Pakistanis trickling back to shattered towns

A small number of Pakistanis have begun leaving refugee camps and trickling back to this hamlet tucked away in the verdant ridges south of the Swat Valley.

When they arrive in Ambela, once a town of 11,000 people, they find a place made largely unlivable by war. Phones don’t work. Electricity has been off for weeks. Wheat and tobacco crops, the town’s livelihood, have rotted. There are only about 2,750 people living here now.

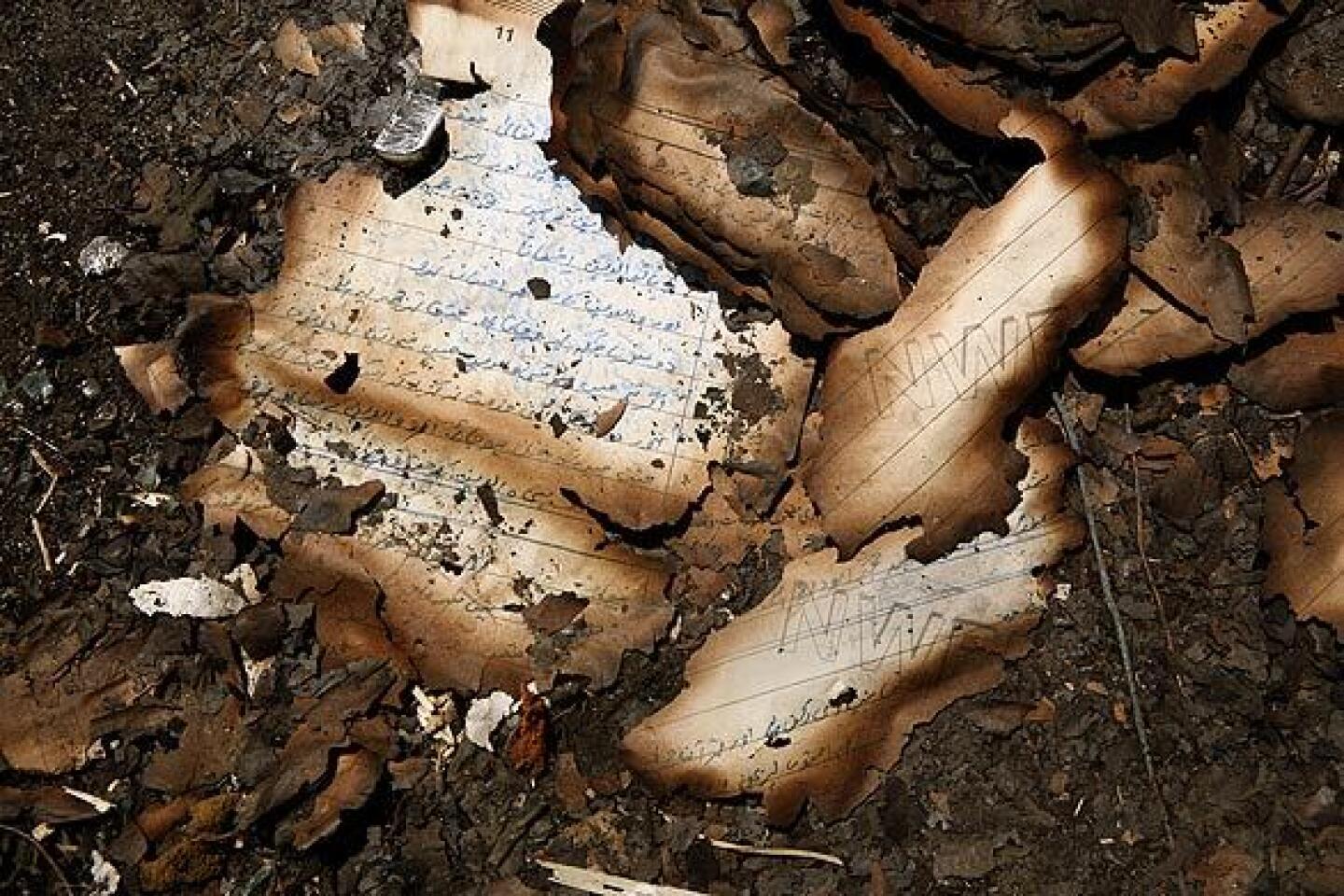

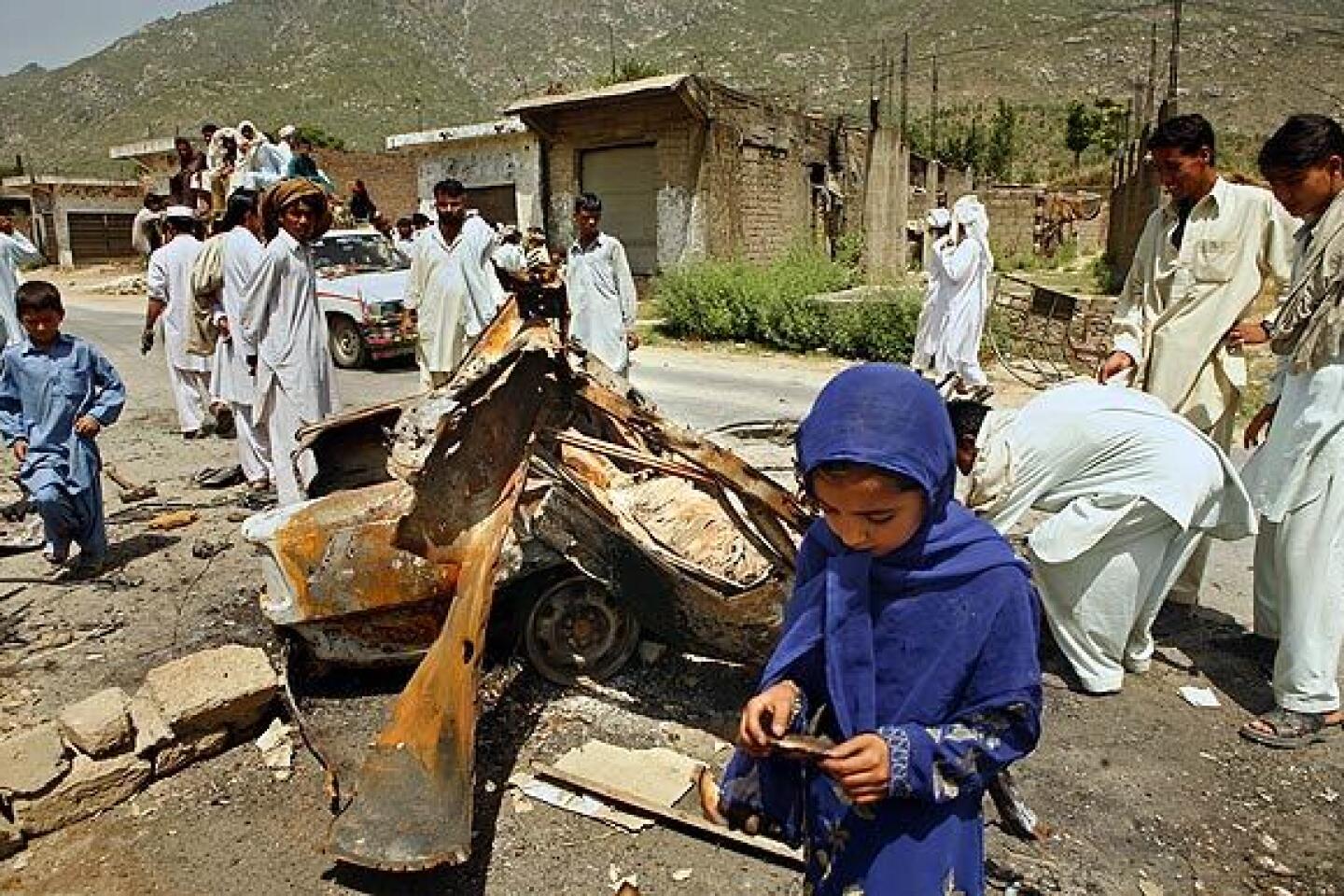

Near shuttered storefronts pocked with bullet holes, a group of residents scavenge burned-out car frames for scrap metal, piling shards onto a wheelbarrow. For now, it’s the only way to make a bit of cash.

“We want to fix up our broken town,” said Mohammed Salim, 41, a wheat farmer and one of the men picking over the scorched metal. “But it was the government who destroyed it, so when the government compensates us, maybe more people will come back. So far the government has given us nothing.”

Nearly two months after the offensive was launched to oust the Taliban from northwest Pakistan, people who fled the fighting are finding themselves forced to choose whether to endure the misery of cramped, poorly organized displacement camps amid torrid heat, squeeze in with relatives or return to war-scarred towns lacking everyday basics.

