Night diving among the manta rays on the Big Island of Hawaii

One big step off the boat and into the dark. When I hit the water, I feel all the familiar feelings, the ocean seeping into my wetsuit, the frantic bubbles on my face, the ineffable moment when the body’s gyroscope switches over from gravity to buoyancy. But nothing else is familiar. I’m floating free in the blue-black ocean, a few hundred yards from Kona’s volcanic bluffs. The water is about 40 feet deep here, but just a few hundred yards to the west the Big Island’s seamount plunges into the miles-deep oceanic abyss.

A quarter moon silhouettes the dive boat Honu 1, where the dive masters are tossing out flashlights to their clients bobbing in the dark. Each diver has a couple of illuminated chem-sticks attached to his or her tank. Tonight the Honu 1’s divers are wearing green chem-sticks — the green team — to distinguish them from the three dozen or so divers from other boats that are moored around us.

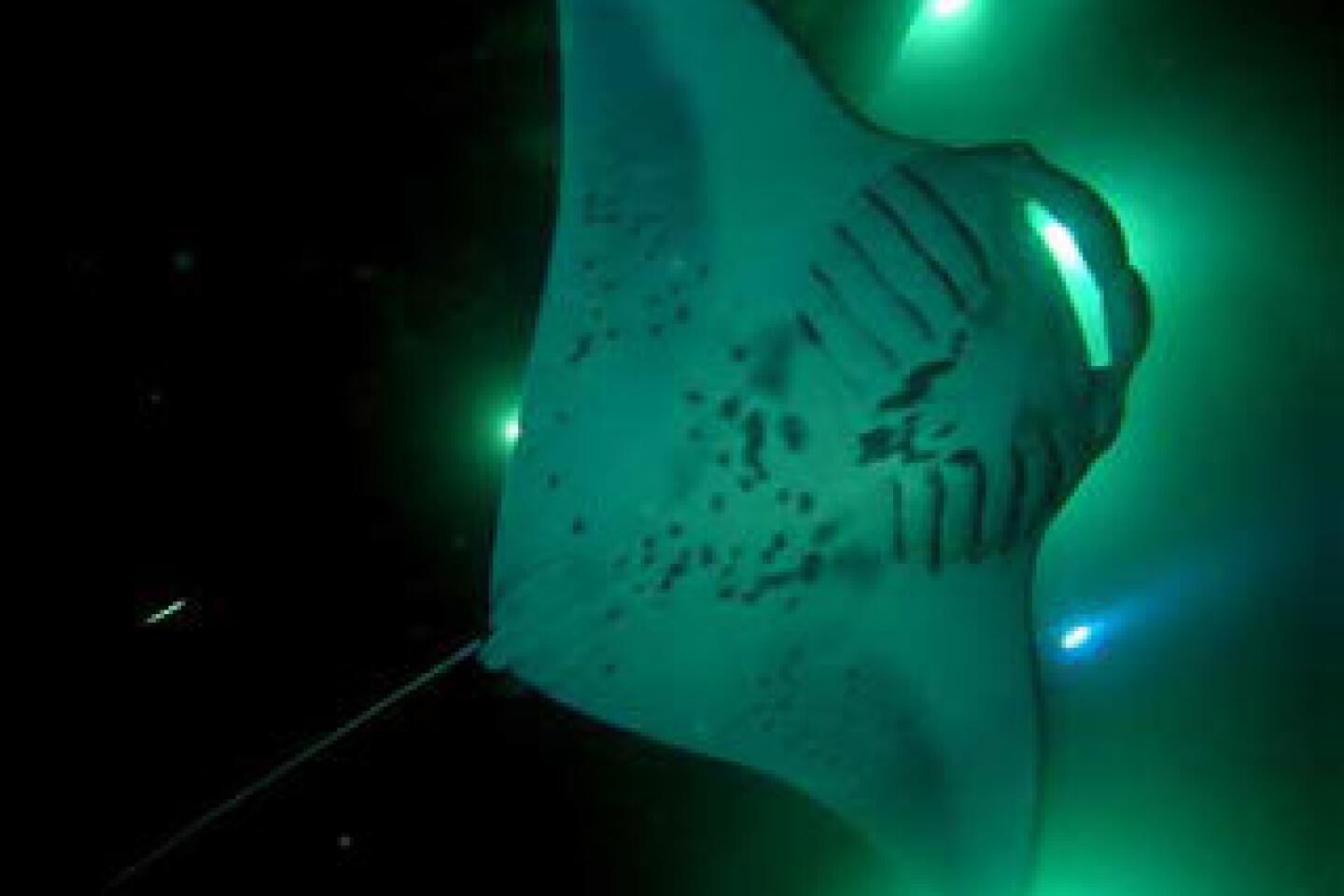

During the day, this area is known as Garden Eel Cove — a more-or-less routine Hawaiian coral dive — but at night the locals call it Manta Heaven. Here, attracted by the abundance of light-seeking phytoplankton, the Big Island’s resident manta rays (Manta birostris) come to feed. It’s a classic symbiosis: The divers bring the lights, the lights bring the plankton, the plankton bring the mantas, and the mantas — huge but harmless creatures that swim in exquisitely slow arabesques in the spotlights, like dancers through an opium dream — bring the divers from around the world, by the thousands.

