In Lviv, Ukraine, the nation’s east-west divide is on display

If this western Ukrainian city of Baroque fountains and cobblestone squares seems like a different country from the eastern rust belt besieged by pro-Russia separatists, that may be because, for most of its history, it was.

Wooden signs in Lviv’s Rynok Square hawk homemade pirogies and stuffed cabbage rolls, tastes imparted by the Poles who ruled here for 400 years. Chestnut-shaded promenades and pastel-painted villas evoke Budapest, Prague and Vienna, sister cities of the Austro-Hungarian era when Lviv was called Lemberg.

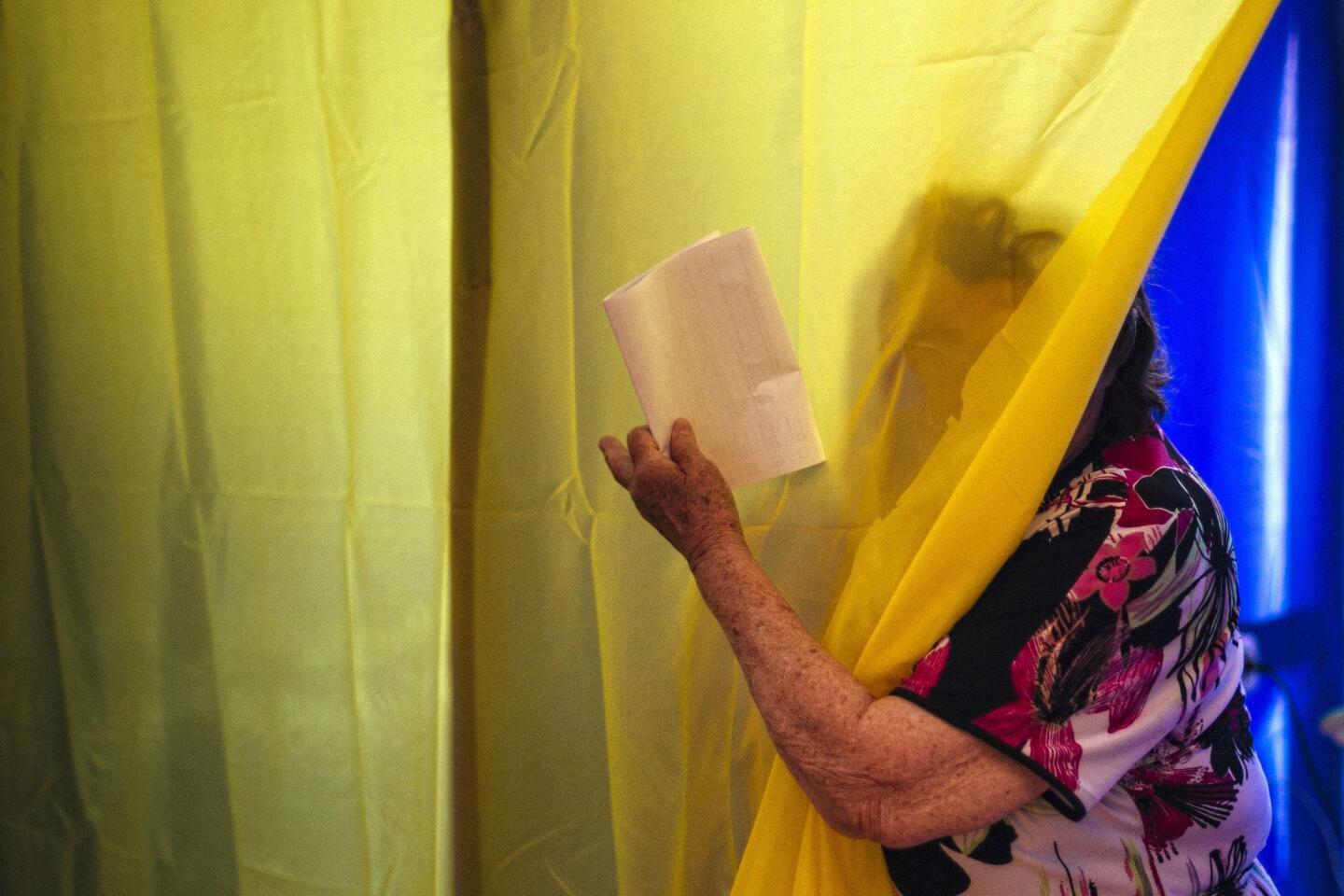

The question of what it means to be Ukrainian is central to the dispute that has roiled the country for months, leading to an election Sunday to choose a new president. Petro Poroshenko, who has a commanding lead, is expected to win handily, either by gaining an absolute majority in the first round or in a June runoff.

