Along the Missouri with Lewis and Clark

The smell of wood smoke and burning sage filled the lean-to. Rain pounded the roof. Soggy clothing hung helter-skelter overhead, and river mud coated the floor.

Still, the mood was magical. All eyes watched our camp cook, Tony Kellar, who is part Creek Indian, as he read aloud from “The Lakota Way: Stories and Lessons for Living,” a book of Native American wisdom. The story was a parable about humility, which we would all learn by the end of our kayak trip.

Tony finished reading, and our eyes turned to Robin Morgan, a 30-year-old Lakota Sioux. “All my life, I have wanted to journey on the great Missouri River,” Robin said. “Sharing this journey with family of the first white men to explore this region brings the experience full circle.”

On this June night, our last together on the upper Missouri River in north-central Montana, we — six kayakers and four river guides — had been joined for the evening by brothers David and Jason Lewis and their three children. They claim to be descendants of Meriwether Lewis, who, along with William Clark, had plied these same waters 200 years ago, during the first official U.S. overland expedition to the Pacific Northwest.

I had wanted to make my own “Voyage of Discovery” to mark the bicentennial of the Lewis and Clark trip. Initially, I considered a 2,000-mile trip down the length of the Missouri, in a reverse, or west-to-east, re-creation of their expedition.

But after meeting 25-year-old Chad Caldwell, who owns and runs Missouri River Expeditions, I was convinced I would get an authentic Lewis and Clark experience on a shorter, more manageable kayak trip down the river, traveling nine days from Fort Benton to the Fred Robinson Bridge. This 149-mile stretch of the Missouri is designated a national wild and scenic river, and the landscape has changed little from the spring of 1805, when Lewis and Clark traversed the area.

The river carries with it the stories of Native Americans like Nez Percé Chief Joseph, of outlaws like Kid Curry and of the homesteaders and trappers and explorers who helped shape the character of the West.

If I could find six to eight kayakers who shared my delight in that history, Chad would line up support staff. My wife, Colleen, signed up immediately, even though she had camped only once before. Next, we recruited my sister-in-law, Mary Beth McGraw, and her teenage son, Matt, from St. Louis; Bernice Kuca, from Boston; and Jeff Smith and his son-in-law Jamie Burnett, both from Minneapolis.

We convened in Great Falls, almost 199 years to the day when Lewis, Clark and their crew manhandled their boats around the cataract.

Under a weeping sky the next morning, Chad led our soggy band to a put-in west of Fort Benton. There we began what would become a daily struggle: trying to maintain our footing in slick Missouri River mud while stowing our gear in the kayaks.

The crew — Tony, his teenage son, T.J., and Robin — loaded four coolers and 15 boxes of food and wine into kayaks and a canoe. As I slogged down the bank with my own gear, Colleen stood looking down the Missouri’s gray waters, pondering the days ahead.

“Bring my stuff back,” she suddenly yelled down to me. “I’m going home.”

After 26 years together, I knew her too well to force the issue. She set off for our Kansas home.

*

The journey begins

Tony led us in a paddling tutorial. “Keep your nose over your belly button and you can’t tip,” he said reassuringly.Before our launch, we joined hands, and Chad read an Indian prayer for our safe passage. “Spirits of the water accept my sacrifice draw us not down to our death in your cold, dark realm; cast us not upon the rock hidden by the foaming.”

Then we climbed into our fiberglass ocean kayaks, crammed with sleeping bags, tents and personal gear, and set off down the wild Missouri.

As we cleared the Fort Benton Bridge, the mist lifted briefly, and a flock of white pelicans did a slow flyby, the birds tipping their wings as if to salute us. A pair of bald eagles eyed us suspiciously. A beaver slid down the banks and then disappeared into its lodge.

They were but a few of the more than 230 species of birds, 60 types of mammals and 20 varieties of amphibians and reptiles that populate Montana’s upper Missouri River. Two centuries ago, Clark noted the “great numbers of the Big horned animals” — the explorers’ first sightings of bighorn sheep.

