‘We’ll do Whitney, right?’

Blame everything on the rains of last winter. Without them I would never have realized that I was losing my son.

It’s an odd thought, but there I was last June trying to cross Mehrten Creek in Sequoia National Park, wondering whether this two-day High Sierra trek I’d undertaken with Jarrod was such a good idea. It was the first backpacking trip for either of us. He’d been wanting to do it for years, and now that he was 16, I felt the time was right. But that didn’t make it any easier.

Carrying a 30-pound pack while walking uphill was harder and more painful than I’d expected, and balancing it across a dashing tumult of water, nearly impossible. My feet were killing me too. Though my boots were broken in, they were about half a size too small.

So after one sudden slip into the creek, Jarrod helped me up from the rocks, and we plotted how we might get across. I changed my hiking boots for Teva sandals, threw my pack to the other side and waded through the knee-deep snow melt. Jarrod tossed over his pack next, and I lobbed him my sandals, five sizes too small, which he wedged onto his feet and then plowed through.

Our initial plan had been to go to Pear Lake, but that path, along with just about every other choice in the region, was closed due to late-season snow and ice. The ranger in the Wilderness Office suggested the High Sierra Trail, one we’d never before hiked. “Use caution with the high and fast creek crossings,” she’d noted on the permit.

We’d left Jarrod’s younger siblings and dad back at the Lodgepole campground and set out with a map and compass, sleeping bag and food in our packs. If we stayed on this trail long enough — 71 miles — we’d eventually make it to Mt. Whitney. That’s what Jarrod would have liked — he being a rambunctious teenager — but I’d talked him into something more reasonable: Bear Paw Meadow, 11-plus miles along the well-marked trail, and back again.

“But in September,” he had to announce as we made our way, snow-topped peaks to our right and massive pines to our left, “we’ll do Whitney, right?”

A friend of ours, a ranger in the parks, had mentioned that he’d have some time off later in the summer.

“September, right?” became the refrain.

We’d set out on the solstice. The sun’s journey across the sky was about to shorten, day by day. I don’t know if I realized it at the time, but I was in the same position with my son.

My influence over him was about to wane. Later that summer, he would leave for a six-week stay in Michigan to study music, his first major venture away from home. In two years, he’d be packing for college.

As he walked the path ahead of me, his poorly attached sleeping bag at the bottom of his pack swaying sloppily with each step, the words of Kahlil Gibran came to mind: “You may house their bodies but not their souls, / For their souls dwell in the house of tomorrow, which you cannot visit, even in your dreams.”

A small bear, perhaps a yearling, rustled by a mile or so later, taking scant notice of us. A striped snake startled us, passing within inches of Jarrod’s Converse.

“Red to yellow, kill a fellow,” he calmly recited the poem he’d learned. “Red to black, venom lack .It’s OK, Mom,” he reassured me. “It’s fine.”

This is what it’s all about, I thought. Teaching him, so he can teach me.

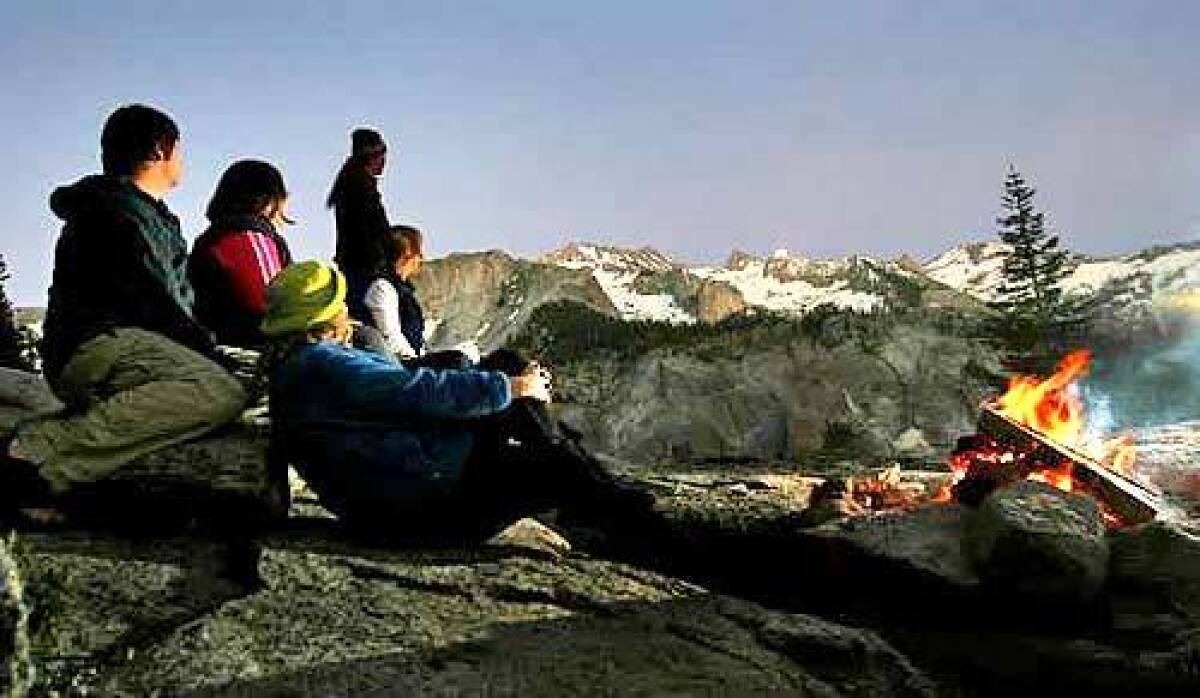

What seemed like miles — and miles — later, we hit snow. Near 4 p.m., bone tired, we made camp. Jarrod pitched the tent. We made a fire and put our camp kettle right next to the burning embers to boil water for dinner and drinking water for the next day. As the daylight began to change, we doused the flames and headed up a rocky peak to watch the sun’s goodbye passage on the last gloriously long day of the year.

We sat on a massive outcropping facing the snow-encrusted Western Divide as the sun sank behind us, painting the ice and rocks purple and pink. We spoke little, waiting for the moon to rise. It took longer than I’d expected, but once risen, it lit up the entire forest. I reached up and mussed his hair.

Back in our tent during the night, my hulking son asleep next to me, I watched that ridiculously bright moon through the bug netting, the pine trees swaying above. A sound like horses galloping made my chest tighten as two deer passed near where we lay.

I may not have taught him all he’ll need to navigate his life, but I’ve taught him enough to get us this far.

The next day, sore and achy, we were ready to move on. We hiked homeward, and when tiredness overtook us, we shouted lines of absurdist poetry, and then we quieted and hiked in silence, passing the trail mix back and forth.

“But in September” — Jarrod tried not to betray his own exhaustion — “we’ll do Whitney, right?”

“We’ll see,” I simply said.

As it turned out, he didn’t get to Whitney; he had to be in school. But he’s shooting for next summer. Today, that’s hardly the point.

Whitney, I know now, is a part of his future, the house of tomorrow where his soul dwells, a place I will never visit, not even in my dreams. Or, at least, not until I buy boots that fit.

Bernadette Murphy is author of “Zen and the Art of Knitting.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.