Congo’s president is about to lose his mandate, but refuses to step down

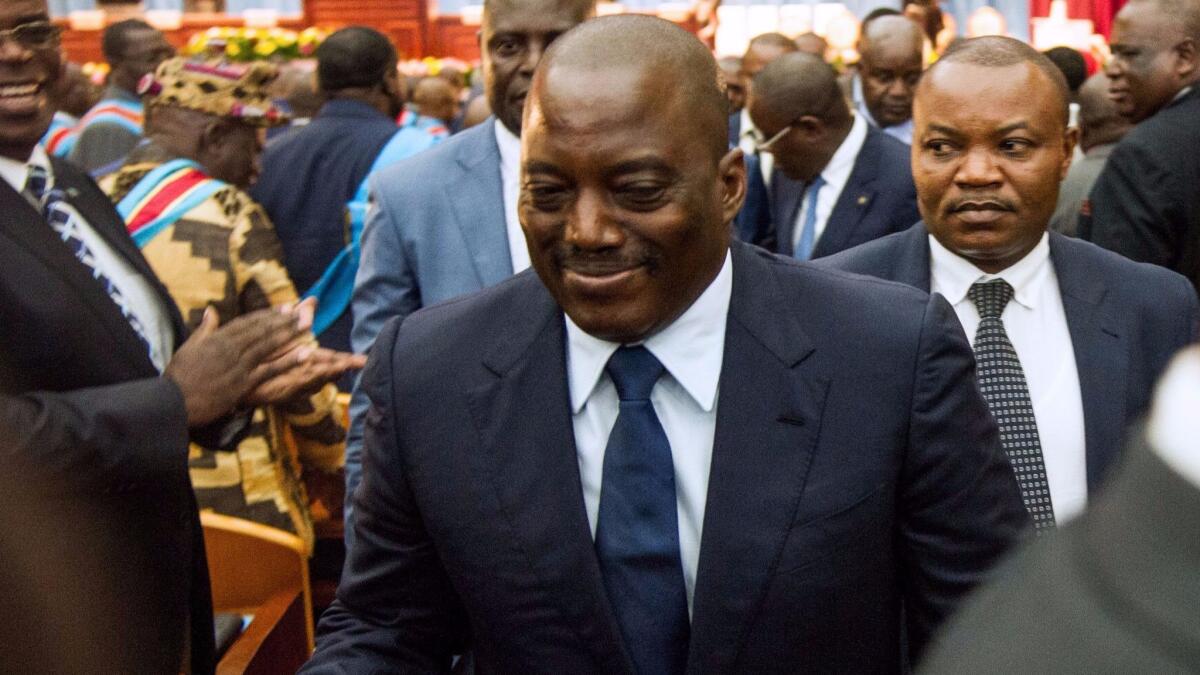

President Joseph Kabila’s last constitutionally permitted term at the helm of the Democratic Republic of Congo is about to end without the election of a successor, putting an already bloodied nation at risk of another spiral of violence with the potential to destabilize Africa’s Great Lakes region.

Opposition supporters are threatening to take to the streets to demand Kabila’s departure when his mandate expires Monday.

Mediators from the Roman Catholic Church have been making a last-ditch attempt to avert a showdown with the country’s security forces. But the president, who won two elections and is barred from seeking a third term, has shown little inclination to step aside.

In October, Kabila’s governing coalition struck a deal with part of the opposition to push back a presidential poll due last month to at least April 2018, citing budgetary constraints and problems registering millions of voters. A controversial decision by the nation’s constitutional court allows him to remain in office until the vote takes place.

In a bid to mollify critics, Kabila has appointed a minor opposition figure, Samy Badibanga, as prime minister and tasked him with forming a caretaker government. But leaders of the main opposition coalition — the Rassemblement, or Rally — reject the power-sharing arrangement.

They worry that the failure to adhere to the electoral schedule would allow Kabila time to amend the constitution so he can run again — a strategy used by a number of regional leaders, including those in neighboring Republic of Congo, Uganda and Rwanda.

Kabila insists that the constitution will be respected but has also floated the idea that it could be changed, if the Congolese people wish it.

