How WhatsApp is battling misinformation in India, where ‘fake news is part of our culture’

The video showed two helmeted men on a motorcycle circling a group of children playing cricket in the street. The motorcycle slowed, and the man in the backseat grabbed one boy and bundled him into his lap as the driver sped off.

Inside a college lecture hall, many of the 200 Indian students and law enforcement officers murmured in recognition. Asked how many had seen the video before, nearly half the students raised their hands.

The clip was part of an anti-kidnapping public service ad produced in next-door Pakistan. But with the ending edited out to make it appear like a real kidnapping, the footage went viral last year on WhatsApp, the Facebook-owned messaging platform with more than 200 million users in India.

What happened next marked a shocking low in the era of fake news.

Users circulated the video along with unsubstantiated claims that child traffickers were running loose in Indian cities, triggering mob attacks that left at least two dozen people dead. The killings reverberated from India to Silicon Valley and forced WhatsApp to confront — far too late, critics say — the deluge of rumors, hoaxes and misinformation swamping its biggest market.

As India heads into a bitter national election campaign involving parties that have frequently peddled half-truths and doctored videos, WhatsApp is mounting a feverish battle against fake news — tinkering with its app, bolstering local fact-checking organizations and airing national ads.

It has also launched an initiative to teach Indians how to become better social media users, spot hoaxes and keep from spreading them.

On an overcast morning in early January, that effort reached Assam, the northeastern state that saw one of the grisliest WhatsApp-related killings when two young Indian tourists were beaten to death in a remote hill district.

In an auditorium in the state capital, Guwahati, WhatsApp’s lime-green logo was emblazoned on a poster under the words “Fighting Fake News” — the title of a series of workshops the company is conducting in 10 states along with the Digital Empowerment Foundation, a New Delhi nonprofit.

After screening the kidnapping video, Ravi Guria, the foundation’s deputy program director, paced onstage and asked the room how a user could have determined it was fake.

Didn’t the ersatz closed-circuit footage look too crisp? Didn’t the accompanying tales of kidnapping gangs sound far-fetched, and warrant cross-checking with official sources or news websites?

“Just by sending one forward, we become part of the system that is perpetuating fake news in this country,” Guria said. “Before sending a message, we have to think of what kind of impact will it have on the person receiving it. We cannot wash our hands of this responsibility.”

These are fresh concepts in much of India, which has more new internet users than anywhere in the world. Over the next three years, according to industry projections, the number of Indians online will increase by more than 58%, to 762 million.

Most of the growth will come on smartphones hooked up to cheap data connections — and 2 out of 3 smartphones in India today use WhatsApp.

“If you ask someone if they access the internet, they’ll say no, but they will have WhatsApp,” said Govindraj Ethiraj, a TV journalist and founder of Boom, the Indian fact-checking website that first debunked the kidnapping video in 2017.

WhatsApp’s data show that Indians use the app differently from people in other markets — as much to share stories and images as to send private messages. India has one of the highest rates of forwarded messages of any country, meaning many users are passing around content that they didn’t write but originated from somewhere else.

Take a vast pool of digital novices and a society that relishes storytelling and gossip, and add a largely hands-off approach from social media companies eager to dominate the world’s biggest remaining open market, and you get a country that is particularly susceptible to misinformation online.

“Fake news is part of our culture,” Guria said, wrapping up the two-hour workshop. “Technology has only intensified it.”

At the back of the room, Rifa Deka, a 22-year-old pursuing a master’s degree in mass communication, nodded. Her family members had seen the kidnapping video when it went viral last year, and while she didn’t know whether any of them had forwarded it, she often pointed out to her parents that sensational images flying around their WhatsApp groups had been edited or altered.

“They have definitely circulated fake news,” Deka said afterward. “Whenever they see something on Facebook or WhatsApp, like news that a religious miracle happened, they don’t Google to verify it — they just share it. A lot of times in India, we just automatically share a video because we think it’s funny or interesting, because we think that’s what WhatsApp is for.”

To cut down on potentially harmful content going viral, WhatsApp made changes to its app in India, allowing users to forward a message to a maximum of five chats at once. Company officials said forwarded content dropped by more than 25%, and recently implemented the limit worldwide.

With elections also due this year in Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines, WhatsApp’s efforts in India are seen as a test of parent company Facebook’s commitment to solving its fake news problem. Facebook announced last week that it had opened an office in Singapore to work on ensuring election integrity in Asia, to “add a layer of defense against fake news, hate speech and voter suppression.”

Since 2016, when Russian accounts used Facebook to spread fake stories during the U.S. presidential campaign, the social media giant has been accused of failing to stop organized disinformation campaigns in elections in Brazil and Mexico, of accelerating hate speech that fueled religious violence in Sri Lanka and of being used as a tool for ethnic cleansing by the army in Myanmar.

Since the mob killings, Indian regulators have warned WhatsApp and other social media companies that they could face legal action unless they act against false information. WhatsApp, with 1.5 billion users worldwide, primarily in developing countries, says it can’t block harmful content because messages are protected by end-to-end encryption — meaning they are seen only by senders and recipients.

The company has also sponsored digital literacy programs in Brazil and Nigeria, although India is the only country where it has aired TV ads.

