Calif. bans spam, sets fines

SACRAMENTO — Gov. Gray Davis signed into law Tuesday a groundbreaking bill aimed at banning often offensive “spam” advertisements from the online mailboxes of millions of California computer users.

The measure, by state Sen. Kevin Murray (D-Culver City), would make it illegal for spam marketers and their advertisers to e-mail Californians, unless the recipient had specifically requested it or had had a prior business relationship with the advertiser, such as a bookseller.

Violators would be subject to a fine of $1,000 for each unsolicited message and up to $1 million for blitz campaigns in which hundreds of thousands or even millions of unsolicited sales pitches are sent out daily.

As Davis signed the bill, SB 186, he announced that he had also signed or soon would approve other measures in a package aimed at protecting the privacy of Californians and guarding them from identity theft.

Many states, including California, have enacted laws aimed at cracking down on unsolicited e-mail, whose topics can include products such as sexual enhancers, “anti-aging” creams, weight-loss pills and heavily discounted home loans. But Murray said his bill, effective Jan. 1, would be the first to hold an advertiser liable along with the spam merchant.

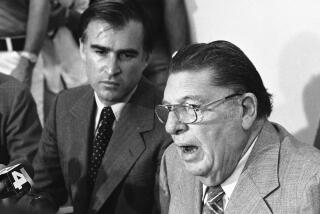

“We think it is going to be the toughest bill in the nation,” the senator said Tuesday. “The beauty of this is you go after the advertisers. They are fineable and attachable.”

Murray noted that spam has increased astronomically in the last couple of years and said it costs frustrated businesses and consumers billions of dollars in wasted time as well as the costs of trying to prevent it.

The new law will allow state Atty. Gen. Bill Lockyer, Internet service providers and individual citizens to sue spam marketers and their advertisers in civil court. Backers of the bill said that feature alone would discourage spam.

As the bill traveled through the Legislature, lawmakers agreed that it would be relatively easy for California to win judgments against spam merchants and their advertisers in state courts. But some considered actually recovering damages from those outside the state and overseas problematic.

Currently, the state routinely sues out-of-state and foreign companies that do business in California for a variety of offenses, such as fraud and false advertising.

Lockyer spokesman Tom Dresslar said, for example, that a judgment could be made in favor of the state against a spam merchant in Beijing, but that it “may be more difficult, depending on distance and the circumstances, to collect. But that doesn’t mean we don’t go after the guy in Beijing.”

Dresslar said Lockyer, who is currently prosecuting a spam merchant under another law, intends to aggressively enforce the anti-spamming law.

Murray disagreed that fines would be difficult to collect against spam merchants located beyond the California state line. He said that since virtually all online transactions involve the use of four internationally recognized credit card companies based in the U.S., it would be relatively easy to locate the offender’s bank accounts and attach them for the amount of the fine owed.

Or, Murray said, the plaintiffs could sue a credit card company and attempt to attach the spam merchant’s or advertiser’s revenue that traveled through the company’s channels.

“As long as we know where your money is, we can attach it,” he said.

David Kramer, a partner in the Wilson Sonsini law firm in Palo Alto, has been dealing with efforts to control e-mail spam for seven years.

He said the only other state to pass a law banning spam is Delaware.

“It’s not working there,” said Kramer, “because banning spam is only half the battle. You actually have to create an effective enforcement mechanism to make sure the prohibition is enforced.”

In Delaware, the principal enforcer is the attorney general, who is busy with more serious crimes.

The new law in California “not only gives victims the ability to seek redress for themselves,” Kramer said, “but it also creates a means of serving the public interest, because those suits create deterrent and the threat of those suits creates deterrent.”

He said he hopes that the California law will not be abused as he believes the right to take private action has been in Utah, where the law allows a spam recipient to sue for $10 for every e-mail. There, two law firms have filed 1,500 individual lawsuits seeking $6,500 settlements with e-mail senders, said Kramer.

The California bill was backed by a variety of consumer advocates, who had made protection of residents’ privacy a leading issue of the recently concluded legislative session.

Murray said the new law will require recipients to give their consent before receiving a sales pitch via e-mail, unless the individual and the entity had previously done business. In that case, the recipient could demand that no more unsolicited messages be sent.

In a statement, Davis said the California law will signal to the nation that the “time has come for unscrupulous spammers to stop feeding our e-mail boxes a daily diet of unwanted e-mail.”

Several bills have been proposed this year in Congress that would restrict the use of commercial e-mail. Sen. Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) has called for a federal anti-spam registry, similar to the do-not-call registries for telemarketers. That would enable consumers to prevent unsolicited commercial e-mail. And Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) has co-sponsored a bill that would impose stiff civil penalties on spammers who failed to include valid links allowing recipients to unsubscribe to unwanted e-mails.

Davis, however, warned against other federal legislation that threatens to overturn new privacy measures in California and nullify several existing identity-theft laws.

One potential target is the heavily contested California law that requires banks and other financial institutions to first obtain a consumer’s consent before his or her private financial history can be sold or traded to third parties for marketing purposes. The law also clamps restrictions on which companies in a business family can and cannot receive such information without the customer’s advance approval.

Legislation is moving in both houses of Congress that would throw out the law, written by state Sen. Jackie Speier (D-Hillsborough), on grounds that state laws cannot be stricter than federal laws.

Instead of wiping out California laws, Davis said in a letter to congressional leaders, “Congress should consider them as a model for the rest of the nation.”

He said that, if nothing else, the federal legislation should exempt California.

In the Legislature, the Murray proposal drew surprisingly little opposition.

But the California Assn. of Realtors expressed fear that the bill would limit its ability to send electronic notices of trade shows and seminars to its 130,000 members.

Stan Wieg, an association lobbyist, said it would be hard for local chapters, often run by volunteers, to keep up on who does and doesn’t want such information.

“You can see how you can be tripped up by that sort of record-keeping obligation,” he said.

The direct-marketing industry, which opposed other privacy bills, did not fight the Murray proposal. But industry observers warned that the new law would not touch the most notorious spam merchants, which are based outside the United States.

“It fails to address the core issue about spam. It totally fails to be able to reach the offshore criminals who are sending Viagra ads,” said Ray Schultz, editorial director of Direct, a magazine that covers the direct-marketing industry. He said the industry would prefer to see a uniform federal law that supersedes state statutes.

Another bill signed Tuesday by Davis was SB 27, which will require firms that have divulged a customer’s personal financial information to others to inform the customer, upon request, which third parties received the information and what it contained.

Times staff writer Nancy Vogel contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.