In an address to Parliament last month, he sounded a defiant note, telling cheering lawmakers that he won’t allow the state to “be taken hostage by a fringe of the political class.”

Congo has not had a peaceful transfer of power since independence from Belgium in 1960.

Diplomats and human rights advocates warn that Kabila’s refusal to say if and when he will step down increases the likelihood of major bloodshed in the coming days and weeks.

At least 53 people were shot, beaten, burned, stabbed or hacked to death with machetes when anti-government protesters clashed with the security forces in the capital, Kinshasa, over several days in September. Most of the victims died at the hands of government agents, according to a U.N. investigation, but protesters also killed four police officers.

“The Democratic Republic of Congo has entered a period of extreme risk to its stability,” the U.N. envoy to the country, Maman Sidikou, told the Security Council in October.

Congo’s tanking economy, rampant poverty and corruption, repressive government and history of armed conflict have created an explosive environment that some have likened to the period before the country’s notorious dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko, was overthrown in a revolt lead by Kabila’s father in 1997.

Millions of people died in the civil war that followed, most of them from hunger and disease. The fighting, which has been described as “Africa’s world war,” drew in armies from as many as nine countries, some of which are themselves going through turmoil and could be drawn into another battle in Congo.

Many of the nation’s armed groups that took part in previous conflicts remain active today and some have intimated that they will no longer consider the army and police legitimate forces after Monday.

The scope of the threats, Sidikou warned, “dramatically outstrip” the capabilities of an 18,000-strong U.N. peacekeeping force deployed to Congo.

“Actors on all sides appear more and more willing to resort to violence to achieve their ends.”

What do Congo’s people want?

Kabila’s supporters credit him with restoring a measure of stability to Congo after his father was assassinated in 2001. A 2002 peace deal paved the way for a new constitution, the first multiparty elections in 46 years and a period of economic growth as mining companies poured billions of dollars into the vast, mineral-rich nation that is home to about 80 million people.

But support for Kabila has plummeted since he won a second disputed election in 2011. A nationwide survey carried out this year by the Congo Research Group at New York University, in collaboration with a Congolese polling institute, found that more than 81% of respondents oppose changing the constitution to allow him to seek a third term and fewer than 8% would vote for him.

The question is how far people are willing to go to force Kabila out of office. Many Congolese are just as skeptical of major opposition leaders such as Etienne Tshisekedi, who twice served as prime minister under Mobutu and is said to be angling to get his son into the job.

“So you have a disconnect between a very impoverished people and a political-social class that basically negotiates, cuts deals amongst themselves,” said Hans Hoebeke, an analyst with the International Crisis Group, a Brussels-based think tank.

What happens next?

A government crackdown appears to have had a chilling effect on Kabila’s opponents.

Since September, rallies have been banned; scores of activists have been arrested and media outlets associated with the opposition have been shut down.

Telecommunications firms have been instructed to block access to social media networks beginning at midnight Sunday. Even the national soccer league has been suspended since fans started chanting in the stands that Kabila’s time was up.

Still, opposition parties are under pressure to show they can deliver on their threats to mount protests. Frustration over the government’s repressive policies, rising prices and the high jobless rate among Congolese youths could bring people out onto the streets, analysts say.

All sides are bracing for the possibility of violence.

Residents of the capital have been stockpiling food; senior officials and members of the diplomatic corps have been moving family members to safety, and the U.N. peacekeeping force has been sending troops to potential flashpoints.

What is the international community doing about all this?

The United States and European Union this month announced sanctions — including asset freezes and travel bans — against nine senior Congolese officials accused of playing a role in the violent repression of recent years. The hope is that this will serve as a deterrent against further abuses and persuade the government to reach a deal with opponents that will see elections take place as soon as possible.

Congo’s neighbors, too, have been pressing all sides to come to terms, although their concern is less about upholding democratic institutions than the potential regional fallout if violence spins out of control in Congo.

Even if there are no major demonstrations in the coming days, the stage is set for a deepening crisis after Kabila’s term officially ends.

“It’s not just about managing the 19th and 20th of December,” Hoebeke said. “What comes after is a regime that has a very, very limited power base, that has very limited resources as its disposition … This is a powder keg.”

Twitter: @alexzavis

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.