Tour of Japanese cuisine with Spago Beverly Hills chef Lee Hefter

Tokyo

Big, burly Lee Hefter barrels through the streets of the Ginza district on a cool spring night in hot pursuit of a pastry cook. With very few words of Japanese, Hefter has persuaded the man to dash out of his shop and lead the way to Shotai-en, an obscure restaurant specializing in Japanese beef.

Here it is, motions the cook, indicating the doorway of an office building. This is the place.

Arigato gozaimasu, thank you very much. And the cook runs off again.

An elevator up to the ninth floor, a quick exchange with the host, and before we know it, Hefter, the executive chef at Spago Beverly Hills, is ordering beef sashimi, beef tartare, two kinds of salad, vegetables for grilling, shrimp on skewers, three kinds of Wagyu beef, Korean-style marinated beef and one — no, two — orders of tripe. The waiter’s still scribbling as he walks away.

“We should have tried the liver too!” Hefter says. We think he’s kidding. It’s the last time we’ll make that mistake.

For the last eight years, Hefter, 39, has been traveling to Japan for inspiration, bringing culinary ideas to his restaurants back home. He tries to make his annual trip during the sakura zensen, cherry blossom season. Late March is a joyous time in Japan; it represents the beginning of spring, a time not just for walking in parks and through lanes to view the blossoms, but also for savoring the candied pink flowers and the tender green leaves, along with sweet cherry salmon and young spears of bamboo and the fragrant purple buds of the shiso plant.

Six days in Japan with Hefter and his wife, Sharon — and his insatiable appetite and curiosity — is also a crash course in sushi, tempura, yakiniku and kaiseki, culinary styles that define Japanese dining but are rarely seen in their pure form, even in Los Angeles.

