Analysis:: The Shakespearean excesses and political intrigues that drove Africa’s oldest strongman out of power

In a glitzy Johannesburg nightclub earlier this month, a wealthy young playboy poured an entire $660 bottle of Ace of Spades Armand de Brignac Champagne over his diamond-studded watch: It was Bellarmine Chatunga, the youngest son of President Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe.

He had bragged about the watch and chunky gold bracelet on an earlier social media post: “$60,000 on the wrist when your daddy run the whole country ya know!!!”

As Zimbabweans struggle to afford food, when many find themselves sleeping outside banks in the hope of withdrawing $10 in cash, the video drew outrage, even among the ruling elite that had propped up the 93-year-old Mugabe for 37 years.

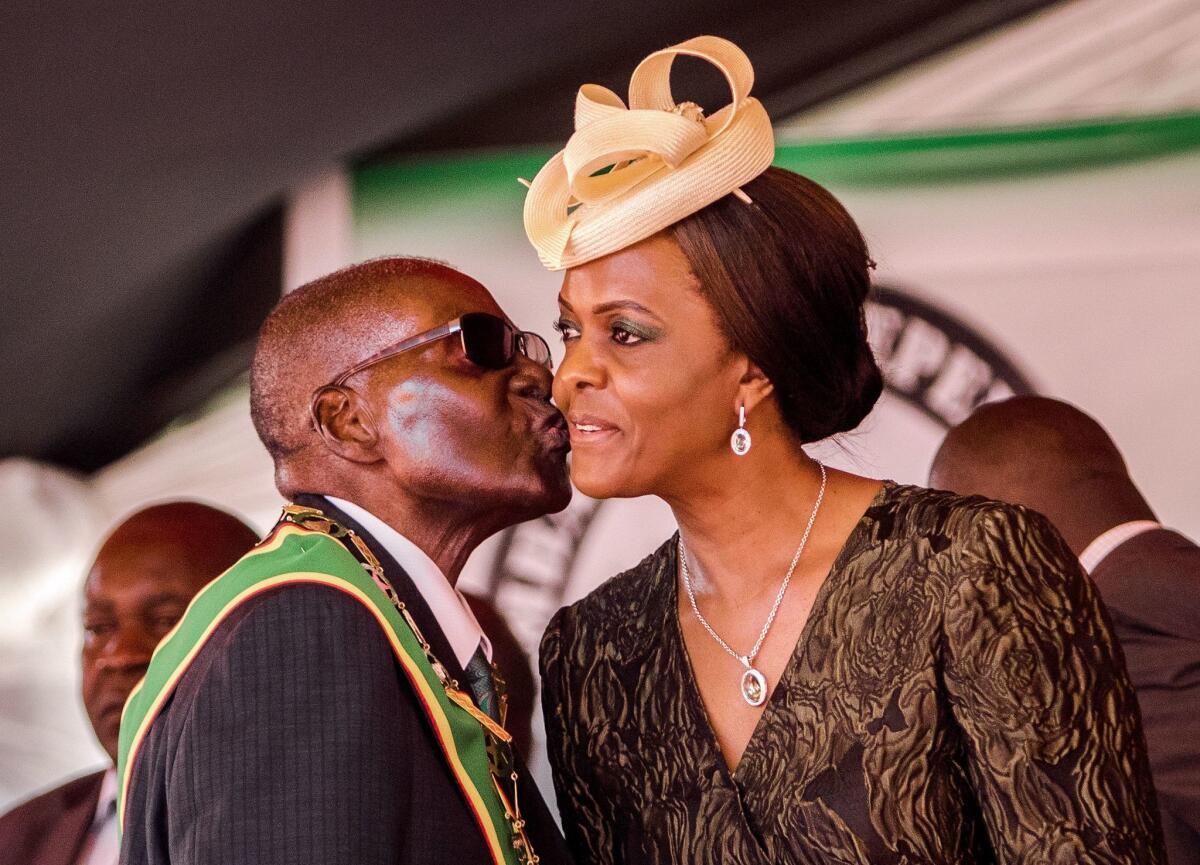

It hadn’t been an isolated incident. Mugabe’s wife, Grace, and her son from a previous marriage, Russell Goreraza, recently imported two Rolls-Royces, and she was caught up in a legal battle over a $1.35-million diamond ring.

