Archive: Bristol, Conn.’s guerrilla hostage

The phone rings and Jo Rosano jumps to answer, thinking of the sound of her son’s voice: Hi, Mom, it’s me, Marc.

But it isn’t him. Rosano hangs up to resume scouring the Internet for news, brewing espresso, pacing, praying, crying and waiting -- as she has for the last five years.

“Day and night,” she says, “this is my life.”

Colombian rebels have held Marc Gonsalves and two other Americans hostage since February 2003, when their plane crashed during a drug surveillance mission for a U.S. military contractor.

For years, it seemed doubtful that Gonsalves, now 35, would be released from his jungle captivity. Then this month, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC, a Marxist rebel group, released two hostages -- out of an estimated 700 -- after Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez brokered a deal.

Now Rosano clings to rumors that more could soon be set free.

“The guerrillas are showing goodwill,” she says. The release of two hostages “was only the beginning.”

In her Connecticut home, Rosano, 59, keeps the television tuned to CNN. She smokes Capri cigarettes and clips news articles about the hostages from local newspapers that pile up on her glass coffee table among doily place mats, a bottle of pink nail polish and a tube of mascara. She dabs foundation beneath her eyes to cover dark circles and jots Bible verses on stationery to give her strength. And she watches a video over and over on her laptop that shows her son alive.

She has memorized the way he stands in the footage, hunched against a backdrop of palm trees, hands behind his back, staring at the ground. His hair is thin, his eyes sad. The jungle around him is a chorus of hissing snakes, screeching birds and ominous howls. Gonsalves does not speak, and the cries of the wild give Rosano chills. She kisses her fingers and presses them against the computer screen to touch his face.

Based on news reports, conversations with a former hostage who escaped, and messages sent to relatives from those still in captivity, Rosano knows this much: Her son sleeps in a hammock or makeshift bed, covered by a mosquito net and a tarpaulin, chained at the neck to other prisoners, amid a haze of horseflies, ants, wasps and spiders. Gonsalves survives on rice, beans and yuca, and suffers from hepatitis. Rigged explosives and camouflaged rebels carrying AK-47s surround the hostages, who are often forced to march for days through brush and wade through raging rivers.

Since her son’s capture, Rosano has traveled to Colombia three times seeking his release, and she has visited Washington a dozen times to beg lawmakers to help. In September, she met with Colombia’s president, Alvaro Uribe, at the United Nations in New York.

She seizes every crumb of information about her son’s life, holding them as hints that he is alive and coming home soon -- even if it is not true, even if her heart breaks from dashed hope time and again.

One afternoon last week, the phone inside Rosano’s home rings again. All morning, Colombian journalists have been calling to ask if she heard the latest rumor that one more hostage may be released. Rosano recognizes the phone number on her caller ID: It is a filmmaker and friend, Victoria Bruce, who co-directed and co-produced a documentary, “Held Hostage in Colombia,” which featured Gonsalves.

“Hey,” Rosano answers. Bruce tells her she has heard the rumors and hopes they may be true. The possibility of her son coming home overwhelms Rosano.

“Oh my God, Vicky,” she says, falling to the couch. She cradles a pillow and rocks back and forth. “Oh my God.”

She hangs up as her husband, Mike Rosano, 66, walks into the living room and sees her sobbing and trembling.

“Is he coming home?” he asks blankly. He has been through this before.

“There is an American being released,” she tells him.

“But we don’t know if it’s Marc,” he replies.

“I think it’s Marc,” she says. “I hope it’s Marc.”

She did not want her son to take the job.

In 2002, Gonsalves, a former Air Force intelligence officer, told his mother he had been hired for a six-figure salary by a subsidiary of Northrop Grumman Corp. The large military contractor was paid by the Pentagon to find cocaine labs in Colombia’s jungles at a time when the U.S. government had been aggressively waging a war on drugs.

Gonsalves would leave his wife, daughter and two stepdaughters at home in Florida for weeks at a time traveling to Colombia to survey fields of coca. He planned to keep up the routine for three years, Rosano recalled, because he wanted to save money to buy a house. The job would involve flying in a small plane over mountainous terrain and tropical forests, and the thought of that frightened Rosano.

On Feb. 13, 2003, four months after he started work, Gonsalves boarded a single-engine Cessna loaded with photography equipment. Four others accompanied him, including three Americans: Thomas Howes, Keith Stansell and Thomas Janis.

As they were returning to their base, the engine cut off and the plane plummeted. The crew issued a mayday call over the radio before smashing into a grassy area off the mountains controlled by the FARC. Guerrillas surrounded the crumpled plane and shot and killed Janis and a Colombian intelligence operative. The rebels marched the three survivors into the jungle.

“For the next two months, I lived in a dark room. . . . I got no information,” Rosano said.

Six months later, she received a video taken by a Colombian journalist, Jorge Enrique Botero, who was granted interviews with the three hostages. He traveled 27 days into the jungle to meet with the men for six hours. The footage showed Gonsalves looking into a camera as he said: “I love you guys. And I’m just waiting to come home.” It devastated Rosano, but gave her hope: Her son was alive.

