Ultra athletes chase their own limits

SUBHED: The goal is always over the horizon for the band of endurance junkies who thrive on such races as triple, quadruple and even quintuple triathlons.

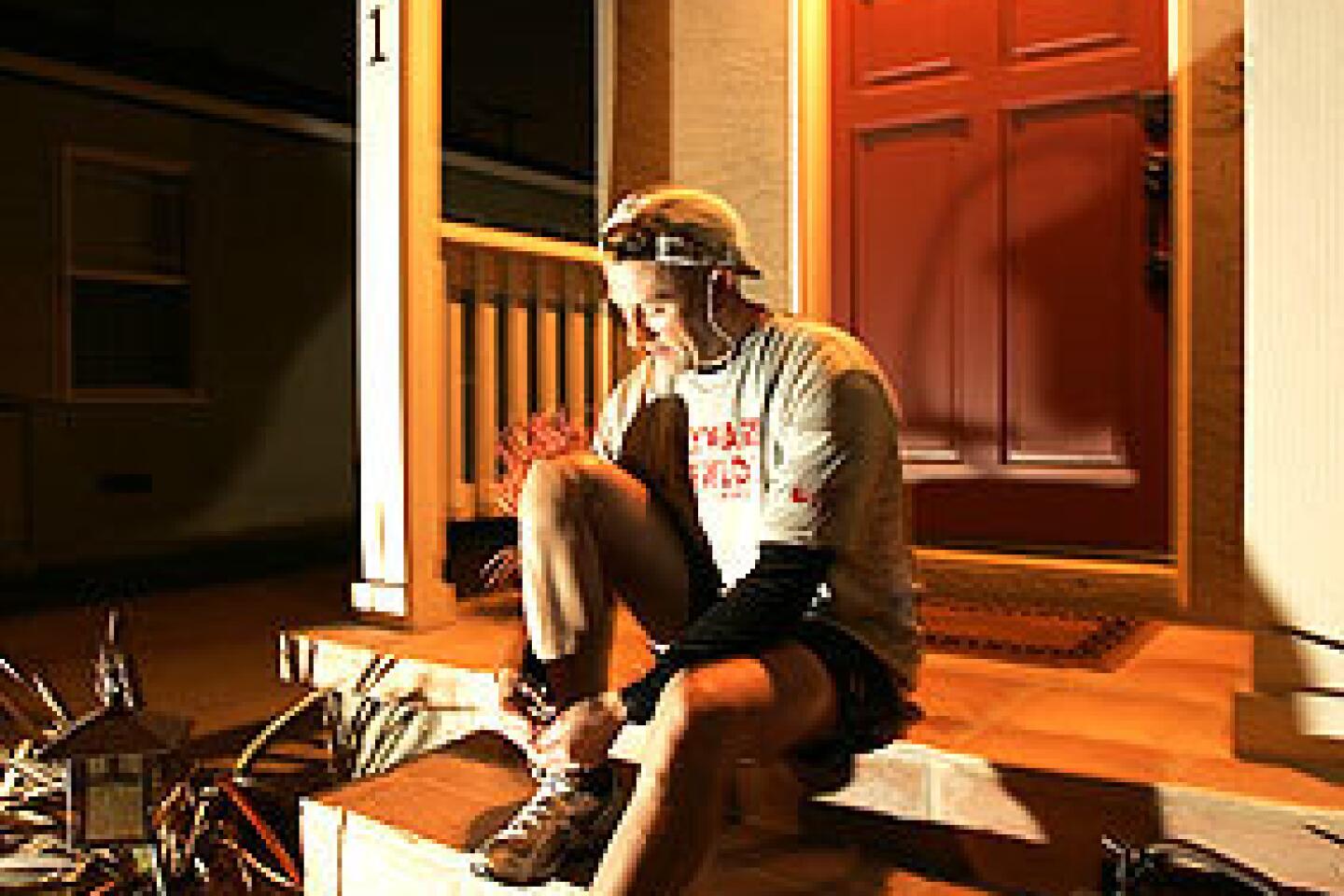

On the surface, Todd Zagurski seems the definition of ordinary. He collects art and pens, draws a regular paycheck as a vice president of a transportation company and lives in a one-story home in Long Beach with his wife and cat.

But a few times a year, he takes part in bike races that last 24 hours, 50-kilometer runs and quintuple triathlons that go on for days. (That’s a 2.4-mile swim, 112-mile bike ride and 26.2-mile run — times five.)

