In southern Madagascar, local custom presses girls into sex at a young age

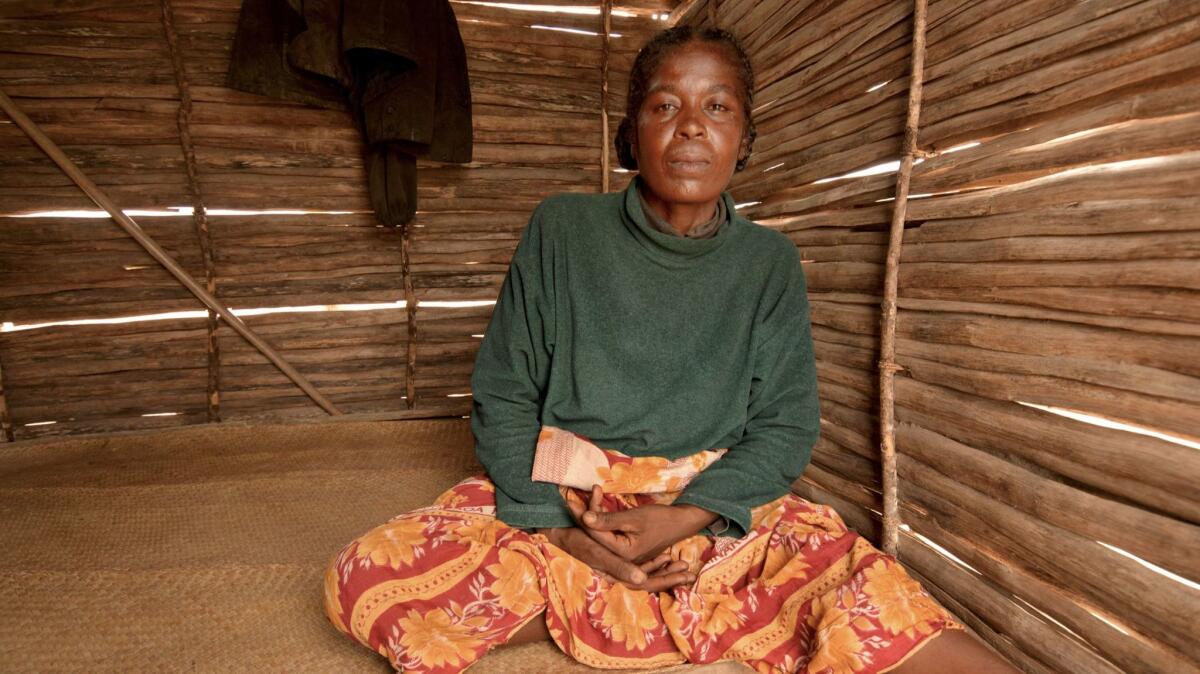

Hunger often keeps Valopee awake at night, as do the men talking and laughing outside the door of her bare wooden hut in this southern Madagascar village.

They wait until late, hoping for sex. She lies on her hard floor with no mattress, wishing they would go away.

Under local custom, single girls and women in some ethnic groups here are expected to offer sex to village men and passing strangers. They can brush off some, but it is shameful to refuse a visiting outsider, and difficult for girls to resist determined older men.

Many girls are moved out of cramped family houses by their mid-teens and given their own small huts near the family home, a rite of passage in preparation for marriage.

“Parents want to show the community that, ‘My girl is ready,’ because the parents think she has become an adult,” said Meta Paubert, a Seattle-based Tandroy woman who runs Nofy i Androy, a nongovernmental organization working in southern Madagascar to help girls stay in school.

The tradition, preserved by several ethnic groups, leaves these single girls prey to men who surround their huts at night and suitors who lose interest as soon as girls get pregnant.

“They just want them because they’re little girls, fresh,” said Paubert, who was a single teenage mother in southern Madagascar, but became one of the few to return to school and go to university. “They come to you at the age of 11, 12, 13 saying, ‘I like you, I’ll talk to your daddy. Will you be my wife?’ Then when you have a baby they disappear. They can get a younger one. And the whole village looks down at you. You’re on your own.”

The long-term result: startling numbers of single mothers with many children conceived with different men who do not help raise them. The women and their children are the poorest and hungriest people here in Madagascar’s most impoverished region.

Although the single women and girls, known as ampelatovo, a Malagasy word meaning “little girl,” may take payment from the men they allow into their huts, villagers do not consider this prostitution.

Valopee, bone-thin from years of drought, poverty and hunger, has no second name, does not know her age and is raising six children on her own. She agreed recently to have sex with “a very old man” from another village, but only after some bargaining. He offered less than a dollar but ended up paying her $1.25, enough to buy 5 pounds of rice.

Paubert remembers the pain of being a teenage single mother, “and no man wants you anymore because you are done, you have a baby. You walk and everyone, whether adult or child, they yell at you about how bad you are, how ugly you are....”

The country has one of the highest rates of teen pregnancy, according to the United Nations, and one of the highest rates of child marriage, with 41% of girls married by 18.

