From the Archives: For one summer, L.A. set up an ‘urban campground’ for the homeless. No one called it a success.

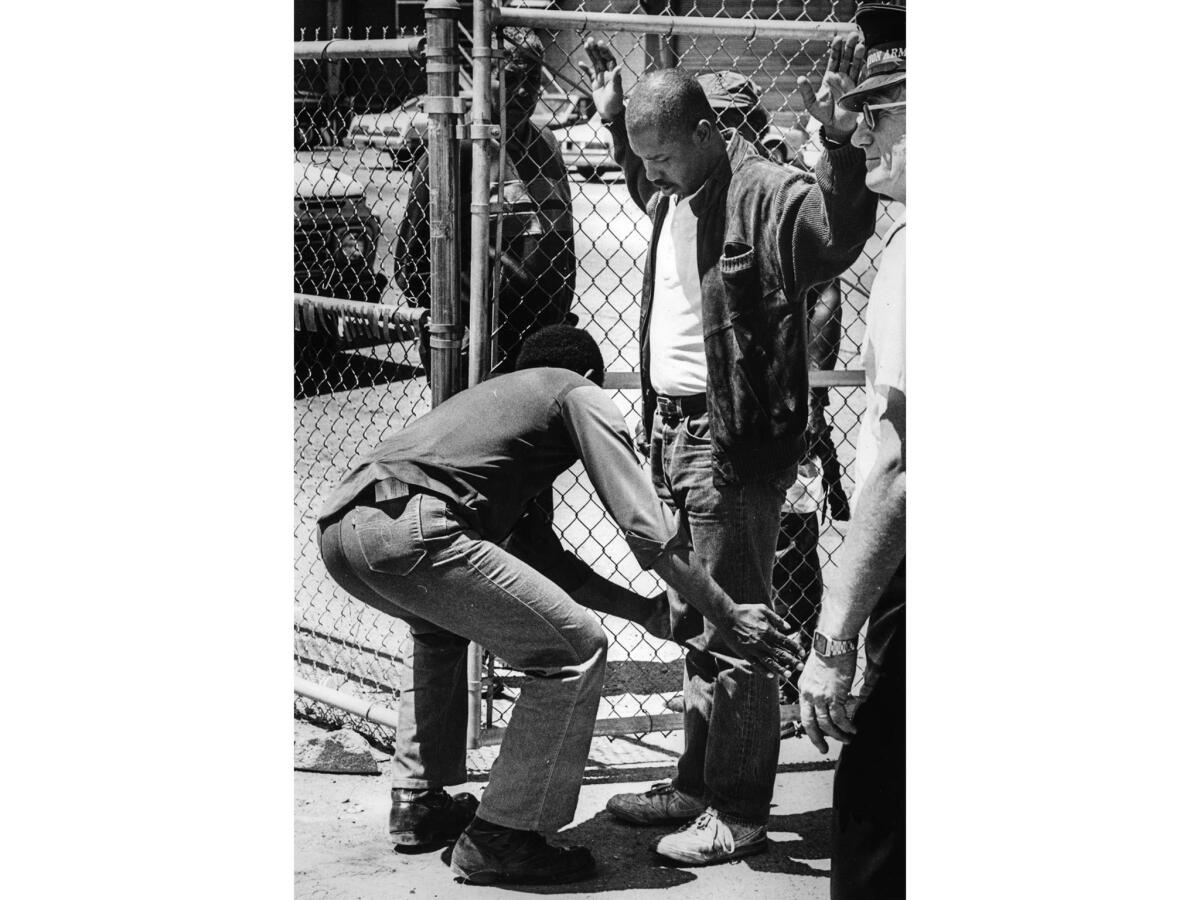

In 1987, the Los Angeles Police Department embarked on a major crackdown on homeless encampments on skid row. In response, Mayor Tom Bradley proposed a temporary site to relocate the homeless.