This is the Big Island’s famous Manta Ray Night Dive, frequently rated one of the top 10 dives in the world and pound for pound the most surreal encounter you are ever likely to have with a big marine animal.

“When people come back to the boat, they don’t know what to say,” Konahonu Dive Shop’s Rich Sanchez told me earlier that afternoon. “One lady came up crying, saying she’d had a spiritual happening.”

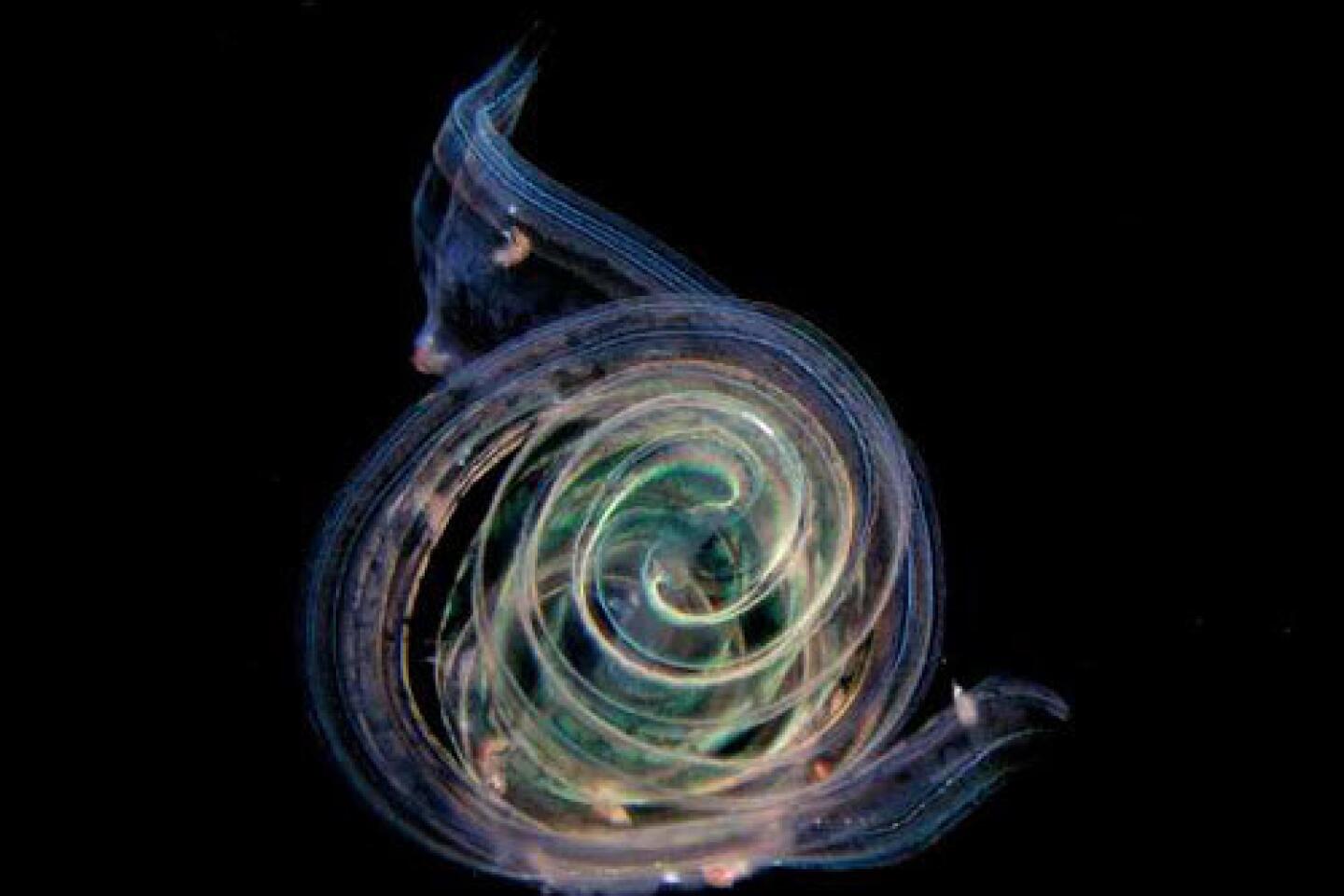

At about 8 p.m., my group’s dive master, Tim Lenarsky, signals for us to descend. I bite into my regulator and squeeze the air-release button on my buoyancy compensator vest. Slowing sinking into the dark, with the faint, netted light rippling across the coral below, I can see in the distance the area they call the Campfire — a rough circle of lava rock on the bottom where the divers place upturned underwater torches. A column of blue-green light glows from the bottom, and swirling above is a funnel of silver Hawaiian flagtails, like a small glittering tornado.