First course: yakiniku

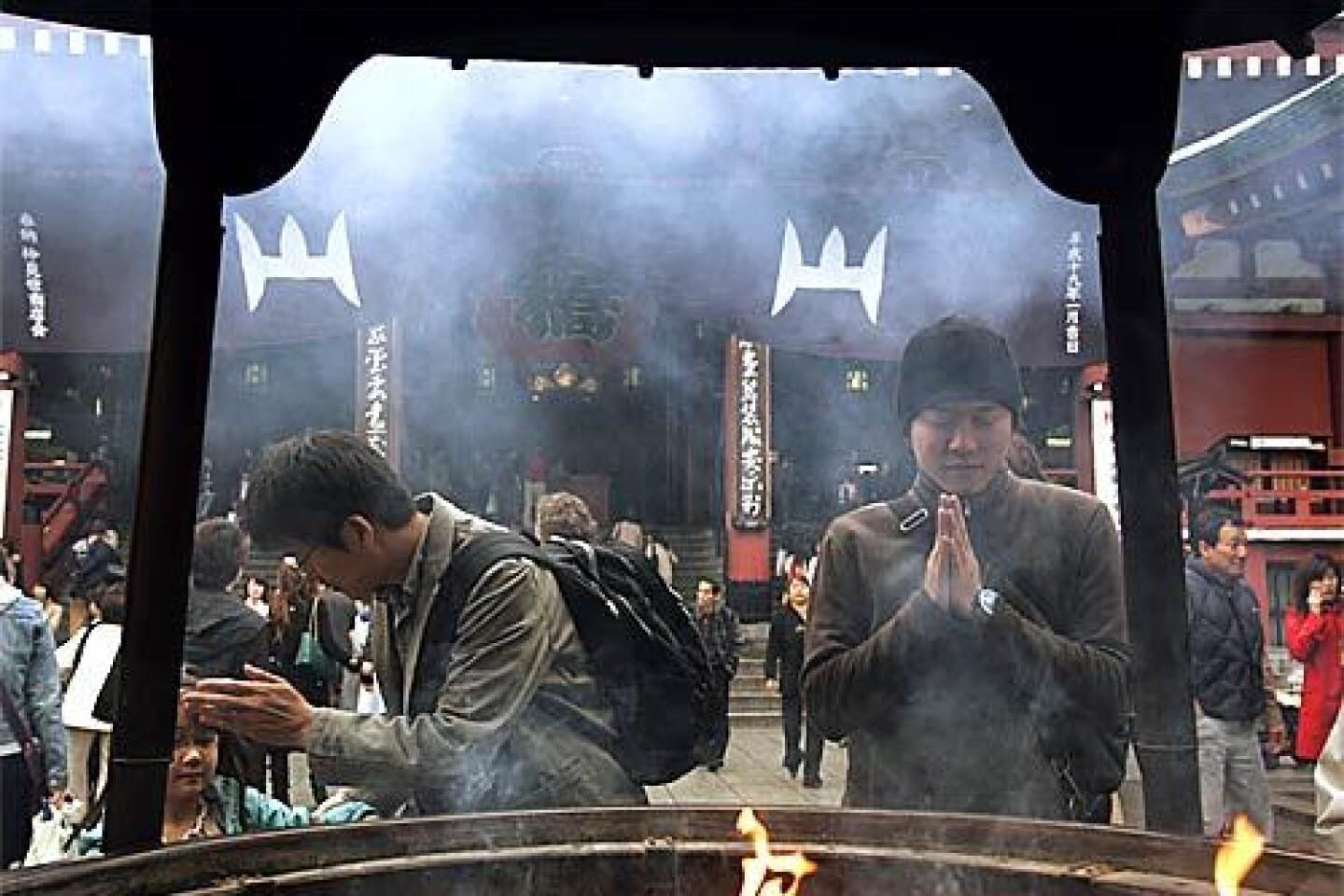

Most travelers to Japan are content to visit the Ginza and the temples and the Harajuku district. They might ride the bullet train or climb Mt. Fuji. But to explore Japan through its food is to experience something very deep about the culture.

Whether it’s Tokyo or Kyoto or points in between, food is an obsession here. Everywhere you look, there are sushi bars, soba stands, yakitori bars, French pastry shops, tofu specialists, shabu-shabu joints. There are tonkatsu-ya, the restaurants specializing in deep-fried pork cutlets; tamago shops, where they sell nothing but sweetened omelets; even unagi-ya, freshwater eel restaurants. Rows of vending machines line alleyways, offering 10 kinds of tea, both hot and cold.

Some places are for eating on the run — like the noisy ramen stands where you stand and slurp. Others are incredibly formal — perfectly quiet and almost spiritual, like the kaiseki restaurants where the country’s best chefs practice their art.

Soak it all in for a few days, and it’s easy to understand why this is the place Hefter returns to year after year for rejuvenation and inspiration. “It stimulates the creative process,” he says. “I let it digest for a month and then go back to my notes and get inspired again.”

Hefter plots out his trips with extreme precision. He gets tips from other chefs, often Nobu Matsuhisa and Masa Takayama. He talks with chefs in Japan and with hotel concierges. He checks Zagat, and a Japanese food website, www.bento.com, and cross-references it all. “It’s a lot of work,” he says. “And then you can’t always get into the restaurant.”

It will come as no surprise to anyone who’s dined at Cut, Hefter’s white-hot steakhouse in Beverly Hills, that on this trip, he starts with beef.

We’ve all heard about Kobe beef, but Kobe is just one of hundreds of types of artisanal beef in Japan. There are 41 prefectures that raise Wagyu cattle and produce their own amazingly tender, incredibly marbled, meticulously graded beef that winds up in restaurants such as Aragawa, where one steak can set you back $1,400. It was there, on an earlier trip, that Hefter found the inspiration for the innovative combination of ultra-high temperature and wood smoke he uses to cook the steaks at Cut.

Tonight, Hefter, dressed in jeans, wants to go casual and check out a spot for yakiniku — the Japanese version of Korean barbecue. The restaurant, Shotai-en, is relatively inexpensive. Tonight’s tab will come to about $30 a person. And Hefter has ordered a lot.

Almost instantly, the beef starts coming to the table. Hefter takes charge, dabbing slivers of sashimi with chile paste and slivered onion, and passing them around. It looks good, but it’s hard not to hesitate. How often do you pop a slice of raw beef into your mouth?

“You only live once!” says Hefter. It will be one of his mantras during this trip. And so ... it’s astonishing — cool and subtle, just one velvety bite. Perfect.

Hefter turns to the tartare.

“OK if I do the mixing?” he says, breaking the yolk and working it into the meat. He scoops a big spoonful onto each sheet of nori, slips in a shiso leaf and folds it into a cone. He makes one for each of us, and we don’t hesitate this time. There is the crunch of the nori against the creamy shock of the meat — as rich as toro, the fatty tuna belly that’s prized here, flavored with soy and sesame, and luxuriously smooth. It is the most sensual thing we have ever eaten, and it’s gone in two unforgettable bites.

As we recover, a waiter pulls a hammered copper chimney down from the ceiling, an exhaust fan starts to whir, and then another waiter brings a cast-iron grill pot piled with glowing red bincho — a charcoal made from Ubamegashi oak that adds a distinctive smoky flavor.

“I’ll tell you, I’m not doing the cooking,” Hefter says, reaching for the vegetables despite himself.

First, he puts the onions on the grill, then shishito peppers, carrots, mushrooms. And the leeks — the long Tokyo negi that are everywhere in spring, even sold as souvenirs in train stations. Taste and you understand: Left whole and grilled, they turn into something like melting little sausages. Next come the shrimp, other meats and — the star of the show — a platter of Wagyu: three kinds, each more marbled than the last.