T.J. and I paddled together in front, and the rest fell into place behind us. Tony, with the supply canoe, brought up the rear. The only sounds were the slap, slap of paddles against water and the occasional whoosh of wings as hundreds of swallows swept the river’s surface of mayflies.

The sun soon appeared, and we enjoyed our first unfettered view. Flowing east to northeasterly here, the Missouri cuts through canyons nearly 1,000 feet high, exposing sedimentary and igneous rocks 55 million to 90 million years old. The result is a spectacular landscape of dramatic rock columns and multicolored sandstone tables, much of it unchanged from Lewis and Clark’s first sight of it.

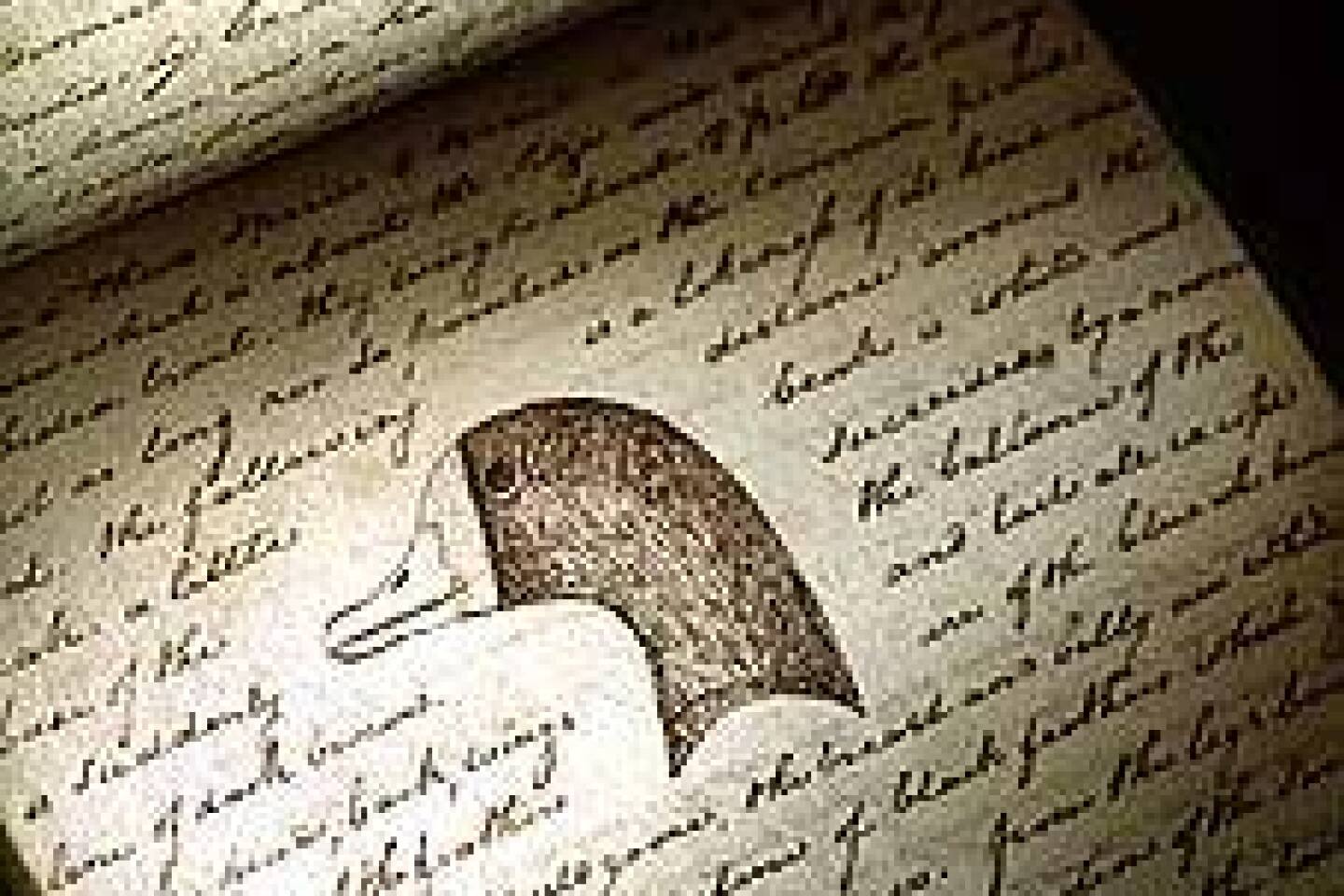

“The hills and river Clifts which we passed today exhibit a most romantic appearance. The bluffs rise to the hight of from 2 to 300 feet formed of remarkable white sandstone woarn it into a thousand grotesque figures .” Lewis wrote on May 31, 1805. (Spelling was apparently not their forte.)