Members of the ruling ZANU-PF party were furious that the first lady had seized majority control of a $1-billion government road contract. Then there was the incident involving a model who had been partying with her sons in South Africa: Grace Mugabe left an ugly gash when she hit her with a power cord and, facing charges of assault, she claimed diplomatic immunity and high-tailed it out of the country.

“It angered people. There have always been reports of the high living by these boys, high living by the mother, the father looking aside. They became arrogant and thought ‘No one can do anything to us,’ ” confided one ruling party figure, who wouldn’t be named for fear of reprisals. “There’s palpable anger in the military.”

The alarm over Grace Mugabe was magnified by her escalating power. When she attacked, government ministers fell. She said she could be president. “Give me the job and see if I fail!” she declared recently.

Zimbabwe’s fate came to a head this fall, according to numerous interviews with those close to the political intrigue, when Grace Mugabe turned her sights on former Vice President Emmerson Mnangagwa and his close allies among military commanders. At that point, sources say, those with any power to stop what was happening knew they would be finished — unless they toppled her. That meant removing Robert Mugabe.

Mugabe’s slow-motion downfall — planned for months by the military — is a story of his own hubris and arrogance, and his conviction that he was Africa’s last great liberation hero, with no living peers. For decades he chipped away at democracy and crafted the militaristic state that kept him in power, but he forgot that he was there at the military’s whim, not the other way around.

It was grand opera crossed with “The Sopranos,” full of scandal and treacherous turns, entertaining and dangerous. Accusations flew of poisoning, plotting, CIA espionage, military desertion and the theft of $15 billion in diamonds.

As the economy shriveled without foreign investment and a hard currency crisis sent prices of staples soaring 30% in a single week, many in the rank-and-file government felt hopeless at the prospect of going into elections in 2018 led by a president who could hardly stay awake in public meetings.

As Mugabe grew frail, he turned to promoting and protecting Grace, repeatedly warning the generals to stay out of politics, even as armed forces leaders were beginning to talk darkly of intervention.

The first hints of palace intrigue came last year, when higher education minister Jonathan Moyo — manipulative, arrogant, ambitious and a prolific tweeter with the handle @ProfJNMoyo— handed the first lady a report accusing armed forces chief Constantino Chiwenga, air force Cmdr. Perence Shiri and presidential guard Cmdr. Anselem Sanyatwe of plotting against Mugabe. In mid-2016, the president summoned the three men, who furiously denied the charges.

The accusation blew over, but it released its slow poison. Shiri retaliated on July 9, calling Moyo a liberation war deserter and collaborator.

Mugabe has spent his life cleverly playing one subordinate against another. But as his wife grew more ambitious, her poor judgment seemed to influence him. He embraced Moyo but lost the deft skill of juggling favor among sycophants.

He doled out benefits, handing out jobs and farms to loyalists but took many farms for his own family. When he turned against a minister or party official, he drummed up provincial branch party support to swiftly purge them.

In August, Mnangagwa fell seriously ill at a ZANU-PF rally eating ice cream from the massive Gushungo dairy farm owned by Grace Mugabe. He was airlifted to South Africa, where doctors found traces of poison.

“Why should I kill Mnangagwa?” Grace Mugabe insisted, furiously, last month. “Who is Mnangagwa on this earth? Killing someone who was given a job by my husband? That is nonsensical.”

At a Nov. 4 ZANU-PF rally in the southern city of Bulawayo, waiters handed out ice cream to all the VIPs — but pointedly excluded Mnangagwa and his wife. At the same event, ZANU-PF supporters heckled and booed Grace.

“Bring guns, soldiers and shoot me. I don’t care. I am the first lady, and I will stand for the truth. Yes!” Grace retorted. The jeers outraged the president, who blamed Mnangagwa. Three men later were charged with insulting the dignity of the president.

