70 years later, Spanish historian repeats the act that led to his arrest under Franco

At the age of 92, the historian Nicolas Sanchez-Albornoz is an unlikely graffiti artist. But on Tuesday, 70 years after being sent to a prison labor camp in a wave of repression by Spain’s Franco dictatorship for painting the words “Long Live Free University!” he returned to the scene of the crime for a symbolic reconstruction of the slogan.

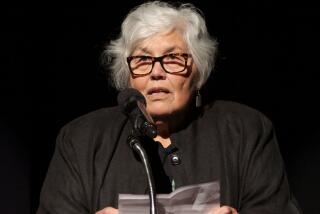

“I am moved,” a tearful Sanchez-Albornoz said after receiving tributes from students at Madrid’s Complutense University, where he had been arrested as an undergraduate in 1948 along with 13 other members of the underground University Students’ Federation. He was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment in a work camp on the site of Gen. Francisco Franco’s colossal mausoleum, now known as the Valley of the Fallen.

“When I was at university, we couldn’t imagine seeing an event like this,” Sanchez-Albornoz said before applying the first slosh of black paint to the symbolic reconstruction on the wall of the political science and sociology building.

The event was held on a notorious date in Spain — Nov. 20 — when groups of Franco sympathizers mark the anniversary of the deaths of the dictator, in 1975, and that of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, founder of the fascist Falange party, who was executed by Republican forces in 1936, the first year of the civil war that led to a four-decade dictatorship. According to the Francisco Franco Foundation, 16 churches around Spain were holding special Mass services for the dictator on Tuesday. At the Valley of the Fallen basilica 30 miles northwest of Madrid, several hundred fascist supporters joined in prayer, some offering stiff-arm salutes over the military ruler’s tomb.

Spain’s socialist government has said it will soon end the “anomaly” of honoring the dictator’s resting place in a public building. It plans to exhume Franco’s remains and allow his family to bury them privately. However, Franco’s grandchildren want his body re-interred in Madrid’s cathedral, leading to a delay in the government’s plans as it seeks a legal remedy to prevent the country’s former dictator swapping one monumental tomb for another — in the center of the capital.

Sanchez-Albornoz turned out to be among the more fortunate of those who ran afoul of Franco. He escaped the concentration camp after a few months and, together with his fellow university activist, Manuel Lamana, slipped through a security cordon and made it to the nearby monastery town of El Escorial. There, two young American women, the author Barbara Probst Solomon and Barbara Mailer, sister of the author Norman Mailer, were waiting in a small Renault they had driven from Paris. Counterfeit ID papers for the two men allowed the group to pass roadblocks and guards on the border with France.

Freedom for the two men also meant exile, however. They both moved to Buenos Aires, where Lamana died in 1996, while Sanchez-Albornoz was exiled again, this time to the United States, when Argentina itself became a military dictatorship. He became a professor of history at NYU, eventually moving back to Spain after Franco’s death to become director of the Cervantes Institute.

Lamana’s daughter, Maruja Lamana, joined Sanchez-Albornoz at the ceremony, expressing anger at what she sees as Spanish amnesia over the dictatorship.

“You cannot build a dignified society while denying the past,” she said. “Schools do not offer information on the Franco era or the civil war, and half of society does not distinguish one side from the other when what happened was a coup against democratic Republican Spain.”

Sanchez-Albornoz said that his former prison camp was built as a “monument to the glory of Franco’s Nationalist crusade” by prisoners whom the state rented to construction companies. “They charged the firms 10.5 pesetas per prisoner a day, and the budget to feed us was five pesetas. There was no cost; the regime made money out of us. The whole system was corrupt and the civil servants stole half of the food sacks to sell on the black market.”

The historian believes that the monument was so poorly built that it will eventually crumble. Except for the 150-meter stone cross that stands over the basilica, he said dynamite would speed things along. “Nature should be allowed to take its course, but with a little helping hand.”

Badcock is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.