In a race, out there alone, “you feel more alive than you do at any other moment,” the 42-year-old says. “You really have to pull everything together for one of these things, physically and mentally.”

And in that, he may be normal — for an ultra competitor.

Participants in extreme endurance events push themselves beyond what seems possible — running, swimming and biking for seemingly endless hours through deserts or snow-covered valleys — all for the satisfaction of knowing they raised the bar higher than they had before. And sailed over it.

By persevering, sport psychologists say, these competitors are seeking the excitement, the unexpected moments, that have been leached out of our 9-to-5 lives. “This is another way for us to challenge ourselves physically that we don’t get through other interactions,” says Trent Petrie, director of the Center for Sport Psychology at the University of North Texas.

A need for these challenges has grown, judging by the increasing number of people who are signing up for ultra races. The Western States Endurance Run, a 100-mile run through the Western States Trail in Northern California, is one of the oldest 100-mile runs, dating back to the mid-1970s. Race director Greg Soderlund says last year saw a 20% jump in applications, twice the steady 10% growth over the years. Ten years ago there were a handful of 100-mile runs; Soderlund estimates there are now about 40. Add to that the growing number of über-competitions such as deca-triathlons, cycling marathons and runs through exotic locales such as the Antarctic, the Amazon and Death Valley.

Though ultra race athletes have some things in common (competition, testing oneself) with those who do single marathons and triathlons, their raison d’etre is setting higher and loftier goals, and setting very few limits. What ultra competitors aren’t, they say, is crazy — a label often cast upon them by people who can’t fathom what they do.

*

One goal follows another

For ultra racers, the goals are — put simply — ever-more-difficult challenges.“Oftentimes someone will start with a 10K, they’ll have some success there, their confidence builds, and they might challenge themselves more,” Petrie says. “For some, that might be running a little faster. For others, it’s pushing themselves to run a marathon, or do three in a year.”

Ultimately, he says, “when you reach your goal, you ask yourself, what do I want to do next?”

In the case of Zagurski and other ultra competitors, next means outdoing your last triumph, while simultaneously hunting for a harder one — running 50 kilometers through the desert, then 100. Or doing a double triathlon, followed by a triple. And maybe two triples in close proximity.

Not only are extreme athletes self-motivated, they’re also problem solvers. “It’s along the lines of, I have to get my body from here to there in one piece,” whether that’s through the desert or frozen tundra, says Kristen Dieffenbach, a sport psychology consultant and assistant professor of athletic coaching education at West Virginia University, who’s also an ultra and adventure racer.

That mental ordeal adds another dimension to just how far the body, and mind, can be pushed. “It’s the constant new challenge. In a 5K,” she adds, “you might get a blister.”

Ultra events take athletes far out of the urban environment and into the unknown. Races through mountain areas put runners in remote places most hikers never see as they climb higher and higher elevations on rough, rocky terrain that’s sometimes unmarked. Ice cakes on their face as they endure sub-zero weather running through the barren Antarctic, and they sweat buckets in the Sahara, where temperatures can reach 120 degrees. During multi-day races, hallucinations are not unheard of as sleep deprivation grabs hold.

Time spent alone is part of the appeal for many competitors. Although some ultra athletes prefer to train in groups, many spend the long, arduous hours of preparation by themselves. Then there’s the race itself, where mile after mile is done solo.

“I think they like the solitude,” says Ken Hamada, race director of the Angeles Crest 100-mile Endurance Run and himself a former ultra competitor until knee problems curtailed his racing days 10 years ago. “It’s just quiet, and I think that’s the appeal. It’s not like 10,000 people are running this thing.”

Those stretches of isolation provide plenty of mind-clearing opportunity. During the training and the events, Zagurski says, his mind wanders from one subject to the next, perhaps his next meal or what he should get his wife for her birthday. Such mental respite, he says, helps him recharge.

That’s not to say competitions are Zen-like excursions. Ultra racers occasionally hit rough patches that can threaten to derail a race: swollen limbs, bruised feet, severe dehydration, debilitating muscle pain, crippling fatigue.

Yet the often excruciating aspects of these events can help bring about a sort of epiphany, says Richard Donovan, race director for the Antarctic 100K ultra race — 100 kilometers in the Antarctic — and an ultra competitor himself.

“The first time I did the Marathon des Sables (a 250-kilometer race across the Sahara), I went in not having a clue about what I was getting into,” he says. “And after a few days of being worn down, your body is shot, and things become quite simple. All your outside worries go away. You reach a trough, and then immediately after that, there’s a sense of elation, where things make sense.”

