Israel celebrates blessing of the sun

Our attire was about as casual as it can get for a religious celebration.

At dawn Wednesday, about two dozen runners in shorts and T-shirts charged up a hill and stopped on a ridge overlooking the Elah Valley, the biblical site of David’s triumph over Goliath.

Across this spectacular vista at this very moment, according to Talmudic calculations, the rising sun was returning to the exact position it occupied at the time of Creation, repeating a phenomenon said to occur every 28 years.

Prayer sheets were distributed, and Ari Ferziger, a lean, athletic corporate lawyer, called the group to attention.

“You’re supposed to look at the sun and notice it but then look to the side,” he instructed, gesturing into a cloudless sky. “We’re not worshiping the sun. We’re worshiping its creator.”

With that, the Beit Shemesh Running Club began its Birkat Hachamah, or blessing of the sun, a joyous ritual of early morning praying, singing, clapping and dancing replicated Wednesday by observant Jews at outdoor venues across Israel and the world.

The club’s six-minute observance was coupled with an eight-mile run along dirt trails in the Judean hills around Beit Shemesh, one of Israel’s premier hiking and biking spots. The city’s name, Hebrew for “house of sun,” is assumed to have been inspired by sun god worship during the early Canaanite period, about 3000 BC.

I had asked about the event, and Chaim Wizman, the club’s founder and coach, had invited me to take part. As a competitive long-distance runner, I couldn’t resist. And as an American Gentile, I welcomed the chance to share this passion, and my attraction to milestones, with Israeli Jews.

Besides, a trail-running religious event seemed a newsworthy example of how times have changed since the last blessing of the sun, on April 8, 1981.

Thanks to the Internet and alarm over global warming, what was once a relatively simple and arcane celebration associated with black-clad ultra-Orthodox Jews has become more widespread, and infused with environmental and New Age messages.

“What is it we’re celebrating, essentially?” Wizman asked during the run. “We’re celebrating the pristine state of nature at the moment of Creation, right? The world was created that way, you know, and we blew it. Now, the objective of mankind, in the Torah’s view, is to re-achieve that pristine state.”

Wizman speaks with the authority of an ordained rabbi. Like most of his teammates, he belongs to the modern Orthodox stream of Judaism, religiously observant but more accommodating to secular influences. The team admits women, and a few joined Wednesday’s run.

For this band of mostly middle-aged runners, hitting the trail affirms a spiritual connection to nature and the land of Israel, to which many of them have immigrated. They deemed it an ideal way to mark Wednesday’s celebration, which happened to coincide with the eve of Passover. Similar themes cropped up at other sun-blessing venues in Israel, including an arts, music and “healing” festival in the northern town of Safed.