Mugabe chose his moment for Mnangagwa’s dismissal carefully — a day after the booing. Chiwenga had been sent to China on a weeklong mission. National army Chief of Staff Trust Mugoba was dispatched on a mission to the African Union in Ethiopia.

But the president failed to appreciate how a year of confrontation with the generals had destroyed his iron throne.

The growing crisis was not just political, but economic. Mugabe was isolated on the international stage; it was increasingly apparent that until the aging leader and his brood left office, Zimbabwe would be starved of investment and international support. Mnangagwa, in many eyes, was the only one who might be able to repair the situation.

“For us, we knew the trigger would be the day that he touched the vice president,” the ZANU-PF lawmaker said. “We could have had a coup in Zimbabwe some time back. It was only a matter of a trigger.”

Knowing he would be arrested, Mnangagwa immediately fled by road to Mozambique but was detained by police at the border at dawn. There was a tense standoff when a group of soldiers confronted police and took him under their protection. They sped away to a military airbase, where he was whisked out of the country.

Chiwenga knew that with his ally Mnangagwa narrowly escaping arrest, he likely faced the same fate. He considered flying back from China to Mozambique, but opted for confrontation. A group of military special forces, many in plain clothes, was at the airport when he arrived from China on Nov. 11, according to a ZANU-PF source. When police tried to arrest Chiwenga, they were overwhelmed.

On Monday, when Robert Mugabe received his weekly security briefings from the police, intelligence and military chiefs, Chiwenga sent a replacement. He spent the day meeting officers, before delivering a statement at military headquarters, warning that the military planned to take matters into its own hands. Flanked by 90 officers, Chiwenga delivered a message of stunning military unanimity.

As the cabinet met Tuesday, troops rolled into Harare from Inkomo Barracks outside the city. ZANU-PF issued a statement in the late evening accusing Chiwenga of treason, but it was a belated, hollow gesture. There was no way for police still loyal to Mugabe to arrest the head of the armed forces, with military forces already on the move.

The army seized control of state television, the police armory and other key facilities. The presidential guard led by Sanyatwe, whose job is to protect Mugabe, abandoned the president.

The deputy director of the Central Intelligence Organization, Albert Ngulube, had left Mugabe’s mansion in upscale Borrowdale neighborhood in the early hours of the morning when he came across vehicles moving toward the presidential residence and tried to stop them. The military beat him up, demanded his ID and arrested him, according to a ZANU-PF source.

