Keeping track of South Africa’s young democracy

South Africa and I have a history, one that goes beyond the headlines.

I arrived here as The Times’ bureau chief in 1988, when college campuses back home were pulsing with anti-apartheid protests, to cover what would turn out to be the last years of the black freedom struggle -- bombings, funeral processions and brutal clashes with police. My phone was tapped by the government and, during one township visit, I was dragged from my car by armed young “comrades” from the African National Congress, saved only by my laminated press pass.

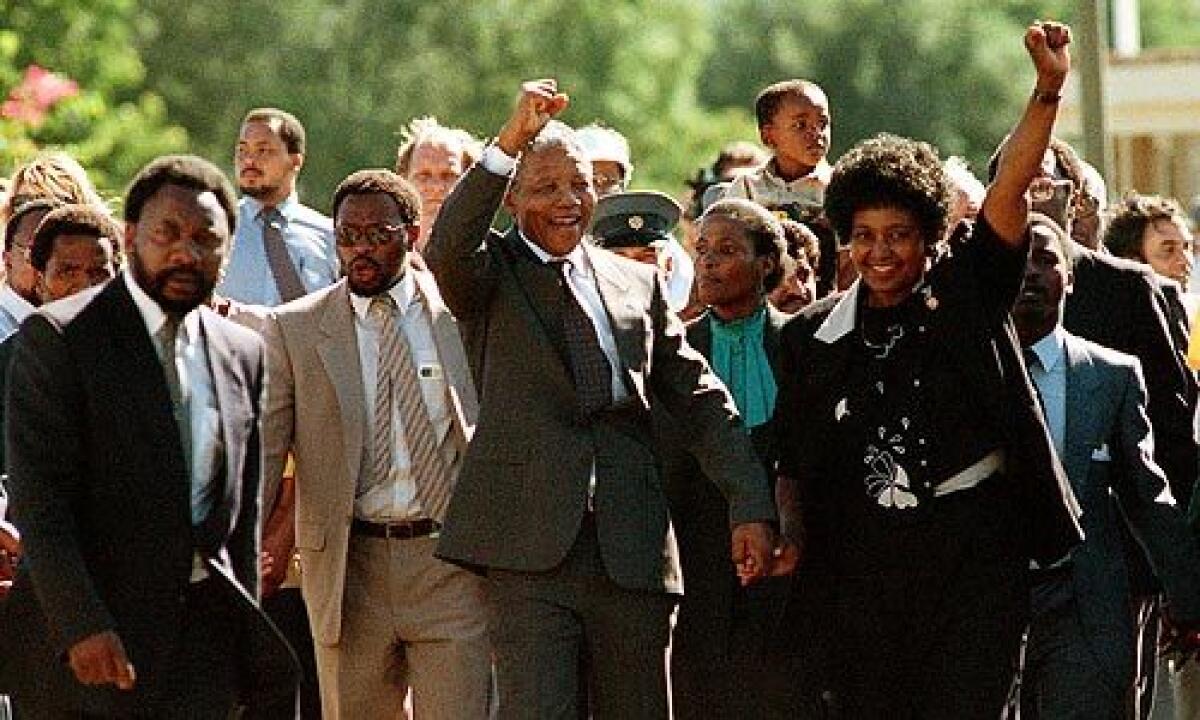

Our children were born here, our daughter just a toddler when I watched Nelson Mandela walk free from prison. Our son arrived later that year, on the eve of another historic moment -- the first round of negotiations between whites and blacks for a new constitution.

Mandela’s release in February 1990 was a watershed moment, and those of us there that day, like the millions watching around the world, had the palpable sense that things would never be the same. Although it touched off a new burst of violence, the country survived four more years to hear Mandela, inaugurated as president, promise to build a “rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world.”

By then, our family had moved on to another posting, in Paris, and eventually to Los Angeles. But I’ve returned to South Africa frequently on reporting assignments and, over the years, watched it grow into a multiracial nation with economic opportunity, democratic decision-making and the respect of the world.

When I returned again recently, I took my 17-year-old son, Kevin. As we traveled the country, we reconnected with friends and many of the people I had interviewed over the years. I wasn’t sure what we would discover in our journey, or how it would look through the eyes of my son, who hadn’t been back since he was a toddler.

