In Liverpool there’s just one game in town — soccer — but two teams just a mile apart

Ian O’Brien stood outside Anfield, the refurbished home of the Liverpool Football Club, rubbing his ruddy hands together in an unsuccessful effort to ward off an early morning chill when a stranger approached.

“Where’s Goodison Park?” the man asked.

“Don’t swear in here, mate!” O’Brien snapped before turning away.

Goodison Park, you see, is the stadium used by Everton, Liverpool’s chief rival. If Anfield is a cathedral — and O’Brien, a tour guide there, believes it is — then any mention of Everton on its grounds is like invoking Satan on Easter Sunday. The same holds true, in reverse, at Goodison Park, which sits on the north end of Walton Lane, less than a mile away.

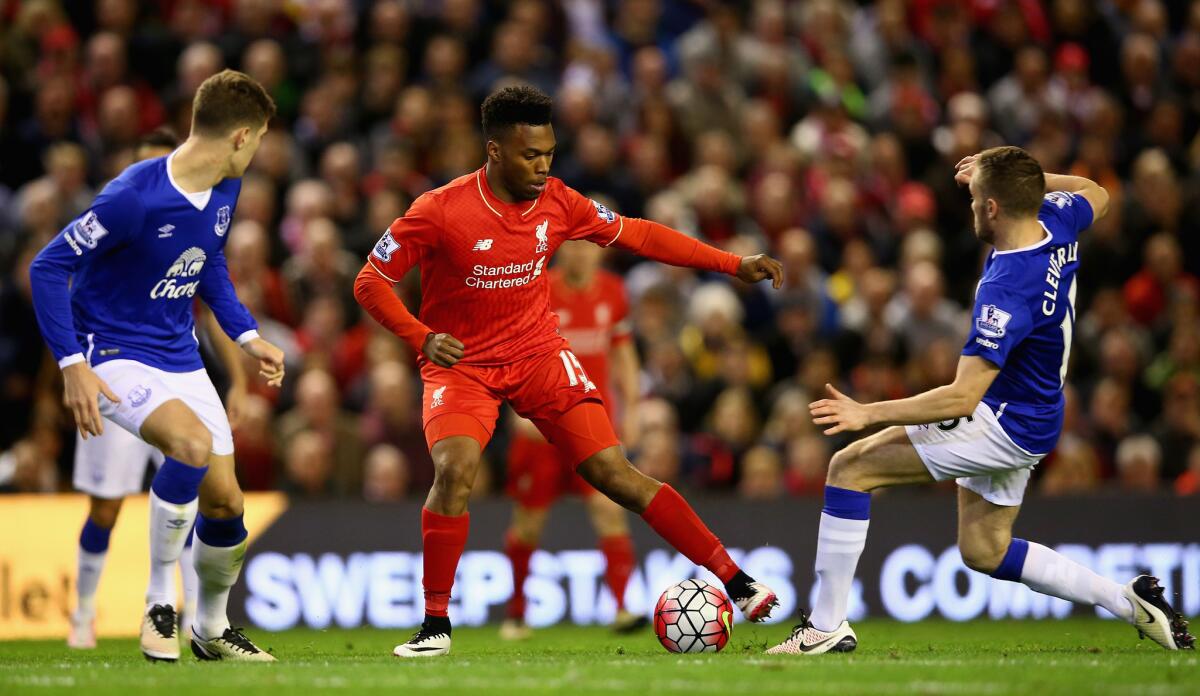

Few sports rivalries as are passionate as the one between the Blues of Everton and the Reds of Liverpool, which will be renewed Saturday when the teams meet at Anfield. And part of that fervor comes from the fact the two soccer clubs have occupied stadiums on opposite ends of Stanley Park, a spacious greenspace of gardens and lakes, for 125 years.

“It’s incredible,” said Tim Howard, the U.S. national team goalkeeper who played 11 years for Everton. “You do have some rivalries in U.S. sports like it — Bulls-Pistons late 1980s, something like that. But it’s not the same because it’s in the same city.”

The Bulls and Pistons, after all, were separated by 300 miles. The Yankees and Red Sox are 200 miles apart. Even UCLA and USC have 14 miles between them.

Liverpool and Everton are so close you can see one stadium from the other. On game days, they share the same parking lot. And that proximity not only fuels the passions of fans, it helps define this city of 478,000 perched on Britain’s west coast.

