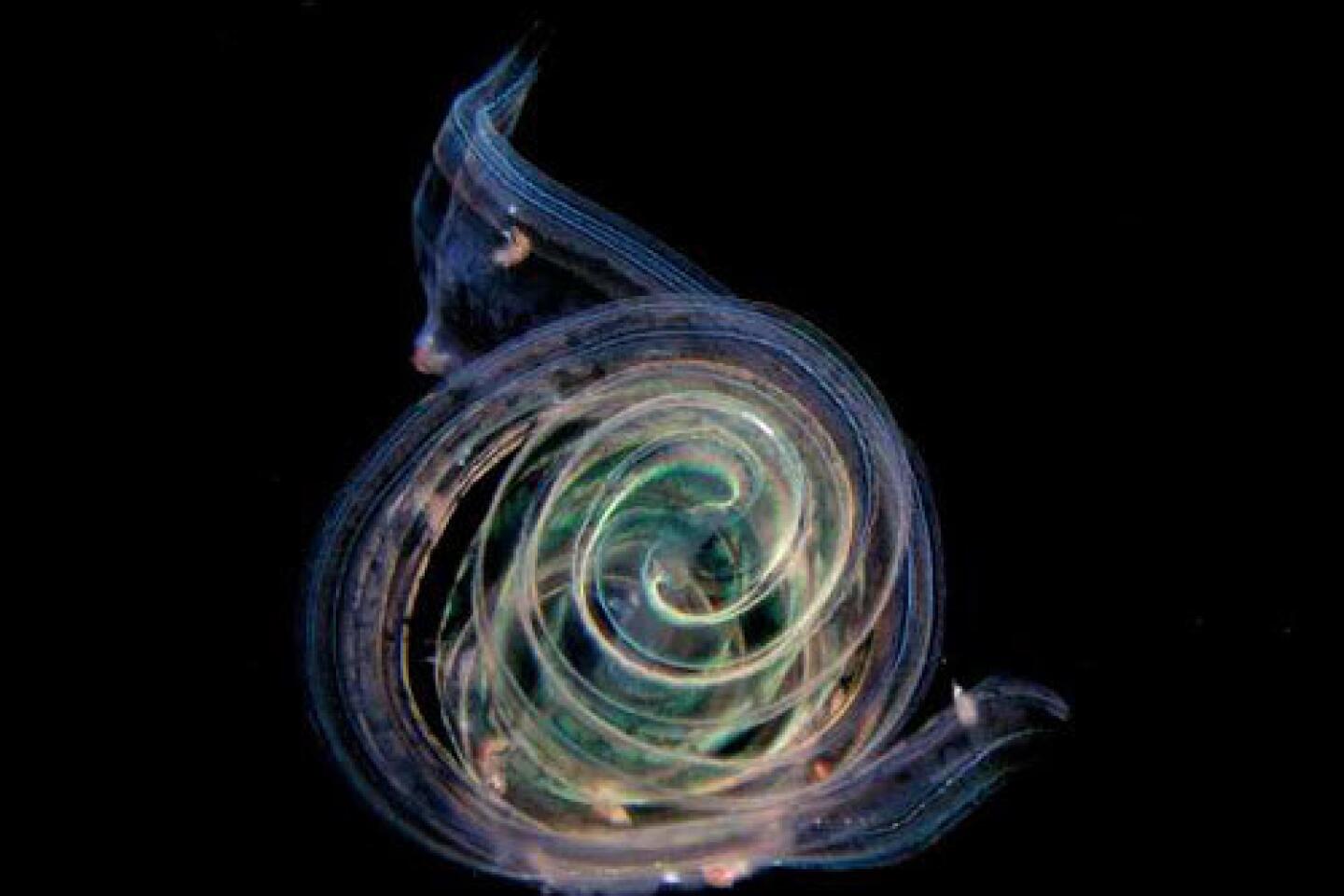

Almost immediately, in the light’s pale beam, a Venus girdle floats by, a translucent ribbon about 2 feet long that moves in the water like a woman’s windblown silk scarf. The creature’s edges are outlined in kinetic rainbows — the iridescent cilia. Then a pelagic shrimp swims by. And then half a dozen other creatures, some so insubstantial and diaphanous they seem to be drawn in negative space. Most of the deep-water invertebrates, D’Avella tells me, are 90% seawater.

One tiny, jelly-like creature casts out a skein of thread-line tentacles and, when it catches a bit of zooplankton, suddenly reels its tentacles in. Another Venus girdle wraps itself around my drop line, and I gently loosen it from the tangle. Other delicate scraps of life swim past. At one point, I look around to check on my fellow divers, all suspended in the blue-black void. Each is intently focused on some creature or another, so small I can’t even see them. It’s no wonder big predators can catch them off guard.

Though I’m not aware of my breathing, I use up my air twice as fast as I usually do. Before my air runs out, I sweep my light out into the pitch-black ocean for one last look at the night sea that once might have seemed so empty but now seems so full.

dan.neil@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.