In a June, 4, 1987, Los Angeles Times article, Penelope McMillan and Roxanne Arnold reported:

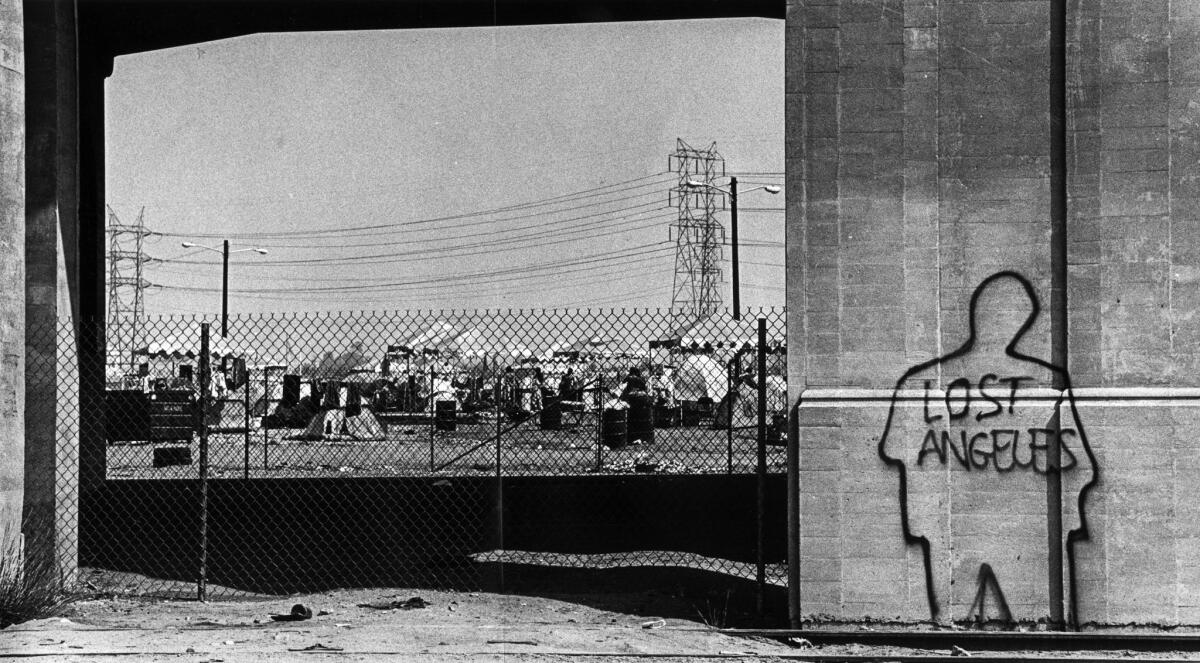

In an effort to supply short-term housing for residents of sidewalk encampments on Skid Row who face a police crackdown starting today, Mayor Tom Bradley proposed Wednesday a temporary "urban campground" on vacant land downtown near the Los Angeles River.

"This is a shelter we think will offer another housing alternative for those who are in need," Bradley said of the proposed campground, which would be operated for two months on 12 acres of Southern California Rapid Transit District land at 4th Place and Santa Fe Avenue.

The camp, which Bradley said could accommodate "600 people or more," would be operated by the Salvation Army. The Community Redevelopment Agency would fence the property, provide portable toilets, water and lighting, he added. …