We pitched camp that first night amid a knee-high stand of wild mustard on a deserted sandbar nine miles shy of the Missouri’s confluence with the Marias River, which Lewis named for his cousin Maria Wood. The expedition had lingered here because, as Lewis wrote on June 3, 1805, “An interesting question was now to be determined; which of these rivers was the Missouri.”

After beaching my kayak, I practically fell into my tent in exhaustion, only to be rousted half an hour later by Tony’s shouts of “Come and get it! Cheese quesadillas!” I picked my way down the slippery path and sank my teeth into probably the best appetizer I had ever tasted. Then, playing bartender, I poured martinis and settled into a camp chair to await Tony’s main course: a tasty chicken spedini.

I finished the evening with a cigar and cognac, listening to the first of Tony’s readings under the stars.

That feeling of ease was doused by a steady, cold drizzle the next day as we set off for the mouth of the Marias. Just before noon, we pulled into a small takeout past the Loma Bridge and held a hasty conference about that evening’s destination. We had been paddling well, so we decided to press on an additional 21 miles for the comfort of Virgelle Mercantile’s heated cabins at Coal Banks Landing.

The wind picked up, blowing spray and flume into our faces, and turned what should have been a four-hour paddle into a six-hour one. Exhausted, we arrived at the landing around 6:30 p.m. I took a much-needed shower in Virgelle’s converted icehouse, which served as the communal bathroom for the six-cabin complex. I unpacked my wet clothes and strung them all around the tiny cabin, built in 1914 and first occupied by homesteader Dan Mosier. It felt like a luxury hotel.

We dawdled until noon the next day, not wanting to give up modern pleasures to battle the wind-whipped waves. Our goal was to paddle 13 miles to a Bureau of Land Management camp by Eagle Creek.

But after two hours, we had gone only four miles. The wind strengthened, blowing about 30 mph. We staggered into camp four hours later, too tired to say or do much.

“This old river can take it out of you,” Chad said in his gravelly voice.

Eagle Creek had sheltered Lewis and Clark too, on May 31, 1805, and Lewis described the scene in his journal: “As we passed on it seemed as if those seens of visionary inchantment would never have an end; for here it is too that nature presents to the view of the traveler vast ranges of walls of tolerable workmanship, so perfect indeed are those walls that I should have thought that nature had attempted here to rival the human art of masonry had I not recollected that she had first began her work.”

We spent two nights here, exploring both sides of the river, climbing rocks, swimming and bathing in the muddy Missouri. We found pictographs, evidence of the area’s early inhabitants.

Late in the afternoon of our second day, we had our first — and only — encounter with a rattlesnake, which Tony scooped out of our path with a long stick.

*

Cribbage along the river

Several days of rain had turned the complexion of the river chocolate. After our two-day respite, we faced a 21-mile paddle under another dreary sky. We had to keep telling ourselves that we were in it for the experience.We paused for a lunch of hot buffalo chili and tortilla chips, then pressed on toward the Missouri’s meeting with the Slaughter River, so named by explorers because they discovered “a vast many mangled carcases of Buffalow” that had been driven off a 120-foot precipice by Indians who needed their meat and hides.

No such horrors greeted us when we arrived at the Slaughter, only simple lean-tos, fire rings, hewn-log seating and clean toilets.

During the evening, Robin and I discovered we shared a love of cribbage, and we played the first of nearly 50 games on the journey.

We squeezed in a few more games the next morning before setting out for Judith Landing.