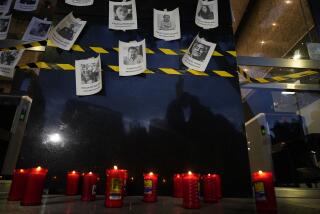

Rosano made her first trip to Colombia in 2004. Wearing a T-shirt with Gonsalves’ face silk-screened on it, she attended a demonstration outside of Colombia’s Congress building, along with hundreds of relatives of hostages held by the guerrillas.

Slowly, she was coming to understand the political unrest in Colombia and its connection to the United States. The group holding her son was made up of about 16,000 rebels, mostly peasants, who wanted more equitable distribution of wealth in Colombia.

They hoped to exchange hostages for what they call political prisoners held by the U.S. and Colombian governments. The European Union has sided with the U.S. in listing the FARC as a terrorist group, outlawing economic support for the guerrillas. The White House has refused to negotiate or pay ransom for the Americans’ release.

“What if it was your child?” Rosano said. “They have no idea what it’s like daily for us.”

In the last five years, Rosano has been the only member of her family to speak out publicly about Gonsalves, which has put her at odds with her ex-husband and another son. Her daughter-in-law is coping privately. After Rosano was interviewed in 2003 by her local paper, her son Michael stopped talking to her, accusing her of “wanting to be a star.”

Sen. Christopher J. Dodd (D-Conn.), who is working with the State Department to ensure families receive updated information about the hostages, said Rosano’s commitment to her son was unwavering. “I have always been inspired by her dedication to bringing her son and the rest of the hostages home safely,” he said.

Rosano says she does not want fame. Nor does she make money for speaking out. Instead, she says, she has struggled financially, spending thousands of dollars traveling to Colombia, Washington, New York and elsewhere to fight for her son’s release.

Not long after Gonsalves was kidnapped, Rosano began to question God. A Catholic priest she did not know called her at home after reading about the hostages. Rosano said she cried and asked him, “Why is God punishing me?” The priest replied, “God doesn’t work like that.”

Rosano began to read Job, and memorize parts of the Bible. “I started growing spiritually,” she said. “Yes, I fall. I fall many, many times.”

Last year, Jhon Frank Pinchao escaped from the jungle camp after nine years in captivity. He walked and swam for 17 days, dodging guerrillas, before police picked him up. He flew to Florida and met with Rosano and other families to give them information about their loved ones. Rosano called him her “messenger from God.”

From Pinchao she learned: Gonsalves had become spiritual, too, and he read the Bible and gave Mass with Holy Communion using bread. He had come down with hepatitis, which the guards treated with a diet low in salt and sugar. Sometimes when the hostages received boiled fish to eat, Gonsalves gave his to others. He picked up Spanish. He carried newspaper clippings about her fight for his freedom, telling other hostages: “This is my mom.”

The highlight of every day for the prisoners is listening to transistor radios at dawn when messages from relatives are broadcast over Colombia’s radio stations, Pinchao told her. Rosano knows this is the only way to communicate with her son, and she records messages telling him and the other hostages: “Don’t give up; I won’t give up. Keep your faith.”

She adds: “Remember, Marc, how much I love you, and I will continue this until you’re home, or until I stop breathing.”

Before all of this, Rosano and her husband often went bop and swing dancing. These days she cannot bring herself to have fun knowing her son’s leisure time consists of playing cards or lifting weights made of bags of dirt.

By September, Rosano had reason to believe her son’s release was coming soon. Venezuela’s Chavez announced plans to broker a deal between Colombian President Uribe and FARC leaders to discuss swapping 45 hostages for hundreds of suspected rebels held in Colombian prisons. Uribe has traditionally taken a hard line against rebel demands. To the surprise of many, he agreed to negotiate.

But on Nov. 21, discussions fell apart. Uribe accused Chavez of defying him by directly contacting the head of Colombia’s army to discuss the hostages. Rebel leaders had also failed to provide proof the captives were alive.

Rosano felt her strength withering away. It had been almost five years since her son’s capture, with no end in sight.

Then she received an uplift.

On Nov. 30, Colombian officials released video of Gonsalves, Howes, Stansell and former presidential candidate Ingrid Betancourt. The tapes, which appeared to have been recorded in October, had been seized during the arrest of three suspected FARC members and showed the hostages alive and apparently healthy. Gonsalves looked muscular in a T-shirt, windbreaker pants and rubber boots.

A breakthrough came Jan. 10. With Chavez mediating, the rebels released hostages Consuelo Gonzalez, a former congresswoman, and Clara Rojas, an aide to Betancourt. Rojas was kidnapped with the presidential candidate on the campaign trial in 2002 and gave birth in captivity to a child fathered by one of the guerrillas.

Rosano watched with elation as television showed the freed women reuniting with their families and Chavez in Venezuela. She got her passport in order. Any day now, Rosano thought, she would be there rejoicing, too.

‘I’m still shaking,” Rosano said. “Could this nightmare be coming to an end?”

The phone calls from journalists last week had sent her into a whirl of panic and excitement. This was it, she believed, her son was coming home.

“My faith in God has gotten me through all of this, and I believe that’s what has helped my son to survive these conditions in the jungle,” she said. “This is a miracle, and I always said 2008 is going to be the year of miracles. I feel like I’m dreaming this.”

She stayed by the phone keeping an eye on her caller ID, refusing to leave the house. She checked e-mail, watched television news, drank one espresso after another, flicking cigarette butts into an ashtray next to her open Bible on the coffee table, waiting for an official call or news release.

Night came. Snow fell. Still no word.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.