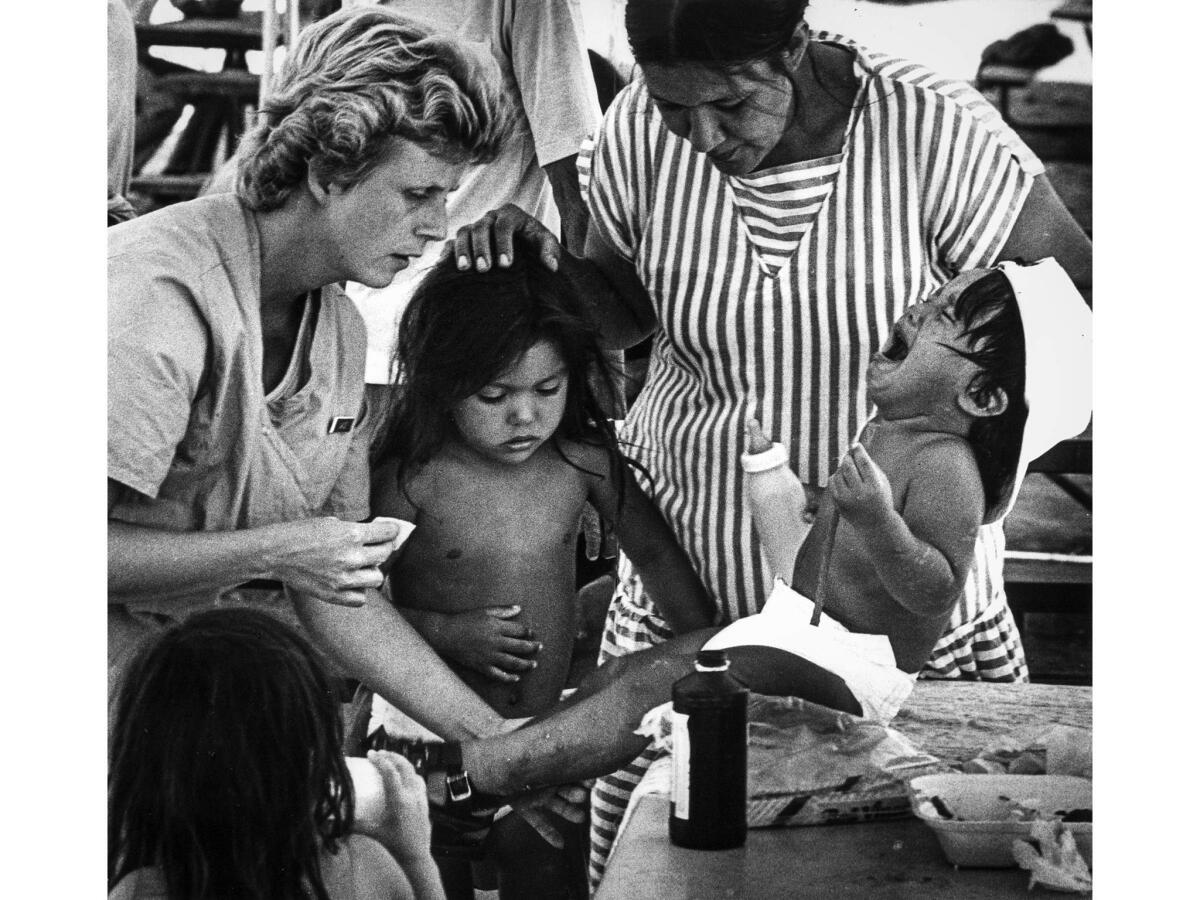

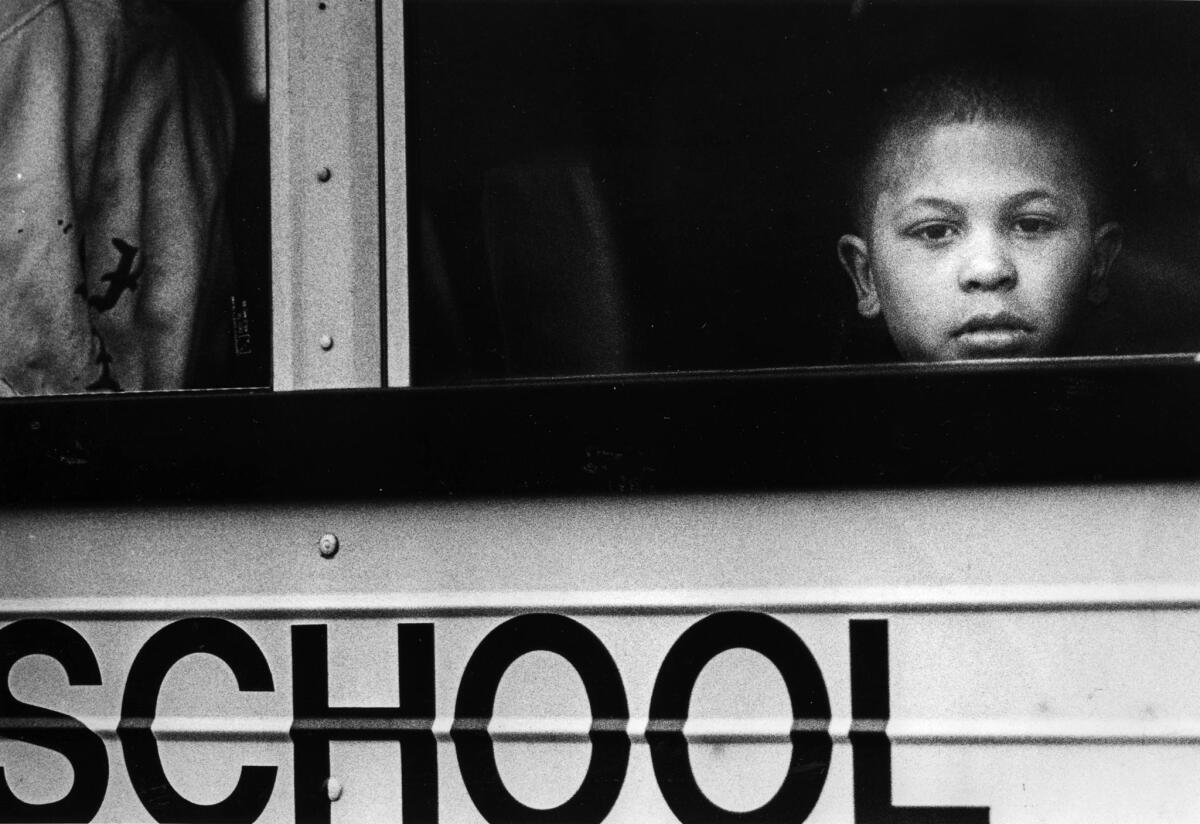

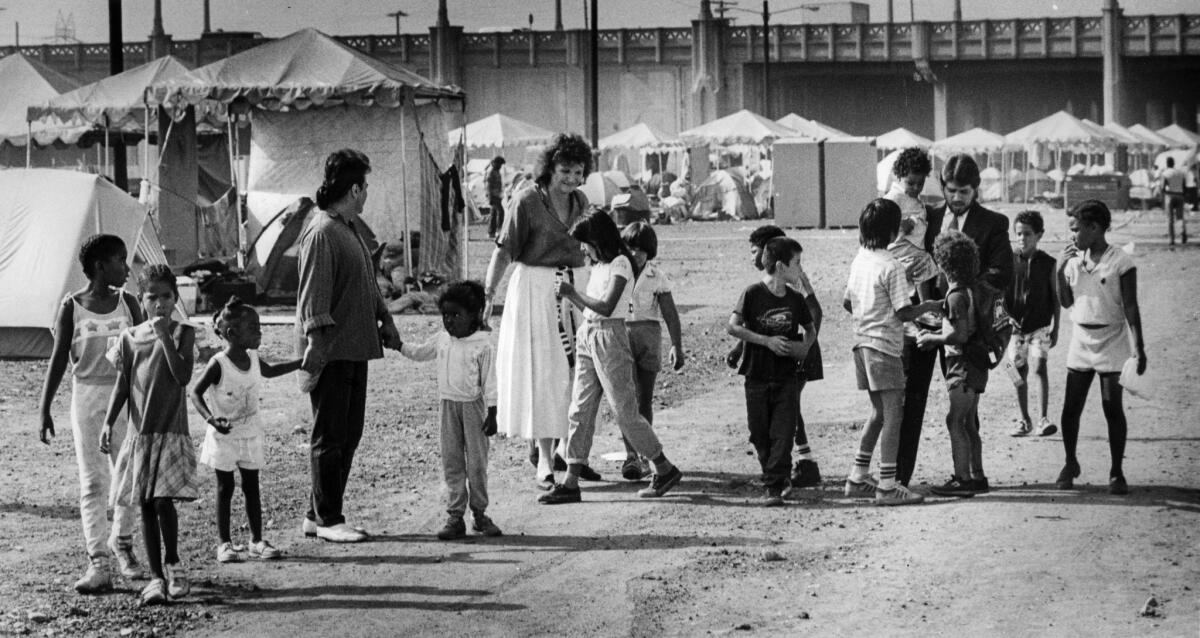

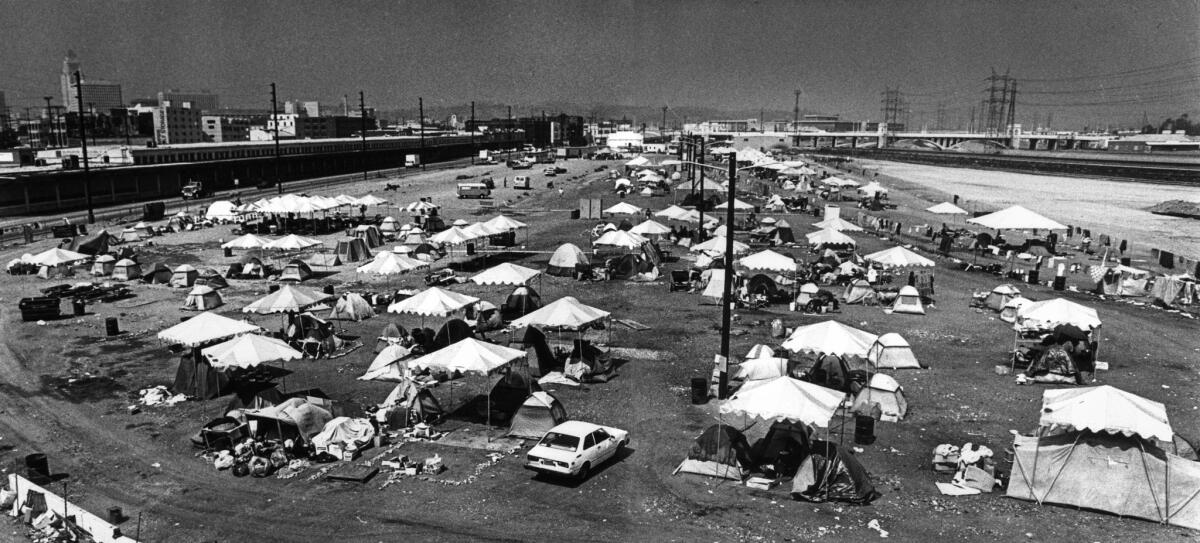

On June 15, 1987, the urban campground opened. Within two weeks, about 