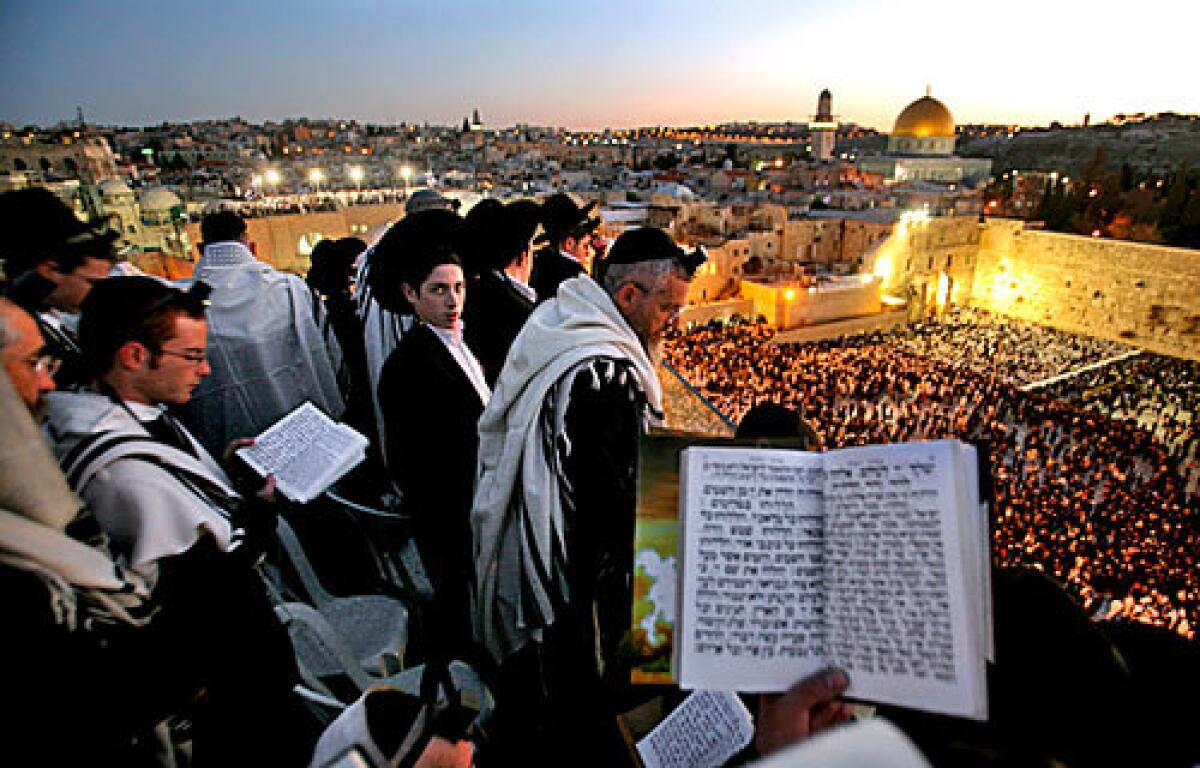

Even so, tens of thousands of worshipers crammed the traditional site, Jerusalem’s Western Wall. And an observance in the West Bank turned violent as Palestinian rock throwers clashed with Jewish settlers greeting the sun in Bat Ayin, where last week a Palestinian killed an Israeli teenager with a pickax. Israeli soldiers intervened Wednesday and opened fire, wounding 12 Palestinians.

By contrast the scene in Beit Shemesh was idyllic.

The running course meandered past fields of wildflowers, vineyards, fruit orchards, an olive grove planted eight centuries ago, a honey farm stocked with beehives, Crusader-era ruins, and biblical battlefields where the Israelites fought the Philistines. We also passed a heavily guarded military installation and what my hosts suspect is a nuclear missile silo.

There was no danger of getting lost. Among the group was Lt. Col. Ophir Dor, who designs global positioning systems for the Israeli military.

Along the way, we shared reflections on our own lives: what had changed over the last 28 years and what we envisioned for the year 2037.

“Guys, just think how old you’re going to be next time this happens,” Wizman told us early in the run.

“In 28 years, hopefully I’m speaking Hebrew,” said Rich Levitas, a 49-year-old American-born Web designer who is struggling with the language a decade after moving here.

“Let’s not get carried away,” a fellow runner quipped.

“And also in 28 years, maybe I can finally break three hours in the marathon,” added Levitas, whose best time for the 26.2-mile race is 3 hours, 4 minutes.

Rael Strous and Johnny Burg were 10th-graders from South Africa in 1981 when their tour group insisted on joining the sun blessing at the Western Wall on its final morning in Israel. The group raced to the airport afterward, barely making the flight home.

Years later, Strous and Burg found themselves living in the same neighborhood of Beit Shemesh, working as a psychiatrist and a lawyer, respectively.

Yitz Corn, a 43-year-old information technology consultant, reflected on the intergenerational passage of life and his father’s death a few years ago at age 76. He said he had taken up running shortly afterward, with the hope of living longer, and had since lost 60 pounds.

“My son is 14,” he said. “Hopefully I’ll be there for him at the next Birkat Hachamah, when he’ll be almost 43.”

Like most everyone blessing the sun this time, Strous is aware that the ancient calculation of its 28-year cycle has been proved inexact. But to him, it’s close enough to justify the tradition.

“You long for something that comes every so often, a phenomenon of belonging together at a cosmic level,” he said during our charge up the hill. “That kind of event challenges us to grow, to feel part of something bigger. That’s the essence of it: being part of something greater than yourself.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.