Bernice, Matt, Mary Beth, Jeff and Jamie left us here to return home, and while Chad and his crew drove them to Great Falls, I stayed behind, with a BLM ranger for company.

The guides returned the next morning with Kathy Young, from St. Paul, Minn., who planned to kayak the final 61 miles with us.

She had optimum conditions for her first day out: The wind was at our backs and the sky was robin’s-egg blue. We paddled five hours at a good clip and camped at an unmarked river bend in an area of plentiful firewood and limestone bluffs. That evening, we introduced Kathy to our nightly ritual of Native American readings.

These carried a special poignancy at our last camp beside the Missouri, Woodhawk Bottom. Nearby, Chief Joseph and 200 to 300 warriors with their wives and children crossed the Missouri in an attempt to flee to Canada, pursued by the U.S. Army. Chief Joseph surrendered on Oct. 5, 1877, at Bear Paw, Mont., only 40 miles from the border. The Nez Percé were sent to a reservation in what became Oklahoma, where many died.

As the campfire flickered and shadows danced, we listened as Tony read the chief’s words:

“I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed .It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food . Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.”

My journey too had come to an end. The next morning, as I jogged up a rutted dirt access road, I paused to look back at the river valley below me. The Missouri stretched like a silver ribbon far into the distance.

Ours was more than a vacation. It was a voyage of discovery, in which we learned as much about ourselves as we did about the explorers in whose wake we paddled.

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Paddling the wild Missouri

GETTING THERE:

From LAX, Delta, Northwest, United and Alaska offer connecting service (change of plane) to Great Falls, Mont. Restricted round-trip fares begin at $298.

OUTFITTERS:

Missouri River Expeditions, P.O. Box 536, Vermillion, SD 57069; (866) US-KAYAK (875-2925), https://www.missriverexp.com . We chose this company owned and operated by Chad Caldwell. This year, it will offer a Lewis trip similar to mine July 1-6, paddling 108 miles, for $1,500 per person, including meals, shuttles, boats and gear, and one night in a cabin at Virgelle Mercantile.

Missouri River Canoe Co., 7485 Virgelle Ferry Road North, Loma, MT 59460; (800) 426-2926, vwww.paddlemontana.com. Don Sorensen and Jimmy Griffin have served as outfitters on Missouri River trips for more than 20 years. We stayed in their cabins at Virgelle Mercantile. Equipped and guided kayak or canoe trips run about $325 per person, per day. Rates for the restored cabins are $40 per person, per night, including a continental breakfast. Rooms in the Mercantile’s B&B start at $95 a night.

Montana River Outfitters, 923 10th Ave. North, Great Falls, MT 59401; (800) 800-8218, https://www.montanariveroutfitters.com . Guided three-day trips from $595 to $795 per person, including boats, meals and camping equipment but not sleeping bags or clothing.

Bureau of Land Management, P.O. Box 11389, Fort Benton, MT 59442; (406) 622-3839, https://www.mt.blm.gov/ldo provides a list of licensed river guides and outfitters. It also sells a set of two waterproof maps of the river, for $4 each, that are invaluable companions on the Missouri, and sends a free information packet on request. (Note: As of the Travel section’s deadline Tuesday, the website was down for maintenance.)

ESSENTIALS:

The float season runs Memorial Day to Labor Day. June and July tend to be wetter months. The fall can provide spectacular paddling and less-crowded conditions.

Be prepared to rough it. There are limited takeout points and access to emergency services.

Besides the list your outfitter provides, take quick-dry clothing, water shoes and plenty of waterproof bags. Protect your camera gear in dry bags, watertight housings or both. Take a good insect repellent.

TO LEARN MORE:

Travel Montana, 301 S. Park Ave., Helena, MT 59620; (800) 847-4868, https://www.visitmt.com .

“Undaunted Courage” by Stephen E. Ambrose. An excellent overview of the Lewis and Clark expedition.

“Montana’s Wild & Scenic Upper Missouri River” by Glenn Monahan, and Chanler Biggs, Northern Rocky Mountains Books, 315 W. 4th St., Anaconda, MT 59711; (406) 563-2770. An excellent mile-by-mile guide to the river.

— Craig Ligibel

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.