500 homeless were at the site. Social service agencies sought to help. Schooling and daycare were provided for the children.

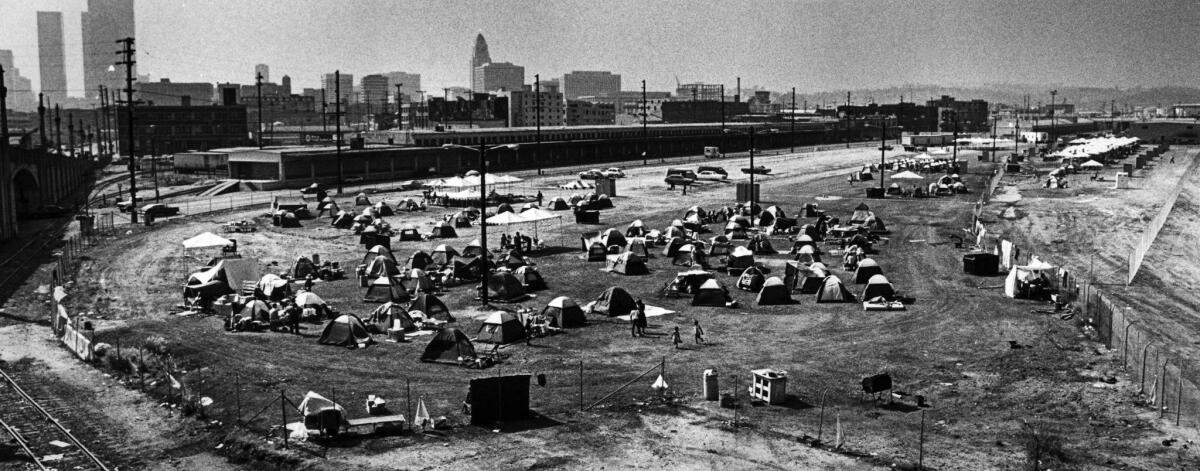

But the site was temporary – it closed on Sept. 25, 1987.

The headline for a McMillan article in the Sept. 25, 1987, Los Angeles Times summed up the results:

Homeless Camp Ends Much Like It Began : A Grim Place of Refuge Closes Today — and No One Involved Calls It a Success

From McMillan's article:

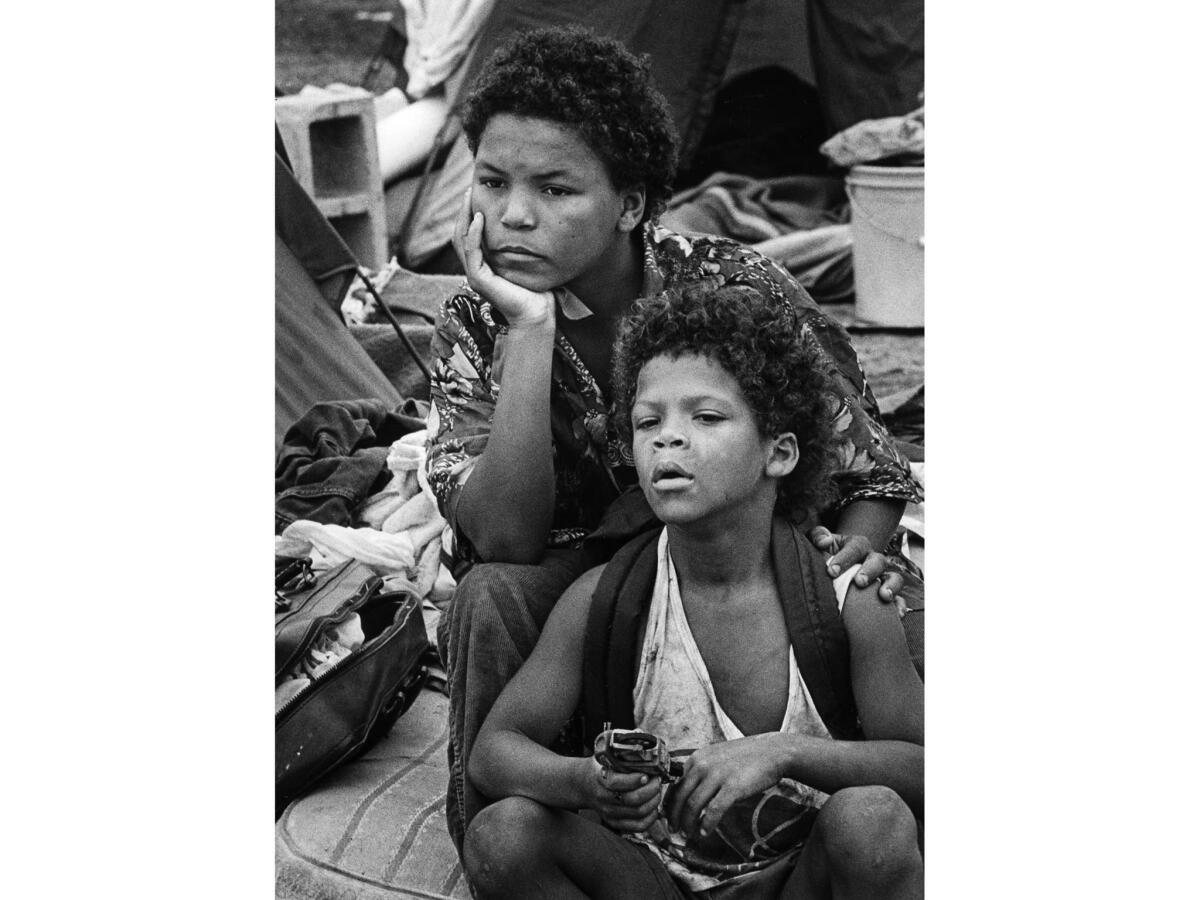

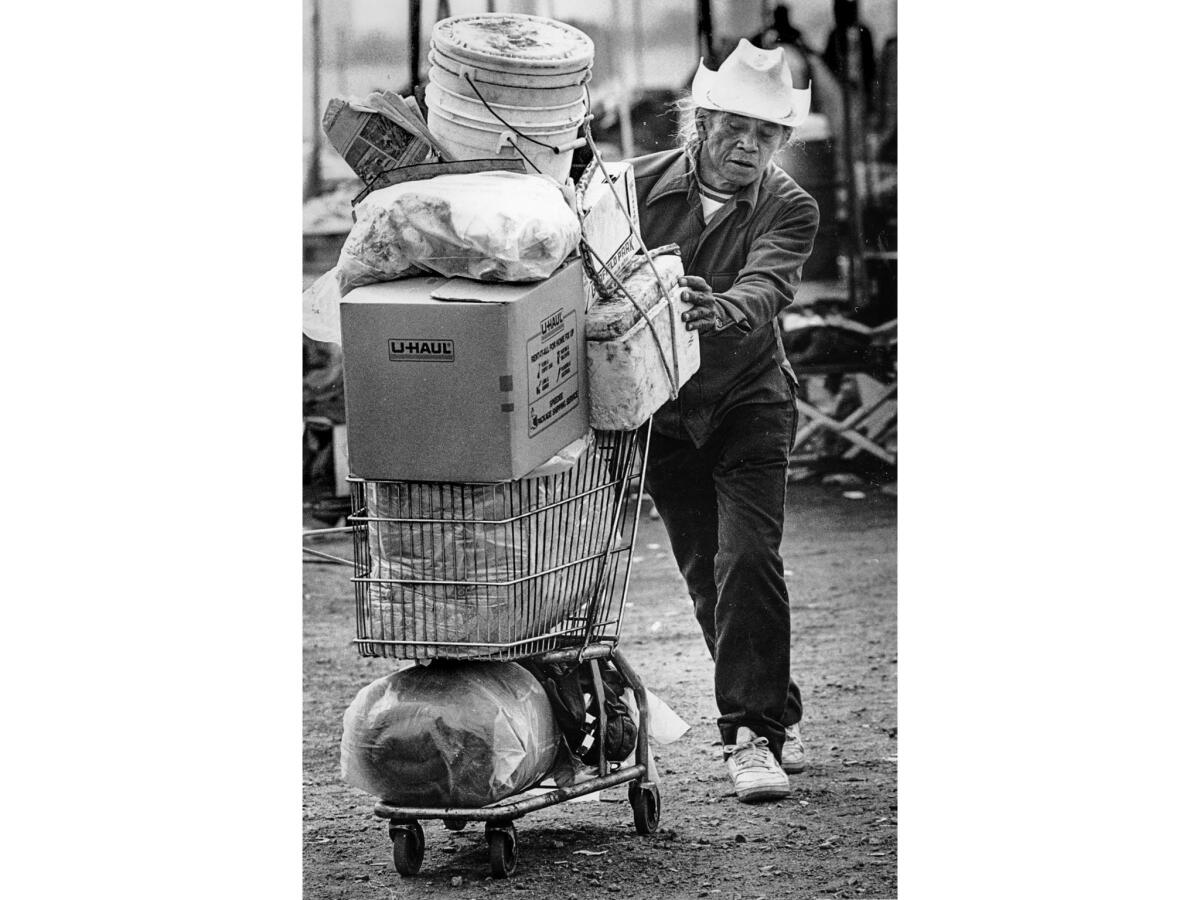

It was ugly to begin with, a flat stretch of land flanking the Los Angeles River, fenced and then filled up with trailers, canopies, hundreds of cots and tents. Then came the people, 2,600 in all, who said they had no other place to go.

It is still ugly as it ends, a grim, dusty refuge for 236 people who say they still will have no other place to go when the camp is shut down at 5 p.m. today.

The City of Los Angeles' urban campground for the homeless has been, as Maj. William Mulch of the Salvation Army put it, "a desperate attempt to help very desperate people.”

No one calls the attempt a success--not the city, the Salvation Army or advocates for the homeless.

The city's ambition when it opened the camp June 15 was to temporarily shelter the homeless, provide social services and help them find work. The camp did shelter people, in the most minimal way, and several services were set up.