“We believe an important way to address sharing of misinformation is to help step up people’s awareness of fake news and rumors,” WhatsApp spokesman Carl Woog said. “We’ve seen strong indication from experts that broad scale education can help in the fight against misinformation.”

Digital literacy matters because even more than other platforms, “WhatsApp is primarily reliant on users to identify misinformation,” said Sarvjeet Singh, executive director of the Center for Communication Governance at National Law University in Delhi.

Last year, WhatsApp formed a partnership with Boom, which has a hotline number where users can send suspicious messages to be verified. About 25 to 30 messages come through every day.

Operating out of a converted industrial building in central Mumbai, Boom’s dozen fact-checkers review submissions in Hindi and English. When a message appears to be spreading — surfacing on Facebook groups or even mainstream media — a fact-checker is assigned to investigate.

WhatsApp says it is exploring additional fact-checking partnerships ahead of the elections. But the scale of the problem is staggering. The roughly two dozen workshops so far have reached barely a few thousand users — while just weeks ago, the child kidnapping rumors resurfaced in southern India, using different images.

Sunil Abraham, executive director of the Center for Internet and Society, an independent think tank, said WhatsApp and other platforms need to build more educational tools directly into their apps, such as video tutorials and more obvious warnings on unverified content.

“If every forwarded message came with a little label that says, ‘This could be fake news,’ that forces everybody to consume all forwarded content skeptically,” Abraham said. “The problem is so large now that we need systemic fixes.”

The stakes are high, and not just for the elections.

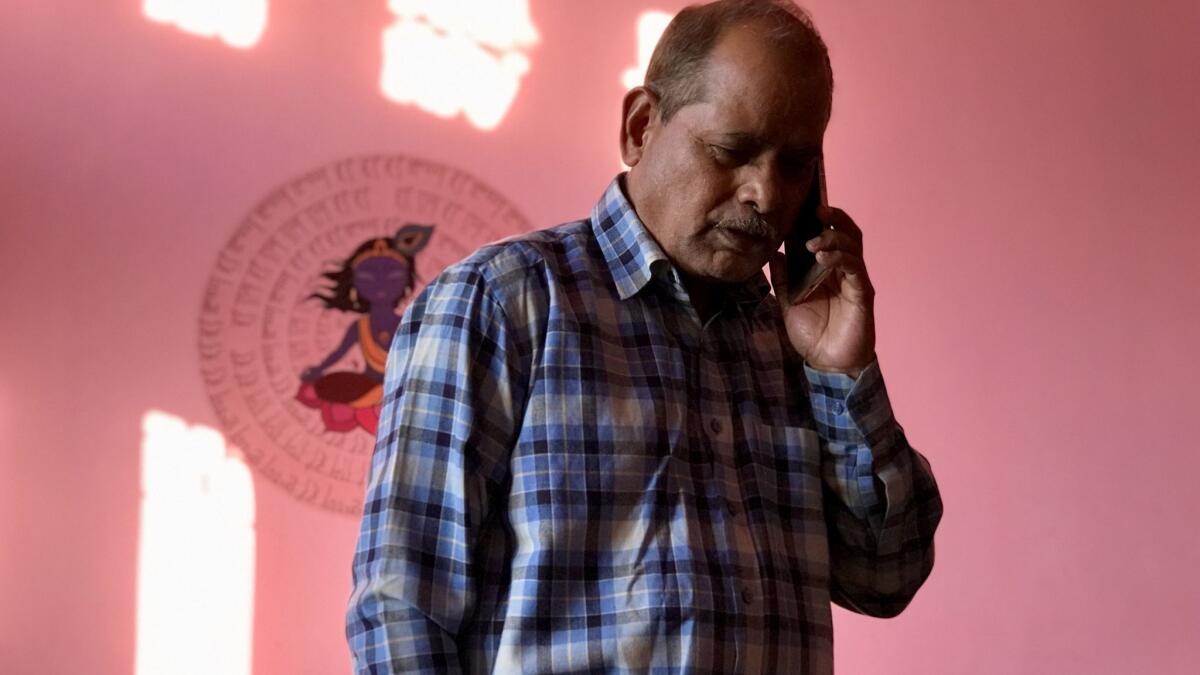

In a tidy, two-room house a few miles from where the workshop took place, Gopal Chandra Das, a retired auditor, sat in his living room next to a portrait of his son. A musician and aspiring designer with long, fuzzy dreadlocks, 29-year-old Nilotpal Das and his friend Abhijit Nath had traveled to a remote part of Assam last June when some agitated villagers pegged them for kidnappers, police said.

A mob gathered and attacked the pair with sticks and planks. Some recorded the beating on their phones. In one clip, Das is seen pleading: “Please, don’t kill me. I am Assamese.”

In the hours after their deaths, that video, too, went viral. The evidence helped police arrest 47 people, who are now facing trial for murder.

His youngest child’s fate cemented Gopal Chandra Das’ belief that social media companies can be “enemies of society” unless they work to prevent misuse of their technology.

“What happened has happened,” Das said. “But WhatsApp and Facebook need to minimize fake news. What we went through — it should be the last incident like this.”

Shashank Bengali covers Southeast Asia for The Times. Follow him on Twitter at @SBengali

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.