The small pool of athletes in this relatively new and somewhat unknown niche makes research difficult in areas such as how ultra competitors persevere and what motivates them beyond a single marathon or triathlon. But that, Dieffenbach predicts, will change in the next decade or so. “A lot of people are becoming more interested in the psychological side of these endeavors.”

*

Early competitiveness

Zagurski’s path to ultra races began when he was a teenager growing up on Mercer Island in Washington state. Already an accomplished competitive swimmer, he took up bicycling and, as he puts it, “started hitting benchmarks — 50 miles, 75 miles, 100.” At 15 he took off for a weeklong road trip with friends; the next summer he went for a month. At 16 he did his first 24-hour cycling marathon and completed 200 miles.“Within a day of that,” Zagurski recalls, “I thought, shoot, if I did 200 miles, I want to do 300. The next year I went back and rode 308.”

He did his first single triathlon in Santa Rosa in 2000 and was surprised to find it wasn’t as difficult as he thought, so he figured he’d try two a year. Frustrated at not being able to get into the legendary Ironman in Kona, Hawaii, he decided to try something harder, and did a double triathlon in Virginia in 2004. In spite of some stomach problems during the race, he finished third out of about 12. Soon after, he decided to do a triple (which he ended up not finishing after he crashed his bike), then a quintuple, which he did finish. Also on his ultra resume are some Alcatraz swims, a couple of 50-kilometer trail runs and a long list of single marathons and triathlons, which he considers warmups for longer races.

Zagurski’s race schedule this year includes two single triathlons and the Ultraman Canada, a 10-kilometer swim, 418.3-kilometer bike race and 84.3-kilometer run. He’ll also do a triple triathlon, followed by a quintuple. His training regimen off-season includes an hour of something predawn Monday through Friday, be it a run, swim, bike or gym workout. On the weekends he’ll go for six or seven hours. During the season, he’ll keep the same schedule weekdays but on weekends will intensify the training to 12 to 14 hours, again splitting it between the three triathlon disciplines.

Zagurski keeps chasing the rare but spectacular moments that occur in the almost physically impossible. He recounts, for example, the last day of the quintuple triathlon in Mexico, on which he woke from scant hours of sleep, knowing he would finish. “No one else was out yet, and it was a great feeling because you realized that within reason, there’s nothing you can’t do.” While racing, he says, “There are a handful of times when things went really well, and you wait for that to happen again, but it’s worth it just to see it one more time. You’re always waiting for that perfect race, and maybe it’s never going to happen, but at least you’ve got to try.”

Unfinished events — like the triple triathlon — gnaw at Zagurski, even though he’s surpassed the distance in a quintuple tri. “There’s always that tendency to not be happy with what you just did,” he says. “I think a lot of people finish and they’re content, and I’m just not.”

Competing gives him the confidence to face other hurdles — like public speaking. “I’m a terrible public speaker,” he says, “but I get through it.”

Few ultra athletes are in their 20s or even 30s; the majority, like Zagurski, are 40 and older, with the means to afford the travel and expensive fees (sometimes in the thousands) and the time to devote to training and racing. The desire to compete is still powerful. Some are also at a time in their lives when they’re looking for more than boats and bling to make them happy.

“Some folks have been following the good life, and part of that feels really good, but it doesn’t necessarily bring long-lasting happiness,” says Charlie Brown, a North Carolina-based sport psychologist and spokesman for the Assn. for the Advancement of Applied Sport Psychology. When you use your strengths and resources in pursuit of something that is meaningful, then you tend to be happy while you’re doing it.”

For Zagurski, conquering problems in a race spills over to his daily life: “You encounter roadblocks all the time, and how you get around them is important,” he says. “Oftentimes the solution is very easy, or it just takes a little perseverance. I think people give up too easily.”

There are few places he won’t consider going. The 135-mile Badwater race from Death Valley to Mt. Whitney? “It has some intrigue.” The Antarctic? “I’d give it a shot.”

Zagurski clearly lives to push himself and craves the feeling of accomplishing a particularly difficult feat that he can mentally tick off on his endurance race to-do list. He says he can’t imagine living any other way: “What am I supposed to do, walk up and down the mall?” he says. It’s a desire that hasn’t dimmed and won’t, he hopes, for some time. “I remember getting back from [the quintuple triathlon] in Mexico and I was out in the yard working, and I felt so good it was unbelievable. I was 40 then, and I thought gosh, I just finished a quintuple triathlon, and I feel fantastic. Maybe some day I’ll have to slow down, but I sure hope not.”

*

jeannine.stein@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.