Was South Africa living Mandela’s dream?

Fancy new shopping malls glitter like jewels on the northern fringe of Johannesburg, and construction cranes preside over the skyline. Suburbs there, once the legal preserve of the white minority, have swelled in size and diversity. But high crime rates have driven more suburbanites into new gated communities, redoubts where white and black children clatter down safe streets on skateboards.

Kevin and I stopped for a look at our former rental home in one of those suburbs and found a fortress: 10-foot walls have replaced our chest-high ones. Across the street was a private security company’s new guard station.

A 10-minute drive away, at Morningside Clinic, Ronald White, our obstetrician, emerged from his office to greet us. “Nice to see you again,” he said to Kevin, as if he had seen my son just last month, rather than when he was just a few minutes old.

White lamented the number of doctors who have emigrated to Australia, Europe and the United States. “So many of us are leaving,” he said. But the view outside his office told a different story: Where once there was a farm, a major expansion of the clinic was underway, and the doctor acknowledged that the area was booming.

“A colleague and I wanted to buy the Harley-Davidson dealership up the street about 10 years ago,” White said. “But they wanted 80,000 rand [about $8,000] and we said, ‘Man, that’s too much.’ ”

“It’s worth half a billion today,” he said, laughing. “That’s why I’m still working.”

“People are always saying that it’s bad in South Africa today,” the doctor’s white receptionist said, “but it doesn’t feel so bad. And some of the blacks are doing quite well.”

Among them is Zwelakhe Sisulu, a onetime newspaper editor and son of the late anti-apartheid fighters Walter and Albertina Sisulu. He was imprisoned in the 1980s for criticizing the white government, and I remember delivering care packages to his family in Soweto from his American journalist friends.

After the 1994 elections, Sisulu became head of the South African Broadcasting Corp., which used to be the mouthpiece of apartheid, and today runs a private investment group, serves on corporate boards and has homes in a wealthy Johannesburg suburb and on the waterfront in Cape Town.

As he put it: “Black people . . . are serious players in business today. A political leadership, but also a business leadership, is important in a young democracy.”

Another close friend, Thami Mazwai, then the city editor of the Sowetan newspaper, also now lives in a formerly all-white suburb. Mazwai and I had met in my early days in South Africa, and over the ensuing years I came to value his friendship as well as his astute analysis of the rifts in the anti-apartheid movement.

After the end of apartheid, Mazwai ran a group of black financial magazines. Now, he’s at the University of Johannesburg, as director of its small-business development program.

Over dinner at Mazwai’s home, we talked politics and sports. His political allegiance once lay with the Pan-Africanist Congress, the ANC’s anti-apartheid rival, and although he acknowledges that the ANC-led government has addressed some of the needs of the impoverished black majority, he thinks it can do more.

“There are too many black millionaires, while others don’t have clean water,” he said.

But Mazwai has watched with delight as some of the old racial barriers, especially in sports, have fallen. Athletic allegiances, like so much else in South Africa, once fell along racial lines -- blacks favored soccer, while the white sport was rugby.

Mazwai himself remains a devoted fan of Soweto’s powerful Orlando Pirates soccer team. To his amusement, though, his teenage son, who goes to a multiracial boarding school, has become such a rugby fan that he refused to come home during a recent break because he wanted to see the school match.

Blacks outnumbered whites 5 to 1 when we left South Africa 15 years ago. Today, the ratio is about 8 to 1, and the 5 million whites are a mostly silent minority, having accepted that their lock on political power is gone. For some, it has been a relief. The international sanctions are gone, the economy is intact, and when they travel abroad, they feel a welcome they never felt during the apartheid era.

But they keep a close eye on the ANC, which won nearly 70% of the vote in the last elections. After a power struggle within the ANC between populist Jacob Zuma and President Thabo Mbeki, the latter stepped down late last year and a caretaker president was installed. If the ANC wins a majority in elections later this year, Zuma, who lost his job as deputy president in 2005 amid allegations of corruption, is likely to be the new president. Whites, and many middle-class blacks, are worried that he’ll move away from Mbeki’s pro-capitalist policies, scaring off investors and endangering the nation’s economy.