“Man it’s crazy,” said Howard. “It’s a close-knit community … and the city’s split. There’s no one family that’s blue and one family that’s red.

In English soccer a crosstown rivalry is called a “derby” — pronounced DAR-be — a term originally coined for an 18th century horse race, only to later become synonymous with any big sporting event. And few English sporting events are bigger than the Merseyside Derby, named for the river that runs through Liverpool.

Even Liverpool’s most famous sons, the Beatles, weren’t immune. Paul McCartney was said to be an Everton fan who attended games at Goodison as a boy, while John Lennon played a big role in getting former Liverpool forward Albert Stubbins included in the iconic cover for “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.” (He’s above and just to the left of Marlene Dietrich.)

Another former Liverpool player, Matt Busby, gets a shout out in the Beatles’ 1969 song “Dig It,” along with the BBC, B.B. King and Doris Day.

Everton and Liverpool have met 226 times since their first match in 1894 (a 3-0 Everton win), but for much of its existence, the rivarly was referred to as “the friendly derby.” While supporters of other English soccer teams generally inherit a lifelong allegiance to one — and only one — club from their fathers and grandfathers, in the working-class neighborhoods surrounding Stanley Park people often cheered for both teams.

Phil Thompson, who grew up six miles outside Liverpool as a Reds fan before going on to play nearly 500 games for the team, remembers those days fondly.

“People used to go to both games. They’d go watch Everton on a Saturday; the following Saturday they’d go watch Liverpool,” said Thompson, who coached at Liverpool. “So many mixes of families. Brothers and sisters and dads could be Liverpudlian and the sons could be Evertonians because their uncle might have taken them to watch Everton.”

That camaraderie has waned over the last 25 years, turning what had been a family affair into a family feud, and Thompson blames Liverpool’s success for the change. Since the inception of the Premier League in 1992, Liverpool has finished in the top four in the standings 13 times, captured the Football Assn. Challenge Cup twice and won a Champions League title.

Everton, meanwhile, has finished as high as fourth in the league table just once, won one “FA Cup,” as the competition is known here, and has never advanced beyond the round of 16 in a major European competition.

And that’s imbued Liverpool supporters with a certain arrogance and Everton fans with jealousy, splitting households as well as entire neighborhoods.

“It’s not friendly anymore,” Thompson says. “There’s a new generation and I think maybe it’s fueled by social media. It’s bitter.”

That’s since spread to the field, with referees issuing more red cards for violent play in the Merseyside Derby than in any other crosstown rivalry in the English Premier League era.

So while that edgy, even violent, form of sports boosterism known as hooliganism has largely faded from the English Premier League in recent years, tensions often run high at the Merseyside Derby, which is played twice a year, once in Goodison Park and once in Anfield.

Two years ago local police, fearing violence, took legal action to try to move the kickoff at Goodison Park to earlier in the day — to give people less time to drink before the game. They backed off after Everton officials agreed to segregate the seating areas, keeping rival fans — including those who lived in the same house — from sitting next to one another.

And the first meeting this season, at Everton in December, was marred by several rough tackles on the field and a lit flare thrown from the stands at Liverpool’s Sadio Mane, who scored the lone goal. (He wasn’t hit.)

Soon even the stadiums will be kept apart. Everton announced plans last week to move out of the iconic-but-crumbling Goodison Park to a new home on the Liverpool docks, two miles to the west.

John Henry, Liverpool’s American owner and also owner of the Boston Red Sox, renovated and modernized Anfield last summer, swelling attendance in the main stand by more than 8,000 seats and building an exclusive director’s box, updates that could add millions to the team’s bottom line each season.

Those are options that aren’t available to Everton since its current 39,571-seat stadium, squeezed tight into a residential neighborhood, cannot grow beyond its current footprint in what’s known as the “Blue Mile.” The team, owned by British Iranian billionaire Farhad Moshiri, is scheduled to abandon Goodison, the oldest purpose-built soccer stadium in the world, for the new 50,000-seat home by 2020.

But when Everton moves and fans will no longer be able to see one stadium from the other, sportswriter Chris Beesley, who covers the Blues for the Liverpool Echo, doesn’t see the rivalry changing much.

“The derby,” he said, “is going to be ferocious wherever it is played.”

ALSO

Visual timeline of key events related to Britain’s decision to leave the European Union

Russia’s meddling in other nations’ elections is nothing new. Just ask the Europeans

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.