The divers are instructed to sit or kneel on the bottom and hold their lights over their heads, and as I level off and begin kicking toward the area, the scene reminds me of a movie premiere when searchlights sweep the skies above Hollywood. But then a manta flies through the beams and I think instead of London during the Blitz.

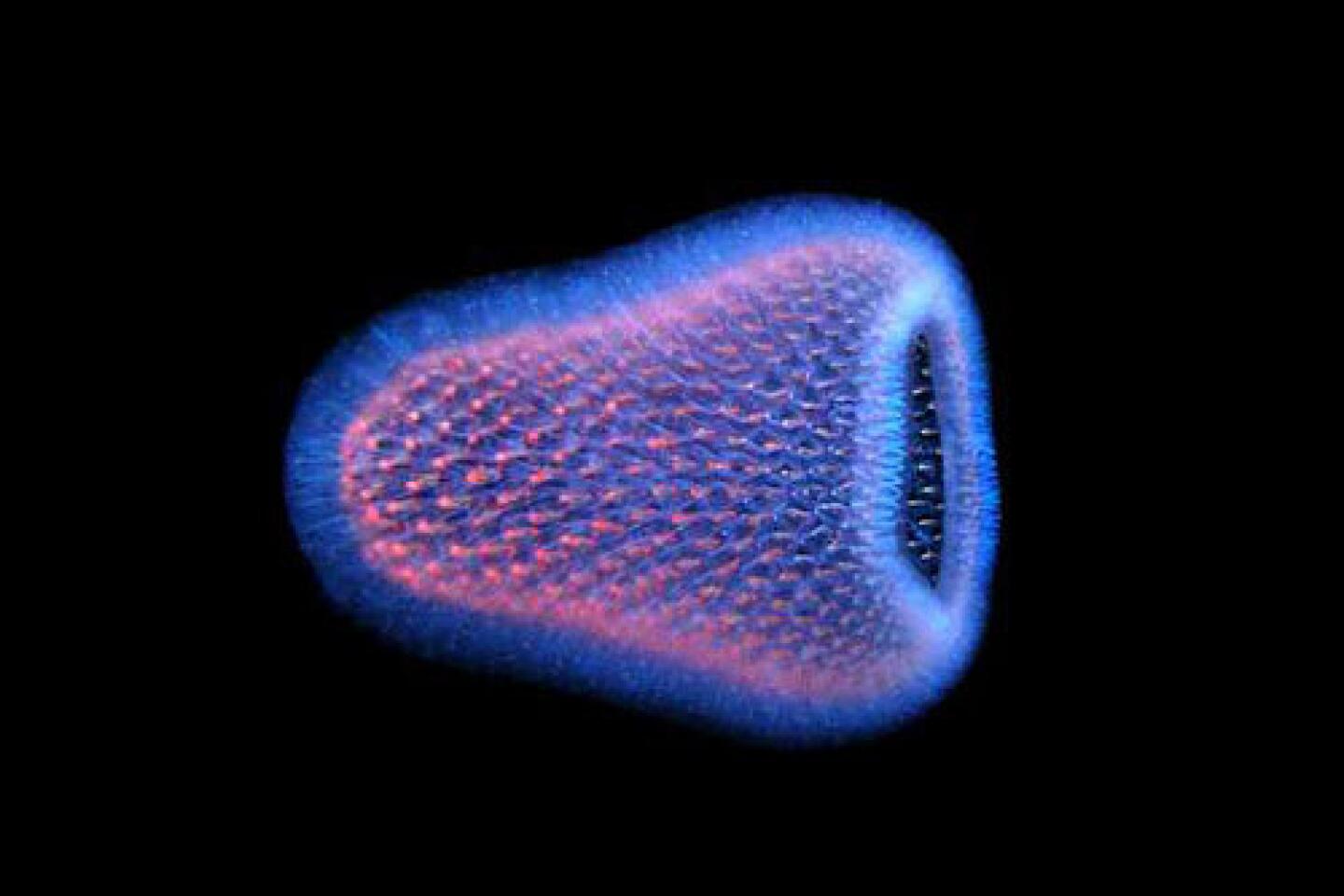

Manta rays are essentially winged gullets, and to see one swimming at you is to stare down the mouth of Creation. Mantas, which can grow to have a wingspan of 20 or more feet and weigh up to 3,000 pounds, are the largest rays in the ocean. Millions of years ago, these animals evolved away from their smaller bottom-feeding cousins, stingrays (which got a bad rap with the death of naturalist Steve Irwin), to become great oceangoing vacuum cleaners. The series of gill plates inside their maws incorporates mesh-like structures that collect whatever the animals scoop up — plankton, fish larvae, copepods — and moves it toward the esophagus.