UNICEF and humanitarian agencies have long struggled to end child marriage, but cultural customs are often difficult to change in rural communities. For decades, the U.N. has urged countries to modify traditions that hurt women and children, but practices such as female genital mutilation, forcing widows to marry brothers-in-law, child marriage, virginity testing and witch-killing endure in some parts of the world, including Africa.

From the traditional Malagasy perspective, it makes sense for parents to move girls out into their own houses to become sexual beings, according to anthropologist Jeffrey Kaufmann, an expert on southern Madagascar. He said it is seen as preparing them for life, marriage and their own children. The girls’ houses are placed to the east of the main house, as a sign of respect to the ancestors who are believed to influence the luck or misfortune of the living.

“It is not a sign of moral decay or the plight of a victim,” he said. “A virgin is a lost cause in this society we are discussing. Such a being is not equipped to take on the world she is entering. She needs to learn about sex, how to bond a man or men to her and how to make decisions on her own that will prepare her for life.”

Valopee, who was about 13 when she was moved out of her mother’s house, said she would like to see her community abandon the tradition.

She had one love. In 2006, she met a man who stayed for seven years and fathered several of her children. But he abandoned her to marry someone else.

“I don’t feel anything for him now,” she said, shaking her head.

When Jocelyn Rasoanakambana moved into her own house at age 18, she felt uncomfortable with the expectation that she would sleep with different men.

“I disliked it because there were many and they would fight with each other,” she said. “I only feel happy with one man.”

“Sometimes I accept it just to buy food and water,” said Rasoanakambana, 30, a single woman who lives in Ikopoky village with six children from three fathers. “I have to accept my cousins or if there’s a newcomer to the area I should accept him, otherwise it’s a shame for our family.”

One of her cousin’s husbands comes for sex once a week and gives her a small amount, anything from 60 cents to $1.50.

With so many children, she says it is unlikely she will find a husband now.

“In most cases, men dislike feeding children who are not their own. I don’t know what will happen to me in the future,” she said. “I’m living in the poorest situation now, the worst situation.”

Some men who benefit from the tradition fret when it harms their daughters.

“It’s very good for the men because if [a girl] is ampelatovo, I have no problems to go with her,” said one elderly farmer, Veza, who goes to one of his young relatives for sex. “The tradition is very bad for the single woman, but she has no choice because she is waiting for someone to marry her. In our tradition, if she’s single, she’s not respected. If she’s married, she is respected, so to be a single woman is not good.”

Like most, he is fatalistic. His own daughter remains unmarried.

“She is still my daughter even though she’s not married and even though she has this name, ampelatovo,” he said sadly. “The only thing I know is that she is human like all of us. She has her right to exist.”

In Madagascar there are other harmful traditions. Teenage girls attend markets where they are paid to be temporary wives for a few nights. Some communities abandon twins after birth believing them to be unlucky. There are taboo days when people cannot work, which means less to feed their children. In some communities it is forbidden to build latrines, leading to high rates of open defecation that spreads disease.

Then there is the funeral tradition of the Tandroy tribe, which leaves communities impoverished. A man holds all his worldly wealth in his cattle, but when he dies they must all be slaughtered and his house burned down to prevent its inhabitation by spirits. Families often work for months to pay for the funeral feast and build a huge tomb with the horns of his slaughtered bulls arrayed on top.

By doing so, families believe the dead ancestors will bless them and not bring ill fortune. The practice burdens families with large costs and no inheritance.

Kaufmann said it made sense to Malagasy people to do everything possible to keep ancestors happy, including blood sacrifice of cattle — a man’s most prized possession — at funerals.

But fear of angering ancestors complicates efforts to modify harmful cultural practices.

The Ifotaka mayor, Tompotany Remanintsy, said the funeral tradition has left many too poor to feed their children or send them to school.

“It’s high time to change it because it’s really a barrier to development.”

Zafesoa, mother of eight and one of the poorest ampelatovo in Kobokara village, was born 55 years ago to a wealthy man. She was 12 when her grandfather died and the family cut a great tree to form a casket. Many people came to the enormous funeral.

“My father had many cattle but when his father died he used all the cattle for the funeral and he was left with nothing.” A month later both parents moved away looking for work, taking only their youngest child and leaving seven behind.

“I was crying. I was heartbroken. I never saw them again.” The children had little to eat, and after a year the girls moved into their own small huts, becoming ampelatovo.

Her one-room wooden hut is bare except for a jacket hanging on one wall. She makes less than 30 cents a day as a laborer clearing fields of prickly pear cactus.

“Now I’m poor. It’s really hard for me to support my children. I don’t blame my father for his decision but the thing I know is that it ruined my life by lavishing all the wealth on that funeral.”

She would like to see cultural traditions change, including ending the ampelatovo custom. Men benefit, she says, but not women.

“If the men would ever join us to change this way of life,” she said, “I think it could change.”

To read the article in Spanish, click here

This story was reported with a grant from the United Nations Foundation.

Twitter: @RobynDixon_LAT

ALSO

A Senegal-based humanitarian group helps African communities reject harmful practices against women

When a Kenyan woman took up a man’s job, people said she’d be cursed. She persevered

In Mexico, they made a new American dream — minus their kids

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.