The government has been urging its citizens to return to their homes in villages like this one in the Buner district, just south of Swat, where fighting against Taliban militants has largely subsided and security forces maintain order.

The top government administrator in Buner, Yahya Akhundzada, said Friday that the return of people to secure areas would contribute to the defeat of the Taliban.

“When they come back,” Akhundzada told reporters on a government-organized trip to Daggar, “people will be more confident and that’s how we can eliminate the militants.”

But those returning are encountering the same kinds of obstacles seen by Salim -- crippled infrastructure, a lack of drinking water, ruined crops -- that stifle attempts to rebuild the economy.

And residents also still face violence. Every night in Ambela, bursts of gunfire are heard as troops try to root out small pockets of Taliban fighters holed up on the forested hillsides skirting the village.

“I brought back my family when curfew was lifted,” said Bakht Saeed, 55, a farmer who, along with his wife and nine children, had taken shelter at a relative’s house in Swabi. He returned to Ambela on May 23. “But that night when the military began shelling in the hills, it terrified my wife and kids. My 7-year-old son, Javed, wept and cried, ‘We want to get out of here!’ ”

The next day, Saeed’s wife and children returned to Swabi.

The plight of displaced villagers underscores the challenges the government faces as it prepares for its next crucial task -- reconstruction.

The International Crisis Group warned in a recent report on the Swat situation that the region could devolve into the same lawless, warlord-dominated economy found to the south in Pakistan’s tribal areas along the border with Afghanistan if the government doesn’t act fast to get the farms and businesses back on their feet.

In Swat, once a tourist haven, that means reviving more than 400 hotels and restaurants closed when Taliban fighters took control of the district in 2007. In adjacent Buner, it means restoring an agricultural sector that was the economic backbone for a population of 600,000.

“The displaced are anxious to return to their businesses, homes, fields and orchards,” the International Crisis Group report says, “but any measures to ensure their survival must be accompanied by clear signals that the government is committed to rebuilding a shattered economy.”

In a visit to Pakistan in early June, the U.S. special envoy for Afghanistan and Pakistan, Richard C. Holbrooke, said he was told by Antonio Guterres, the United Nations high commissioner for refugees, that reconstruction in the conflict zone could cost $500 million to $1 billion. The international community, Holbrooke said, would have to shoulder the cost.

Many Pakistanis remain skeptical about any rebuilding after a military offensive. Last year, troops launched an offensive against the Taliban in Bajaur, a region in the tribal border areas. By February, the government had declared the region clear of militants and authorities promised to rebuild villages, residents said.

“There have been many promises, but they haven’t done anything,” said Tahseel Khan, 36, a farmer from the village of Salarzai in Bajaur whose family has been living in a camp outside Peshawar.

In at least one case, the government will be expected to rebuild a town that has all but disappeared. Fighting between the Taliban and troops using helicopter gunships razed almost all of the farming town of Sultanwas in Buner, said Afsar Khan, the mayor. Amid a wasteland of rubble, eight homes are left in a town where 10,000 people had lived, Khan said.

“If you go there, you would not recognize Sultanwas,” Khan said in Peshawar, the capital of North-West Frontier Province, which encompasses the Swat and Buner districts.

Especially worrisome, Khan said, is that provincial and federal government officials have yet to produce a plan for rebuilding Sultanwas. If authorities do not act soon, he warned, the Taliban and other Islamic extremists could exploit the government’s inaction and muster new support among the people.

“If there’s little or no reconstruction, the Taliban will come to the people and say, ‘We told you that if the government comes, there will be destruction,’ ” Khan said. “So reconstruction is very important, so that the Taliban doesn’t regain a foothold in Swat and Buner.”

Ambela was one of the first towns where fighting broke out as troops mounted an all-out incursion into Buner, Swat and nearby districts to rid the area of the Taliban fighters. The government decided to send troops into northwest Pakistan in late April after the Taliban reneged on a peace deal in which they were to lay down arms in return for the imposition of Sharia, or Islamic law, in Swat.

Fighting in Ambela had subsided by mid-May, and shortly afterward, people, particularly wheat farmers, began to return.

Sher Akbar, a former lawmaker from Ambela, said nearby marble factories need electric power, as do pumps that irrigate thousands of acres of wheat, tobacco and fruit orchards.

“The damage here is in the millions of dollars,” said Akbar, a member of an offshoot of the country’s ruling Pakistan People’s Party. “There’s no action by the government to restore utilities here. How will people survive? They won’t come back because there’s no economic activity. There’s no life here.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.