We wander back out into the night. It’s 11:30 p.m., and the Ginza is a blazing postcard, quiet except for a few circling taxis and a cluster or two of wanderers like ourselves. We’ve all been up for about 27 hours straight, and it’s time to head back to Roppongi Hills, the Grand Hyatt and a soft bed. Hefter is glad one of his sous-chefs, Tetsuro Yahagi, will soon be joining the party. Comfortable as he is, he’ll be relieved to have a Japanese speaker onboard.

Second course: sushi

The Tsukiji Market is the world’s largest fish market — 2,000 tons of fish move through here each day, six days a week. It’s the best place to visit if you want to understand why a Japanese sushi restaurant is a travel destination unto itself. If it swims, it’s here — turtles, eels, clams, spiny lobsters, shrimp, skinny silvery needlefish, crabs, abalone, little firefly squid with googly eyes, octopus and stalls filled with dozens of kinds of uni, the bright sea urchin roe, the best of which looks like slices of ripe apricot.

And, of course, tuna: Tsukiji’s tuna auction draws fishermen from around the world. Here they can fetch the highest price, and at dawn, the auction is in full swing. The turnover is constant — as one row of enormous tunas, steam rising from their icy skins, is sold, another is moved in. Motorized flatbeds, bringing ever more fish, almost run over swarms of tourists and buyers — this is where the city’s sushi chefs shop.

On this trip, Hefter will eat sushi only once: at Sushidokoro Shimizu, an eight-seat sushi bar that has Tokyo buzzing. After a little wandering through a drizzle in the Shinbashi district, one of the old parts of the city, we find Shimizu in a narrow alley, amid apartment doorways and houseplants set out in the rain. We announce ourselves and are told to wait outside. At last a few diners emerge and we squeeze in — there’s not an inch of extra space. Eight stools, a smooth pale counter, and behind it, the formidable Kunihiro Shimizu.

Shimizu stands with an enormous copper grater, preparing wasabi paste. Is it OK if a photographer takes pictures? He nods yes. He rules his space without a word. An assistant brings out the rice, a gorgeous rosy color, and begins gently fanning to cool it.

Shimizu starts preparing giant squid, scoring and crosshatching the flesh. There is time to notice the differences from American sushi bars: no long list of fish to choose from; Shimizu serves only seafood in season. No glass case between you and the chef; it’s designed to look as though you’re eating in his home. As much attention is paid to the rice as to the fish; it is seasoned with a good dose of kasuzu vinegar, and the grains are so flavorful that different varieties are used to complement different fish. And there are no crazy sushi rolls; actually, there are no rolls at all.

Shimizu presents the squid, then maguro, the lean tuna belly, and chu-toro, the fattier belly. His big hands handle the sushi more than you usually see, squeezing and rotating each piece. There’s kohada, a spring specialty, the lightly picked Japanese shad, salted and marinated in vinegar, and needlefish that looks like a sparkling silver chain.

Suddenly, the action stops. Shimizu gets a terrible, dark look. At last, he speaks — and he’s not happy: Taking pictures of the food is OK, but not of the chef. We’re clearly on the verge of being thrown out.

Eyeing us, Shimizu slowly continues, picking up hamaguri, a reddish braised clam, then gives us salmon roe so fresh it’s like eating sea foam, sea urchin that’s shockingly pure and clean. Somewhere around the anago — salty, sweet saltwater eel, so tender it’s almost melting — he warms up. Clearly, we’re appreciating his work; he seems to decide we’re OK. A conversation begins, and by the end of the meal, he’s posing for pictures with Hefter.

Third course: tempura

When foodies rave about the great food halls of the world — Harrods in London, Fauchon in Paris, KaDeWe in Berlin — they rarely carry on about Tokyo. But the basement of the Takashimaya department store houses one of the most awesome displays in the world.

Bread and pastry boutiques from France, salumi from Italy and Germany, acres of Japanese specialty foods, green tea so fresh it looks like just-cut grass, curry stands, pickle vendors, fresh noodles flavored with seaweed — and everything there for the tasting.

But it’s the produce that gets the most reverence, displayed like fine jewelry. Here are the famous $80 muskmelons, a ribbon attached to their T-shaped stems, the $7 apples and the Kumamoto shio tomatoes, so crisp and sweet, you might actually spring for a $100 box. The bamboo shoots, freshly unearthed. The negi leeks, bundled like lily flowers.

Cooking veggies like these requires the hand of an artist. Hefter knows the man: Fumio Kondo, tempura chef extraordinaire. “It’s amazing how many people go through life thinking they’ve had tempura,” Hefter says, with pity.

Kondo, the chef’s tempura bar in the Ginza, has only a dozen seats. This chef couldn’t be more different from the sushi chef. He’s calm and good-natured, wearing an expression somewhere between melancholy and bemused. And he doesn’t mind having his picture taken.

