A remote Indian island, its fiercely isolationist inhabitants, and the death of an American missionary

In 1879, British colonialists forcibly brought an elderly tribal couple and some children from their remote Indian island to the nearest city. The sudden collision with modernity caused the islanders to fall ill, and the husband and wife died.

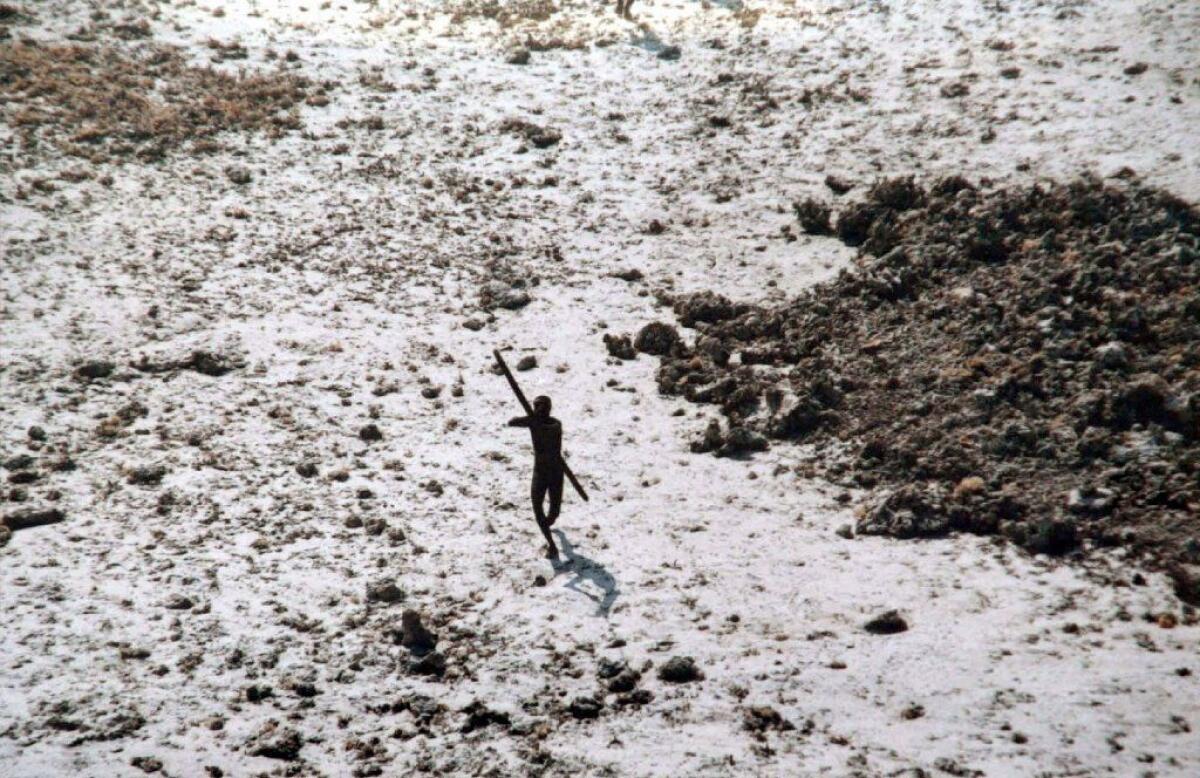

More than a century later, when an Indian Coast Guard helicopter flew over North Sentinel Island to survey damage following the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, a tribesman standing naked on the beach raised a bow and fired an arrow at the chopper.

The message was clear: The Sentinelese tribe, perhaps the most isolated people in the world, would like to stay that way.

So it was grimly predictable that a young American missionary who trespassed onto North Sentinel last week was killed by the tribe, according to Indian police, and his body buried on the beach. He was believed to have been shot with arrows.

The death of the American, identified as 26-year-old John Allen Chau of Washington state, has focused attention on the Sentinelese and on India’s efforts — not always successful — to limit contact with the descendants of hunter-gatherer tribes that have inhabited the Andaman and Nicobar archipelago for tens of thousands of years.

“This American tourist, he just went face-to-face with them, which no one is doing,” said P.C. Joshi, an anthropology professor at Delhi University who has studied the Sentinelese. “That was a very serious mistake on his part.”

The Associated Press reported Thursday that authorities in Port Blair, the capital of the 300-island chain in the Bay of Bengal, were studying options for recovering Chau’s body by consulting anthropologists, tribal welfare experts and scholars.