Despite the region’s history, which includes virulent anti-Semitism and collaboration with Nazi occupiers, Lviv residents say they embody a Ukrainian character that includes a Western orientation and respect for human rights. Russian officials and leaders of the separatist movement characterize western Ukraine as a hotbed of unrepentant fascism. And many Russians question whether there is even a separate Ukrainian nationality or language.

These sharply diverging views threaten to cleave Ukraine into a Russian-speaking eastern region that is dominated by Russia and western areas that return to their Central European origins.

“Most Russians perceive Ukrainians not as the people of a separate nation but as Russians who speak a different dialect,” said Iryna Matsevko, deputy director of the Center for Urban History of East Central Europe. She traces the emergence of a clearly defined Ukrainian nation only to the Soviet era but contends that the cultural and linguistic distinctions date back centuries.

Scholars here say that really isn’t much different, in some ways, from the rest of Europe.

“Most European borders are not very old,” said Anna Susak, an earnest 27-year-old researching Ukraine’s sociological history for her doctoral dissertation. She points to the reunification of Germany, the breakup of Yugoslavia and the independence of Ukraine and other former Soviet republics in little more than two decades.

Though the Soviet era is about all that eastern and western Ukrainians share, those 70 years left a stamp on both sides of the country. As elsewhere in Ukraine, Lviv has its share of shabby, prefabricated apartment blocks on the city’s outskirts.

In the east, Soviet troops doggedly resisted the Nazis, and homes and industries were destroyed in the fighting. The war left eastern Ukraine, where pro-Russia separatists now occupy a dozen towns and cities, a ravaged canvas on which the Soviets built slapdash housing and factories that still blight the landscape.

Lviv’s capitulation spared it similar physical destruction.

Intellectuals who flock to this World Heritage city of 730,000 because of its abundance of universities say the good and the bad parts of its history make up the essence of what it means to be Ukrainian.

What defines Ukrainians now, says Yaroslav Hrytsak of Lviv’s Catholic University, is a set of shared values: pursuit of democracy, orientation toward the rest of Europe, respect for diversity and a commitment to eradicate the corruption that has impoverished Ukraine throughout its 23-year independence.

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s pursuit of a strong Russia intolerant of minorities, gays and dissent clashes with the ideals of pro-Europe Ukrainians whose success three months ago in overthrowing their elected president, Viktor Yanukovich, has been embraced as a mandate for reform and reintegration with Europe, Hrytsak said.

The professor said Ukraine still needs an honest assessment of its history. In the west, that includes anti-communist partisans who collaborated with the Nazis after the 1941 invasion, pogroms against the once-vibrant Jewish population, and the delivery of Jews to the Belzec extermination camp across the border in Poland. Hrytsak’s duties include overseeing a newly endowed Jewish studies program.

Poles and Jews comprised more than 80% of Lviv’s population before the war, but were virtually erased during the Holocaust and in the 1950s when Poles were relocated en masse to conform to the new Soviet-Polish borders.

The Orange Revolution a decade ago gave rise to Ukrainian nationalism, which has included the political resurrection of wartime partisan leader Stepan Bandera. As he left the presidency in 2010, Yanukovich’s predecessor, Viktor Yushchenko, bestowed the posthumous award of “Hero of Ukraine” on Bandera.

The honor was annulled a year later by court order, but the official embrace of the fascist collaborator has played into the Kremlin’s narrative that this country is ruled by neo-Nazis.

So has the recent opening of the Kryivka speak-easy in Lviv’s historic city center, where waiters in partisan olive drab bear wartime-era rifle replicas and insignia of the UPA, United Partisan Army. Patrons must whisper a Ukrainian nationalist phrase glorifying the fascist state to gain entrance.

“The UPA is part of our history. We just try to explain it in this way,” said Roman Kuchkuda, a 25-year-old public relations manager for the Fest business empire, who sees no harm in mocking the wartime era.

Other young professionals look askance at commercializing those aspects of the past, saying the heedless marketing of partisan paraphernalia shows the need for a thorough cleansing of the governing ranks and education leaders.

“We need to elect a new parliament as well as a president,” said Iryna Fogel, a project manager for a private development group who despairs of her city’s right-wing leaders. Some in the Lviv regional leadership were elected during periods of nationalist fervor while others were appointed by Kiev in concessions to the more extreme parties in order to build a governing coalition.

Lviv residents of all ages say they’ll vote despite a lack of enthusiasm for any of the candidates and the foregone conclusion that Poroshenko will win.

Hess Zinowy, a 73-year-old bachelor who augments his pension with chess matches that earn him about 40 cents per win, can’t identify a time in his life when he felt hopeful. He doesn’t see a presidential candidate that he likes, but still says he will vote.

Young voters are little more inspired, but look to the election as a first step on a long road.

“We are tired of these old names and faces,” says Dmytro Sherengovsky, a 27-year-old lawyer and human rights advocate. “But we are not idealistic. We know change will take time, at least a couple of generations.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.