He prepares everything before our eyes — whisking the batter, quickly dipping the fish or vegetables into it, and dropping them into the hot oil. Kondo lays the tempura on sheets of paper on our trays. Prawns, succulent and sweet, the crust perfect and fragile; fat pieces of asparagus; half-moons of lotus root; kisu, a small, delicate white fish from Tokyo Bay; taranome, a mountain vegetable that looks like a tiny bunch of celery and has a wonderful, barely bitter taste.

“You can tell the guy’s a master at what he does. He really attacks it like an art,” says Hefter. He loves its lightness. The batter is thin, “just a coating to protect it while it’s frying. He lets the ingredients shine through.”

Hefter asks whether baby eels might be available. He had sampled them here before and was bowled over. Kondo smiles and nods, and, ah, here they are: each a tad wider than a strand of spaghetti, bundled with a shiso leaf and fried. Absolutely spectacular. Hefter’s in heaven.

Fourth course: kaiseki

Kaiseki is the haute cuisine of Japan, the ultimate expression of the reverence for ingredients, the respect for nature and the seasons, the skill of the chef and the art of dining itself.

The meal takes place in a hushed tatami room, traditionally with just one table and a luxurious sense of space and attention. Each course has its own visual language, not only in the artistic arrangement of the food itself, but also in the porcelain and lacquers chosen to hold it — often, these pieces are precious antiques.

The framework is formal: 14 courses that always include two artfully composed appetizers, a sashimi course, a simmered dish, a grilled dish, a steamed course, a middle course that always comes in a beautiful lidded dish.

The ingredients are just as defined: Kaiseki chefs cook only what is in season, and the “seasons” change every two weeks. That means, at the end of March, they are all cooking young bamboo, harvested the moment it sprouts; cherry salmon caught off the coast of the Sea of Japan; the slightly bitter sprigs called mountain vegetables; and, of course, the cherry blossoms and leaves.

Kaiseki is what Hefter mostly wants to eat. “It’s a dying art,” he explains, like all forms of haute cuisine.

So, we follow him one afternoon down a flight of stairs on a Ginza side street to Uchiyama, his current favorite. Hefter booked a reservation six weeks in advance and felt lucky to get it.

Although there’s a tatami room, Hefter prefers to eat at the counter. Here, you can see the chef at work as he places the food before you, instructs you on how to eat it and watches your reactions.

Lunch begins with a cube sesame tofu, its powdery white skin concealing a creamy, warm center; a dish as beautiful as a still-life, of eggplant, firefly squid, sea urchin and miso; and sashimi presented with sprigs of shiso. Hefter tears the tiny purple flowers from the branch and they softly drift over the fish, perfectly evocative of the drifts of cherry blossoms outside.

Savory mochi comes wrapped in a cherry leaf, in a bowl of thick dashi broth with bamboo and a cherry blossom. We bite into the leaf, and it tastes intensely of cherry — we can taste the wood, the fruit, the leaf in this single bite. Buried inside the mochi is creamy, explosively flavored sea urchin.

“This kind of cooking, a lot of foreigners never see,” says Hefter. And it’s the one that inspires him most.

Kaiseki’s birthplace is Kyoto, and so off we go, hopping the bullet train south. It’s a sprawling city, with skyscrapers on one street and low, wooden buildings on the next. The Kamo River cuts through the center, and along its banks are the old geisha districts, still filled with clubs and restaurants.

If there’s any doubt that Kyoto is as food gaga as Tokyo, it’s put to rest as we walk along Pontocho Alley, a narrow stone-paved lane. Tucked between the ochayas — the wooden teahouses where geishas entertain — are all manner of eating and drinking places.

Umbrellas open, we cross the Shijo-Ohashi Bridge to Gion, the city’s most famous geisha district, passing a rice cracker shop on one corner, with dozens of pretty snacks displayed in glass cases. We wander into a pickle shop; inside, a geisha is pickle shopping. There are at least 100 types of nicely packaged pickles, each with a dish for tasting.

At Tousuiro, a casual restaurant overlooking the river, we have a tofu riff on a kaiseki lunch — tofu made into a custard, tofu glazed with miso, tofu grilled on a stick, tofu in a croquette with sea eel. But most impressive is the first course, brought in wooden pots called oke that look like redwood hot tubs. We spoon the fresh tofu into small bowlfuls of broth, sip, talk, watch the river outside the window. It’s deeply peaceful, and finally, we absorb that truth about kaiseki too.

When we leave, the chef follows us out of the restaurant and bows; we bow back. He stands in the door as we walk down the narrow, residential street. It’s raining, and we keep looking back.

And he keeps bowing, and we bow back.

brenner@latimes.com, michalene.busico@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.