Scholar fights to keep Jewish artifacts from returning to Iraq

WASHINGTON — Harold Rhode still recalls the euphoria he felt a decade ago after finding thousands of dripping, moldy artifacts of Iraq’s once-vibrant Jewish community in the flooded basement of Saddam Hussein’s intelligence service headquarters in Baghdad.

“How do you describe it? An enormous elation, a deep connection, but also shock: Why would this be here?” says the 64-year-old former Pentagon official, an Orthodox Jew who discovered the purloined archive in the bombed-out building days after he arrived in the Iraqi capital with the U.S. invasion force in the spring of 2003.

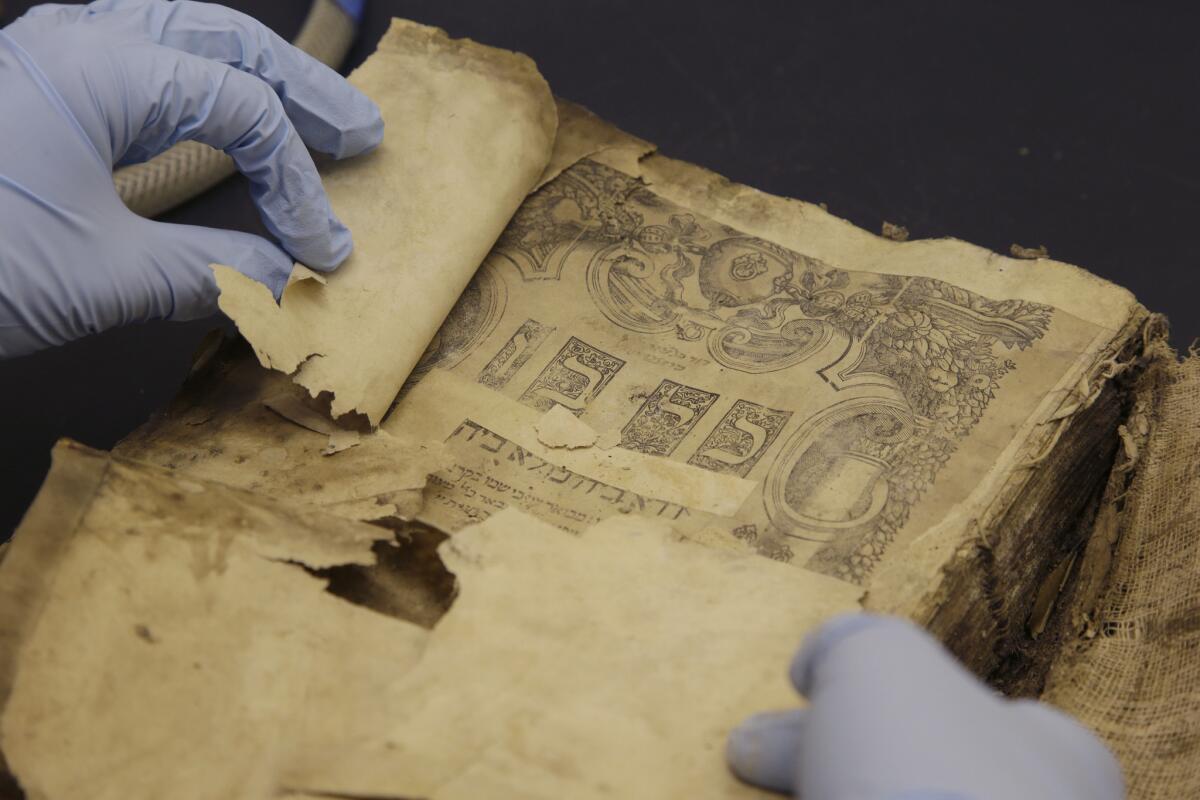

People who saw him at the time recall that Rhode, a disheveled, rotund scholar of Islamic history, was nearly overcome with emotion as he rescued the waterlogged books, personal papers and sacred texts, including a 400-year-old Hebrew Bible, all of which seemed to be a link to the ancient — and mostly dispersed — Jewish population of Mesopotamia.

But like the arc of the U.S.-led war in Iraq, Rhode’s involvement with the Iraqi Jewish archives has progressed from exhilaration to disillusionment and recrimination.

Since he arranged 10 years ago for the collection to be brought to the United States in metal shipping containers, on which he had scrawled “RHODE” and “TORAHS” in big letters, the books and documents have been carefully cleaned of mold and grime, preserved and digitally photographed by experts at the U.S. National Archives.

When summer comes, however, they are to be returned to the Iraqi government, an ending that Rhode likens to giving the personal effects of Jews killed in the Holocaust back to Germany.

Rhode has launched a campaign to halt the transfer, joined by a growing number of American Jewish groups and members of Congress, who argue that the materials belong to the Iraqi Jews they were taken from and their descendants, not to Iraq’s government.

For years, intelligence operatives working for Hussein and his predecessors apparently seized papers from synagogues and Jewish families, in periodic crackdowns or before the families would be allowed to emigrate.

