Rights report details threats to journalists in Afghanistan

Afraid of losing his radio show, Aqel Mohammad Waqar refused to tell anyone about the threatening calls and messages he received for his unvarnished reports on the conflict in Afghanistan.

The 19-year-old had only been with Spinghar Radio in his native Nangarhar province in eastern Afghanistan for two years and worried that discussing the threats publicly would endanger him further or cost him his job.

By the time his employers found out he was at risk, it was too late.

On Jan. 16, unidentified gunmen shot Waqar and two family members after they returned from a wedding to their home in the village of Hajian. His death made him the first Afghan journalist to be killed in 2015.

According to a new Human Rights Watch report released Wednesday, his case illustrates the growing number of dangers faced by Afghan journalists. Eight journalists were killed in 2014, a 63% increase from the previous year.

The sources of the danger are manifold, the group said. They include government officials bullying reporters and editors into not covering controversial topics, Taliban insurgents threatening violence to force favorable reporting, and law enforcement officials letting assaults and killings go unpunished.

“Afghan journalists face threats from all sides,” the group said in the 45-page report.

Although no group claimed responsibility for Waqar’s death, Sher Bahadur Hemat, his boss at Spinghar Radio, said his critiques of the Taliban — which has been active in his area for years — would have made him a target of the insurgents.

“Aside from Taliban, there was no one else who could have done it. He had no enemies,” Hemat said.

After an attack on a Kabul high school late last year, the Taliban for the first time placed Afghan journalists directly in their cross hairs, warning that they would target any media, civil society or other organizations that attend or publish “anti-Islam programs.”

But its not just the armed opposition that the media must fear, according to the Human Rights Wach report, which detailed several cases of intimidation or violence by government officials and Afghan security forces.

Last year, Ehsanullah Amiri, an Afghan journalist for the Wall Street Journal, was blindfolded and detained by the National Directorate of Security, the Afghan intelligence agency, for several hours after he took mobile phone pictures at the site of a bombing in Kabul.

Human Rights Watch says the threats have prompted many Afghan journalists, editors and media directors to carry out self-censorship, shying away from investigative reporting or stories that could anger powerful interests.

“There are many issues we have purposely stayed away from,” said Abdul Matin Amiri, a journalist in the southern province of Kandahar.

Abdullah Azada Khenjani, news director for 1TV, a private television station, said government officials and allied strongmen often use their influence to put pressure on the media.

After a recent report by his channel on the smuggling of lapis lazuli in the northern province of Badakshan, Khenjani thought the Afghan government would launch an investigation into a lawmaker implicated in the illegal trade.

“Instead, the [member of parliament] took advantage of his connections to the ministry of information and culture to launch a campaign against 1TV,” he said. “Now we, not the MP, are the ones facing investigation.”

There is increasing hostility between police and journalists in volatile southern Afghanistan, Amiri said, with officials often refusing to provide details for basic news reports on violence in rural areas.

“The bigger danger is simply in the lack of information,” said Amiri. “Officials just won’t cooperate with you. Sometimes they will even say outright, ‘We were told not to speak to the media.’”

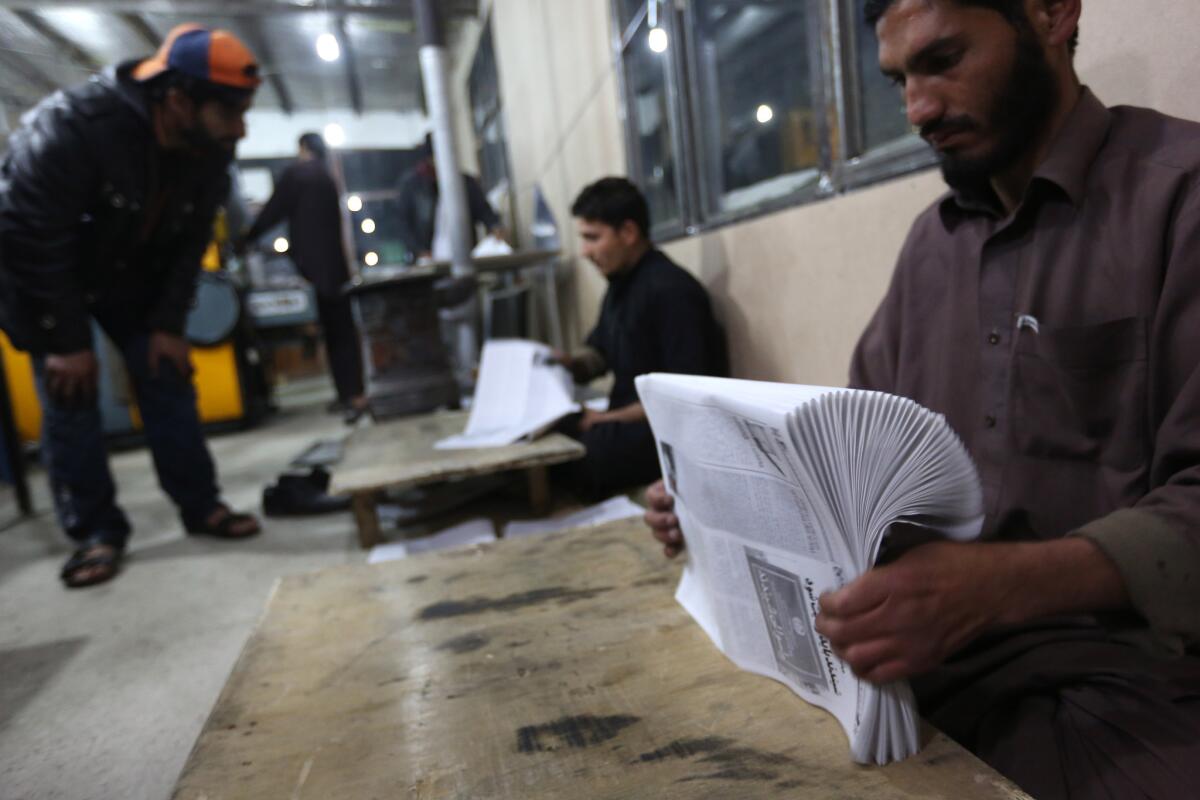

The climate of violence, intimidation and self-censorship has marred a private media industry that has otherwise flourished in the 14 years since the U.S.-led military invasion toppled the Taliban government.

More than 1,000 news organizations currently operate in Afghanistan, up from about 15 during the Taliban years preceding the 2001 invasion. But Khenjani said that in a country where officials and strongmen can exert influence over the government, the media in Afghanistan lack the popular support needed to thrive.

“In other countries when the media report on corruption or violence against children there will be widespread calls for the government to take action, but we have yet to see even one example of public outcry to our reporting,” he said. “Without that, it becomes increasingly difficult for us to continue to report on important social and political matters.”

Latifi is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.