But officials noted that only a small percentage availed themselves of the services, and the vast majority of the homeless who passed through the campground apparently left no better off than when they came.

After 103 days and $397,000 in city costs, Deputy Mayor Grace Davis said the camp left city officials convinced "we should not be in the shelter business." …

The Salvation Army, which incurred $227,000 in costs of its own in running the camp for the city, leaves with its reputation as a friend of the needy tarnished.

“'We never thought the Salvation Army would be involved in something like this.' I've had that said to me," Lt. Col. David P. Riley, the army's Southern California division commander, said.

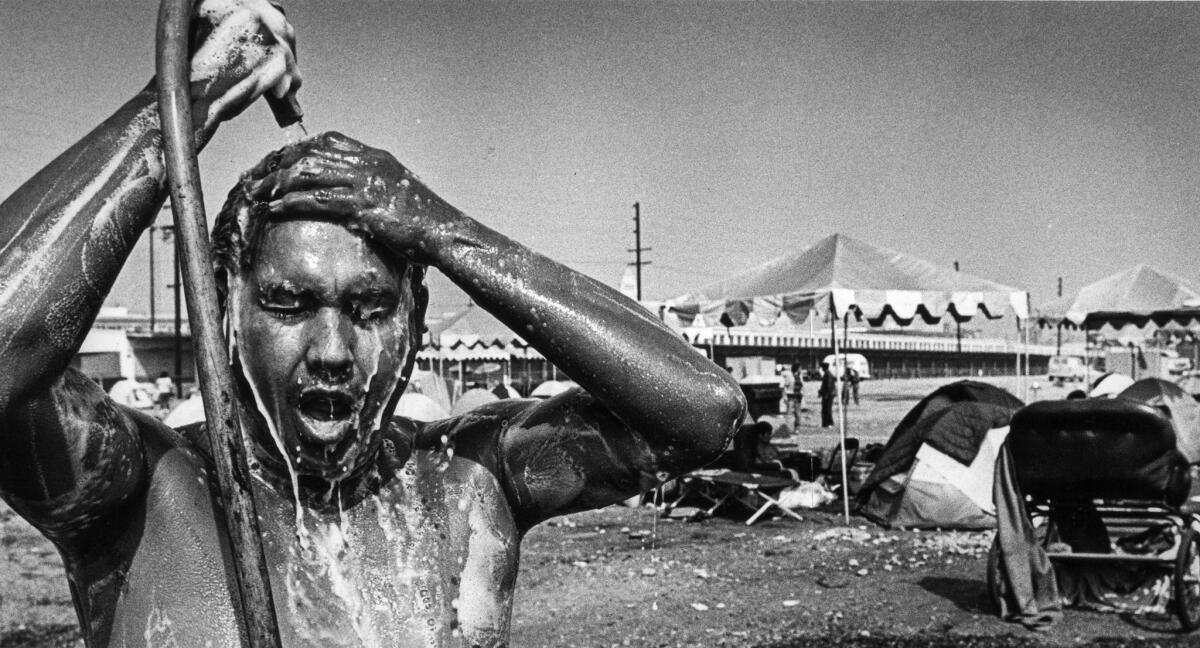

"There was the dust in the air all the time, lack of drainage of the water, showers that leaked from the day they were installed," Riley continued. "The equipment was not adequate. There was no way you could bring dignity or cleanliness to it."