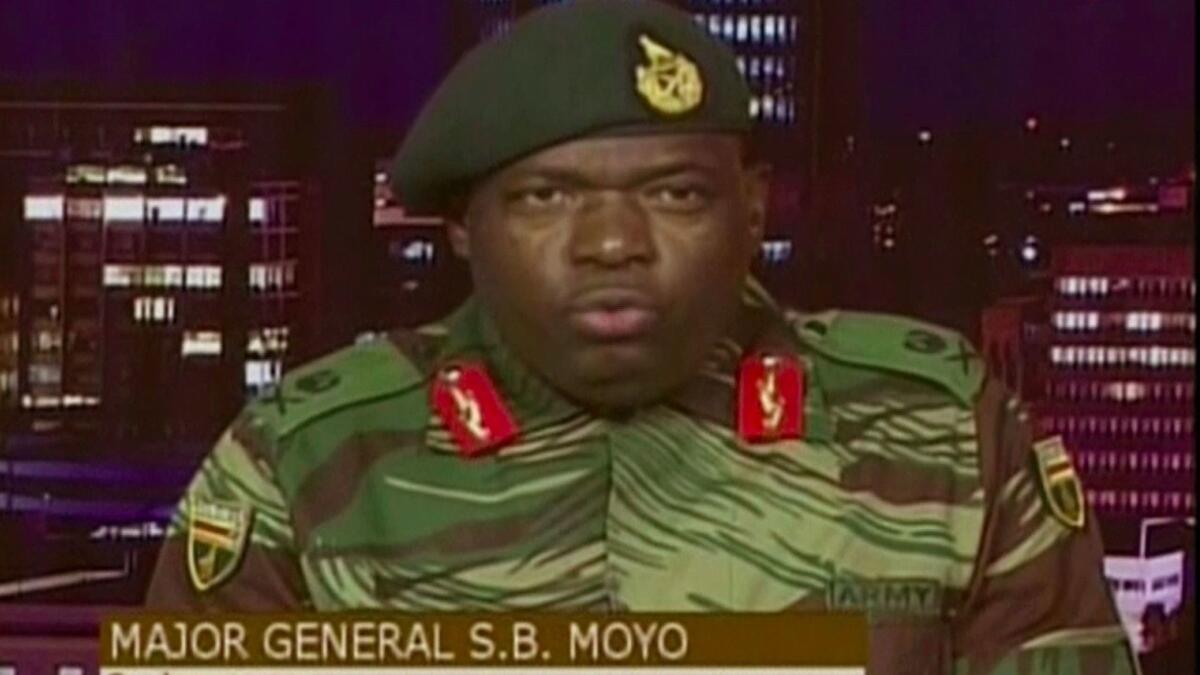

At 4 a.m., Maj. Gen. Sibusiso Moyo read a statement announcing that the military had taken over in order to arrest “criminals” around Mugabe and restore order.

The truth of what had happened hit home for many when state-owned television began playing a joyful song called “Pemberai,” or “Celebration,” by iconic Zimbabwean musician Thomas Mapfumo, a staunch Mugabe critic who had fled into exile in the U.S. in the 1990s because of state harassment.

The grudge between Jonathan Moyo and Chiwenga goes back more than four decades to the 1970s liberation war from white minority rule. Chiwenga has long accused Moyo of snitching on him for criticizing the liberation struggle leader at the time, Ndabaningi Sithole, who promptly ordered Chiwenga to be executed.

Mnangagwa’s camp also claims Moyo has been a CIA agent since high school. Moyo denies all these accusations, but he was among the first to be arrested by the military last week; he was being held in a cell underneath military headquarters, his future extremely bleak.

Grace Mugabe has been stripped of her power and denied access to the negotiations between Mugabe and the military over his exit. Her only path to safety on offer is for her husband to give up power, say sources familiar with the discussions. Otherwise, she stands not only to lose all her property, but also could face charges ranging from corruption and embezzlement to possibly even attempted murder, should authorities pursue the poisoning accusation.

Arrest and asset seizures also would potentially affect her children, particularly if she were convicted of fraud and a new government demanded the return of stolen assets in South Africa.

One of the ironies of the unfolding drama is the extent to which the army now confronting Mugabe has been one of the president’s chief weapons of terror over the years.

The military carried out massacres in Matabeleland in the 1980s on Robert Mugabe’s orders to eliminate opposition. Some 20,000 people were reportedly killed.

He forgot that ... he could be fired, like anyone.

— Tendai Biti, opposition representative

The army and war veterans evicted white farmers from their land soon after 2000 and got farms in return. Mugabe used the military to violently crush the opposition in successive elections and in Operation Murambatsvina in 2005, when up to a million people were displaced in opposition areas, their homes bulldozed.

Mugabe, say those who know him best, has always had an instinctive manipulative cunning and an acute understanding of how to wield force to break an opponent. When he saw a threat, he either crushed it or consumed it whole.

But as he aged, he grew more remote, stubborn and out of touch, and was loath to trust or consult his generals.

“He forgot the nature of the state that he himself helped to create, which is a militaristic, securocratic state,” said opposition figure Tendai Biti, a former finance minister. “He forgot that the militaristic state could just dump him when he stopped serving their interests. He could be fired, like anyone.”

Independent analyst Earnest Mudzengi said the closed, oppressive state Mugabe created likely will outlast him.

“He was made by the same guys who now want to do away with him. He made them, and he was made by them. Big people tend to overreach themselves,” he said.

“Basically what they [the generals] want is a return to the status quo,” he added. “People are celebrating, but it’s premature.”

Twitter: @RobynDixon_LAT

ALSO:

In Zimbabwe, Mugabe's fall appears to mark the end of Africa's postcolonial 'Big Men' era

Why a modest pastor with a flag is so threatening to Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.