How Ebola spread to Mali: The lessons learned

When the father of Mali’s first confirmed Ebola victim, a 2-year-old girl, fell ill while working at a private clinic in neighboring Guinea, fellow townspeople suspected witchcraft.

The man’s father advised him to return to their native village of Sokodougou, more than 40 miles away in Mali, where he died of unidentified causes Oct. 3. The elder man would later die as well, one of several family members diagnosed with Ebola.

The family’s story illustrates some of the reasons why the Ebola virus spread so rapidly in parts of West Africa, infecting more than 13,200 people and killing 4,960, according to estimates reported to the World Health Organization.

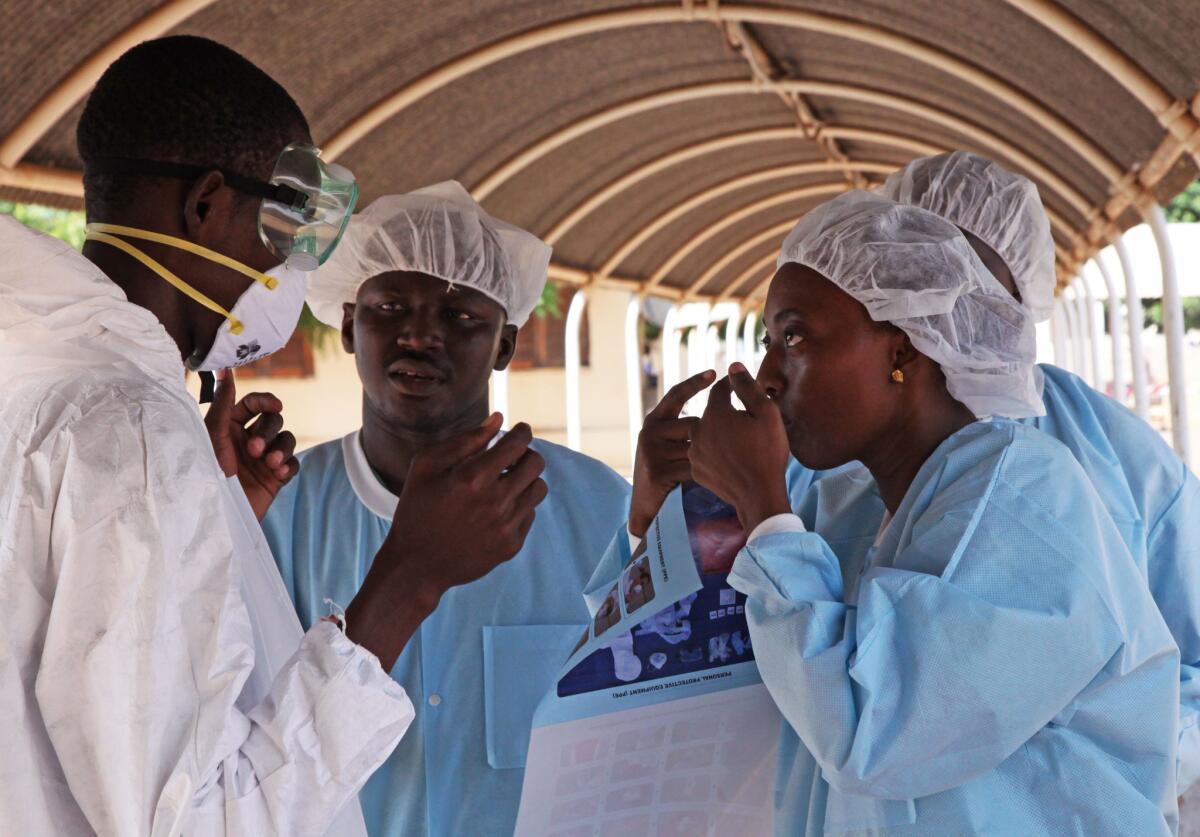

The virus struck in a region that had never seen Ebola cases before, where traditional beliefs about the source of disease are widespread, and where healthcare workers operating outside specialized treatment facilities often lack the equipment and training to protect themselves from infection.

It is also a region where people commonly return to their native villages to grow old or die.

“Such frequent travels by symptomatic Ebola patients, often via public transportation and over long distances, unquestionably create multiple opportunities for high-risk exposures – en route and also when the patient reaches his home and is greeted by family and friends,” the World Health Organization said in an assessment released Monday.

WHO officials helped the ministries of health in Mali and Guinea trace what happened to the family of the 2-year-old girl, who was diagnosed in the western city of Kayes on Oct. 23 and died the following day.

The girl lived with her family in the southeastern Guinea town of Beyla, where her father worked with the Red Cross and also provided care at a clinic owned by his father. There the girl’s father came into contact with a farmer who died of undiagnosed causes on Sept. 12, the WHO said.

The farmer’s two daughters, who had accompanied him to the clinic, died 11 days later, within hours of each other.

The 2-year-old’s father fell ill in the third week of September. Beyla residents believed he was the victim of a bad-luck curse following an argument with a traditional chief.

The man’s father was later diagnosed with Ebola and died at a treatment unit in Gueckedou, Guinea, the WHO said. Two of his other sons also tested positive for the virus, and one of them died.

The 2-year-old left Guinea on Oct. 19 with her 5-year-old sister and two relatives from her mother’s side of the family. The child was already showing signs of Ebola when they embarked on the 745-mile journey through Mali to Kayes, taking at least one bus and three taxis, and stopping to visit relatives in the capital, Bamako.

Once in Kayes, the family consulted two traditional healers. One of them took them to a retired nurse, who suspected Ebola and referred the child to the hospital, where she died.

Authorities in Mali identified 108 people who came in contact with the child when she was infectious, including 33 healthcare workers. So far none of them have developed symptoms.

A laboratory established with the help of the U.S. National Institutes of Health to test for tuberculosis and HIV was repurposed to safely test for Ebola, the WHO said. The Malian government also accelerated the completion of an isolation facility at the Center for Vaccine Development in Bamako.

“With persistent and thorough contact tracing, isolation and monitoring in place, confidence is growing that no further spread within Mali followed exposure to the index case, who had hemorrhagic symptoms but no diarrhea or vomiting during her travels,” the WHO said.

For more international news, follow @alexzavis on Twitter

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.