The protected island of North Sentinel is off-limits to outsiders, and any contact with the indigenous people is banned. Indian police officials said they had arrested seven people they said helped Chau reach the island, including a group of fishermen he reportedly paid $325 to bring him near the shore on Nov. 16.

There is no chance of legal action against the Sentinelese, one of the last “uncontacted” tribes on Earth.

In 2006, the islanders killed two fishermen when their boat accidentally drifted onto North Sentinel. When the coast guard attempted to retrieve the bodies, it was met with a volley of arrows.

Authorities now observe an “eyes-on, hands-off” policy, watching North Sentinel’s shoreline from a distance so as not to disturb the tribe. An outsider’s mere presence could introduce pathogens into a community that has never been exposed to many basic illnesses, said Jonathan Mazower, spokesman for the London-based advocacy group Survival International.

He called Chau’s decision to “declare Jesus” to the tribespeople — as expressed in a letter he wrote to his parents and left with the fishermen — “incredibly foolhardy.”

“They’re in real danger of being wiped out by deadly diseases such as flu and measles, which they will never have encountered before and to which they have no immunity,” Mazower said.

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands — shaded by palms and ringed by coral reefs — are India’s most distant territory, lying closer to Myanmar and Thailand than to mainland India. They were used by British colonial rulers as a penal colony.

The presence of ancient tribes has only added to the islands’ exoticism.

The Sentinelese, named for the Manhattan-sized islet they occupy, are among four tribes in the islands that are believed to be direct descendants of the first human populations of Africa. While others have slowly expanded their contact with outsiders, the Sentinelese live much the way their Stone Age ancestors did — except they now fashion tools and weapons from metal salvaged from shipwrecks, according to Survival International.

No accurate count of their population has ever been done, but experts say they number fewer than 100. The last Indian census on the island in 2011 — a visual survey conducted from boats offshore — counted only 12 men and three women.

They live in a jungle some distance from the beach, harvesting forest fruits and killing crabs and pigs for food, experts say. But their language, distinct even from other tribal groups in the islands, signifies how little contact they have had with other humans.

In 2001, census takers tried to communicate using words and gestures common to the Jarawa — another Andaman tribe from which they are believed to have descended — but found the Sentinelese couldn’t understand them.

The few anthropologists and tribal affairs officials who have visited the island have often done so at night, leaving gifts of coconuts, bananas and bits of iron on the beach before leaving. But several years ago, in response to a campaign by Survival International and other groups to leave the Sentinelese alone, India stopped sanctioning the visits.

In 2012, the government enacted a law that barred tourism and strictly limited commercial activity in tribal areas to prevent contact with natives. The law came into effect after a video emerged showing a scantily clad Jarawa woman being made to dance for tourists, fueling an outcry against “human safaris.”

Yet the islands’ mystique for adventurers has only increased.

Chau, a prolific traveler who has documented his expeditions on Instagram, had made four previous trips to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands since 2015, officials said. Arriving in India on a tourist visa in mid-October, he paid the fishermen to take him near North Sentinel on Nov. 14, then paddled ashore in a kayak, officials said.

He took fish and a football as gifts but retreated after he was attacked with arrows, one of which stuck in a Bible he was carrying, he wrote in the letter left with the fishermen, according to local news reports.

He returned to the island Nov. 16. The next morning, the fishermen watched from their boat as Sentinelese dragged Chau’s body along the beach and buried him, according to Andaman Island police officials quoted in local media.

In a post on his Instagram account, Chau’s family members said he “had nothing but love for the Sentinelese people” and said they “forgive those reportedly responsible for his death.”

Many Indians did not view Chau’s expedition as charitably. Some noted that it coincided with Thanksgiving, which whitewashes the disease and genocidal violence white settlers inflicted on Native Americans.

Brahma Chellaney, an author and commentator, called Chau a “nutty American” who had committed a “real sin.”

Others hoped the incident would prompt stronger protections for the Sentinelese.

Joshi, the anthropologist, said other Andaman tribes’ encounters with modernity had not left them better off. Indian settlers have overtaken Jarawa forests, exposing the natives to alcohol and tobacco and subjecting some women to sexual abuse.

“We so-called civilized human beings tend to give them the bad things first,” he said. “I am not for caging these people. There may be a time the Sentinelese will come closer to us. Right now their choice seems to be, ‘Don’t disturb us,’ and we must respect that.”

Special correspondent Masih reported from New Delhi and Times staff writer Bengali from Singapore.

Shashank Bengali is Southeast Asia correspondent for The Times. Follow him on Twitter at @SBengali

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.