Mantas (the name comes from the Spanish word for “cloak”) were known to early mariners as devilfish because of the horned projections from their heads. These are, in fact, cephalic fins that help direct food to their mouths. There is nothing remotely threatening about mantas except their appearance.

I know all this before I settle myself on the sandy bottom (picking up a lava rock for added ballast) and yet the first time one of these animals sweeps out of the dark to buzz me, I get a lump in my throat. Because mantas are covered with a thin layer of protective slime, divers are not allowed to touch them (and doing so will get you kicked off the dive). Divers also remove their snorkels so that the mantas don’t scrape their bellies on them. That allows the mantas to come within an inch or two of the divers. I feel water turbulence from the mantas’ powerful wing strokes on my face.

Soon, drawn to the lights and the promise of thick zooplankton, four mantas come to the spot and begin wheeling and banking through the lights. The streams of divers’ bubbles rise like fronds of sea kelp. Curious squirrelfish, brownish silver in daylight but red at night, swim up to my faceplate.

People don’t need to be scuba-certified to go on the dive. Three of our party — a family from Canada — are snorkeling on the surface, their flashlights following the mantas like balcony spotlights. Indeed, there’s something strangely theatrical about the manta dive, as the animals swim through a proscenium of luminous bubbles. Because you can’t see the microscopic prey they feed on, the mantas’ circling and back somersaults appear random and unmotivated, as if they were just showing off. This is the Las Vegas of marine biology or, maybe, the Cirque du Soleil.

“It’s dinner theater,” Matthew D’Avella, a veteran Big Island dive master, told me. “They’re here for the dinner and you’re here for the theater.”

The mantas’ movements have a melancholy elegance about them, like the flare of a matador’s cape in slow motion.

Sleek and soign, with a velvety black on their dorsal side and creamy white on their bellies, the mantas must feed endlessly. The animals consume about 10% of their body weight per day, according to Tim Clark, a manta biologist. That means a 2,000-pound fish must consume 200 pounds per day. Mantas are distantly related to sharks, but the ocean-grazers’ eyes look more bovine than predatory.

As I watch the gyrating animals, I feel a tickle across my legs. A very large undulated moray eel is swimming across me. This is Frank, who, I am assured, is curious and amiable, by moray eel standards. According to dive master Jason Radwick, Frank will only bite defensively, and Radwick has the bite mark to prove it.

There are 107 identified mantas that are residents of the Kona Coast, according to MantaPacific.org, a manta ray advocacy group based on the Big Island. The dive masters know them by name. Tonight, “Lefty” — a large female with a broken left cephalic fin — makes an appearance. Lefty was the first Kona manta to be identified back in 1979, and she was a regular visitor at the Kona Surf Hotel (now the Sheraton Keauhou). The hotel’s floodlights attracted mantas as far back as 1971 and was the previous site of the manta night dive. When the hotel closed for remodeling in 1999 and turned the lights off, the mantas migrated 16 miles north to this spot just west of the Kona airport. The Sheraton turned the floodlights back on when it reopened in 2005. The mantas have returned to the spot, and hotel guests can take a convenient night-dive trip just offshore to see the animals.

Like virtually everything else in the ocean, the mantas are under pressure from man. They are being aggressively fished in Asian waters, but the Kona mantas live in protected waters and, judging by the number of young, the population appears to be healthy. Tonight, Koie Ray (whose left cephalic fin has been amputated by tangled fishing line), Timbuktu and Knight Ray make an appearance. The biggest Kona ray is Big Bertha, who is 16 feet across.

D’Avella and others in the tightknit dive master community are devoted to these animals.

“We’re pretty crazy about them,” he says. D’Avella recalls how he managed to cut 600 feet of fishing line off Knight Ray. The animal returned the next two nights and, D’Avella says, sought him out so he could cut off the remaining line.

“The first 100 times you do this dive, it’s fantastic,” D’Avella says. “The next hundred dives, it gets incredibly boring. And then something clicks; a connection is made.”

After 45 minutes or so, the divers’ air begins to run out, and they start rising to the surface — all tanks and fins and hoses, comically awkward visitors in the realm of the hydrodynamically perfect manta. It’s been spectacular.

One by one the lights go out, and the manta rays slowly disperse, disappearing into the moonlit sea on lazy strokes of their enormous wings, not even bothering for a curtain call.

dan.neil@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.