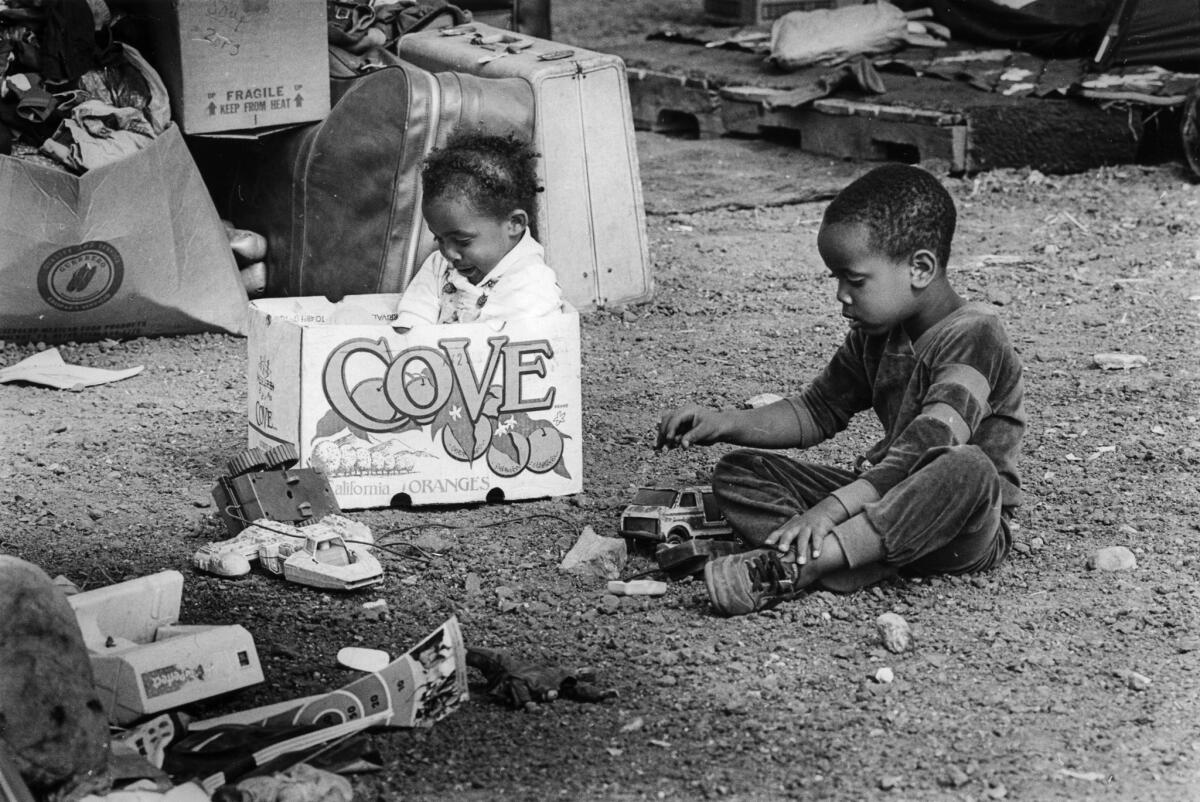

"The campground was unsanitary, unhealthy and a bad environment for children," said Jack Faz, social services coordinator for Para Los Niños, the service agency that shouldered most of the burden of relocating 119 families with 265 children, 75% of whom came from within Los Angeles County. "It was a bad thing all around."

Yet, it did give a small number — 240 of the 2,600 homeless who passed through -- a leg up with help to find jobs. "I couldn't have done that on the street," said 22-year-old Raymond Byfield, who now has a $640-a-month job driving a truck. It also helped more than 100 people obtain legal identification, which employers must require under new immigration laws.

"A lot of people learned to live collectively and to share," David Bryant, a homeless leader, said. "For a lot of people, there was a real sense of community they hadn't had."

This post was originally published on Dec. 20, 2016.