Near Stellenbosch, the heart of the wine region outside Cape Town, Kevin and I drove to the farm home of Hennie and Evelynne Durr. I had met the Durrs 20 years ago, when I wrote about the generational split in white Afrikaner families over apartheid. Their college-age daughter, Leslee, had been thrown out of elite Stellenbosch University for leading an anti-apartheid protest, mortifying her parents.

Later, when the ANC came to power, Hennie Durr was deeply worried about the appointment of Trevor Manuel, one of the country’s most strident anti-apartheid leaders, as minister of finance.

On my latest visit, Durr was again worried -- this time that Manuel, whom whites have hailed as a sober-minded steward of the economy, might step down now that Mbeki had resigned.

“If he leaves,” Durr said, “I don’t know what will happen to the economy.”

When I first met Danny and Gwendoline Maimane in 1992, they were dreaming of a chance to escape their matchbox house in Soweto, the sprawling black township and onetime home of Mandela, for the safety and serenity of one of Johannesburg’s white suburbs.

In Gwen’s imagination, her new house would have a security wall, a maid’s quarters out back and be dusted with the scent of freshly cut flowers from the garden. It would be “a very quiet place,” she said back then.

The Maimanes never got the suburban oasis. In the end, they decided to stay in Soweto, and added seven rooms to their matchbox. Few streets were named in apartheid-era Soweto, but theirs now has a sign and a name -- Khoali Street.

“Everybody has wishes and dreams, and I thought I would have long ago left the township,” Gwen said. She was curled up with Penny, their Jack Russell, on her faux-leather sofa. “Now I realize I couldn’t tolerate a very, very quiet place. I need a neighborhood.”

The Maimanes have a lot of company. Many in Soweto had expected a huge exodus from the township with the end of apartheid, and some, like Sisulu and Mazwai, did leave for the suburbs. But more than half of middle-class blacks still live in townships today -- most by choice. In a survey of township residents last year, four of five said they were more likely to continue living in the township now than they were a year before.

The face of Soweto, population 1 million, has changed significantly since the end of apartheid. The ANC-led government has extended water and electricity to many of the townships and squatter camps, and a home-building program is underway.

The Maponya Mall opened a year ago in Soweto, and its 180 shops and restaurants would not be out of place on Los Angeles’ Westside. A food court, under a towering glass atrium, features everything from sushi to Big Macs. Even on a weekday, the mall was filled with shoppers

But money is tight for many in the township, especially since the global financial meltdown.

When Danny Maimane turned 60 last year, he retired from his job at a Johannesburg bank. These days, he ferries neighborhood children to kindergarten, does handyman work at his Lutheran church and spends his mornings in the local library, reading.

“Danny has stopped working in the garden,” Gwen said, worry creasing her face. “I’m afraid to ask him why, but I think it’s because the price of flowers has gone so high.”

Gwen works at Soweto’s Baragwanath Hospital, the world’s largest, five times larger than Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center, as a nursing supervisor for a 40-bed AIDS ward. AIDS has ravaged South Africa, in part because of the government’s initial refusal to acknowledge the epidemic. Some of her patients are in their teens.

“You can see nothing is getting better,” she said.

As we ended our journey, I took stock. This was clearly a country with simmering day-to-day frustrations over what it sees as the slow pace of change, as well as the increase in violent crime, the AIDS epidemic, the gap between rich and poor, and the disheartening power struggle among its elected leaders.

Many of our friends were disappointed in their country. They hadn’t expected a miracle when Mandela’s ANC took over the government. But they expected more.

Still, I was struck by the speed and depth of South Africa’s transformation. I was reminded of that as I viewed the nation through my son’s eyes. It wasn’t so long ago, after all, that this was a nation ruled by a white minority that denied blacks the most basic civil rights. What Kevin saw was a vibrant, modern country where a growing black majority was clearly in charge, wielding real political and economic power.

Perhaps it was inevitable that, as an occasional visitor, I would see more change than they felt. Like the child whose growth we track on the bedroom wall, the citizens of a new democracy don’t always notice when they’re maturing. South Africa is coming of age, though. The marks on the wall don’t lie.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.