Why the materials, most of which document relatively mundane activities of Iraq’s Jewish communities, were kept for decades in the security service headquarters is a mystery. Rhode attributes it partly to Hussein’s mania for getting back at Israel.

“By Saddam taking this material, it was like he was personally humiliating the Jews of the world and Israel,” Rhode says. “So now are we going to return it to them?”

Iraqi officials say the current government has no connection to abuses Jews suffered under Hussein. They say they want the materials returned, as U.S. officials promised to do when they were taken out of the country for preservation, in order to document the country’s rich Jewish history. Several Iraqis are being trained by the National Archives in proper handling of the materials, and U.S. officials say Iraq has promised to carefully protect the archive and make it publicly available.

But opposition in the U.S. to that effort has grown, due in no small part to Rhode’s efforts.

Although unfamiliar to most of the public, Rhode was an architect of the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq from his desk at the Pentagon, where he spent 27 years as an in-house expert on the Middle East. He became a sounding board for top George W. Bush administration officials and neoconservatives who argued that toppling Hussein would transform the region in a manner that meshed with American interests.

Assigned to work for the U.S. occupation authority, Rhode made his way to Baghdad in the days after Hussein’s fall, in April 2003. According to a lengthy written account he has posted online, Rhode learned about the Jewish archive in the intelligence agency from Ahmad Chalabi, the controversial Iraqi exile whom some in the Bush administration wanted to install as Iraq’s new leader. He, in turn, had heard about it from an Iraqi defector.

After enlisting a team of U.S. soldiers who were supposed to be looking for weapons of mass destruction, Rhode went to the intelligence headquarters to search.

“We went around to the building’s main entrance and descended only halfway down a basement staircase, blocked by water which had risen about halfway up,” he writes. “The WMD team then proceeded down the hall, found the Jewish section, and carried out religious books and a tiq,” a box made of wood or metal that Jews in the Middle East and North Africa use to hold Torah scrolls.

With looters everywhere, Rhode said, he persuaded Chalabi to provide small pumps to drain the water from the basement and hurriedly got money from a Wall Street executive to pay Iraqis to carefully remove the papers and lay them in the sunlight to dry.

Rhode’s efforts to get the Pentagon and the State Department to help salvage the documents were ignored until he or intermediaries reached out for help to top Bush administration officials, he says. At his urging, Richard Perle, one of his former Pentagon bosses, called Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, Rhode says. Rhode also asked Natan Sharansky, the former Soviet dissident and Israeli government minister, to ask Vice President Dick Cheney to help the project.

A document released by Rumsfeld as part of his memoirs supports Rhode’s account.

“I am told somebody found a cache of documents in the headquarters of the Iraqi Intelligence Secret Police in Baghdad … and that some portion of them relate to the history of the Jewish community in Iraq,” Rumsfeld wrote in a May 31, 2003, memo that went to all the top U.S. military and civilian officials in Iraq.

“Could you please have someone look into that … and what we’re doing about it, if anything.”

The next day, Rhode says, he had all the help he needed, including several massive pumps and a refrigeration truck in which to keep the soaked documents frozen, a way of preserving them for eventual restoration.

A small portion of the collection, which includes 2,700 books and 10,000 documents, recently went on display at the National Archives building in Washington and will move on to New York.

Rhode’s role in saving the papers is not mentioned in the Archives exhibit, but the display includes several items supporting his account, starting with a dozen metal trunks used to move the collection out of Baghdad, each prominently emblazoned with his name. A picture of the recovery effort shows him carefully carrying soaked documents out of the basement while wearing a gigantic rubber suit, but bears no caption identifying him.

Among the documents are a 200-year-old Talmud from Vienna; a 19th century Passover Haggadah, published in Baghdad and edited by its chief rabbi; a copy of “Ethics of the Fathers,” published in Livorno, Italy, in 1928 with handwritten notes in Hebrew; and a collection of rabbinical sermons made in Germany in 1692.

Most of the papers are routine correspondence from the 20th century, lists of male Jewish residents in Iraq, school records, financial records, applications for university admissions. They sometimes hint at the decline of Iraq’s Jewish community, which numbered 50,000 in Baghdad alone in 1910 but eventually shrank to just a few.

State Department officials say the plan is for the collection to be returned to Iraq late next summer. But the campaign to prevent that seems to be picking up steam.

In a statement released last month, more than 40 American Jewish groups said they were “deeply troubled” by the prospect of the documents being returned to Iraq, citing “uncertain conditions” there. They called for the books and papers to be provided “to synagogues of Iraqi Jews in the U.S. and elsewhere to be used and their sanctity protected.”

At a hearing last month before the House Foreign Affairs Committee, lawmakers grilled Brett H. McGurk, deputy assistant secretary of State.

He affirmed that the U.S. was committed to the “safe and rightful return of these artifacts” but also acknowledged that “we have heard loudly and clearly the concerns” of the Jewish community. “We’ll see what we can do.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.