Iran businesses await a post-sanctions bonanza

TEHRAN — The room at the Iranian Chamber of Commerce offices was packed and noisy. At the lectern, Deputy Foreign Minister Abbas Araqchi encouraged dozens of merchants and manufacturers to “seize the opportunity” that could result from an easing of international sanctions.

Businessmen who for years have been largely excluded from the global marketplace debated over ways to reach out to prospective investors.

“Why not send a delegation of businessmen to the U.S. Congress?” proposed Mahmoud Daneshmand, a veteran import-export man.

The deputy foreign minister, grasping the impracticality of that suggestion, responded in diplomat-speak: “Well, for the time being, the conditions are not right.”

Daneshmand is one of many Iranian entrepreneurs hoping that a political shift could yield a bonanza in commerce. Part of a once-flourishing mercantile class, he and his peers tend to avoid politics. But they’ve seen bottom lines plummet and businesses go bust as a result of sanctions linked to Iran’s nuclear program.

With the election last year of President Hassan Rouhani, a moderate keen to lure foreign capital, things are looking up for people like Daneshmand. They envision a nation restored to its pre-Islamic Revolution role as a strategically situated magnet for world trade, bolstered by the legions of Iranian expatriate businessmen in Istanbul, London, Los Angeles and elsewhere.

“The horizon is becoming brighter and brighter,” Daneshmand, 67, said in an interview at his office in downtown Tehran, around the corner from the chamber offices.

Nuclear talks resume next week in Vienna between Iran and six other countries: the United States, Russia, China, Britain, France and Germany. Negotiators hope to cement a permanent deal that builds on an interim accord hammered out in November in Geneva. Iran agreed to temporary nuclear constraints in exchange for limited sanctions relief.

The Obama administration, facing considerable domestic criticism of the deal, has sought to downplay the economic benefits for Tehran.

“We have made it crystal clear that Iran is not open for business,” Secretary of State John F. Kerry told a Senate panel this week in Washington. “They are accepting that. They are not cutting deals.”

There is no doubt that the sanctions have pummeled the Iranian economy. Prices have soared; employment is stagnant; and the national currency, the rial, has plunged in value by more than 50% in the last year.

Historically regarded as a nation of traders, Iran now is home to a battered and despondent business community.

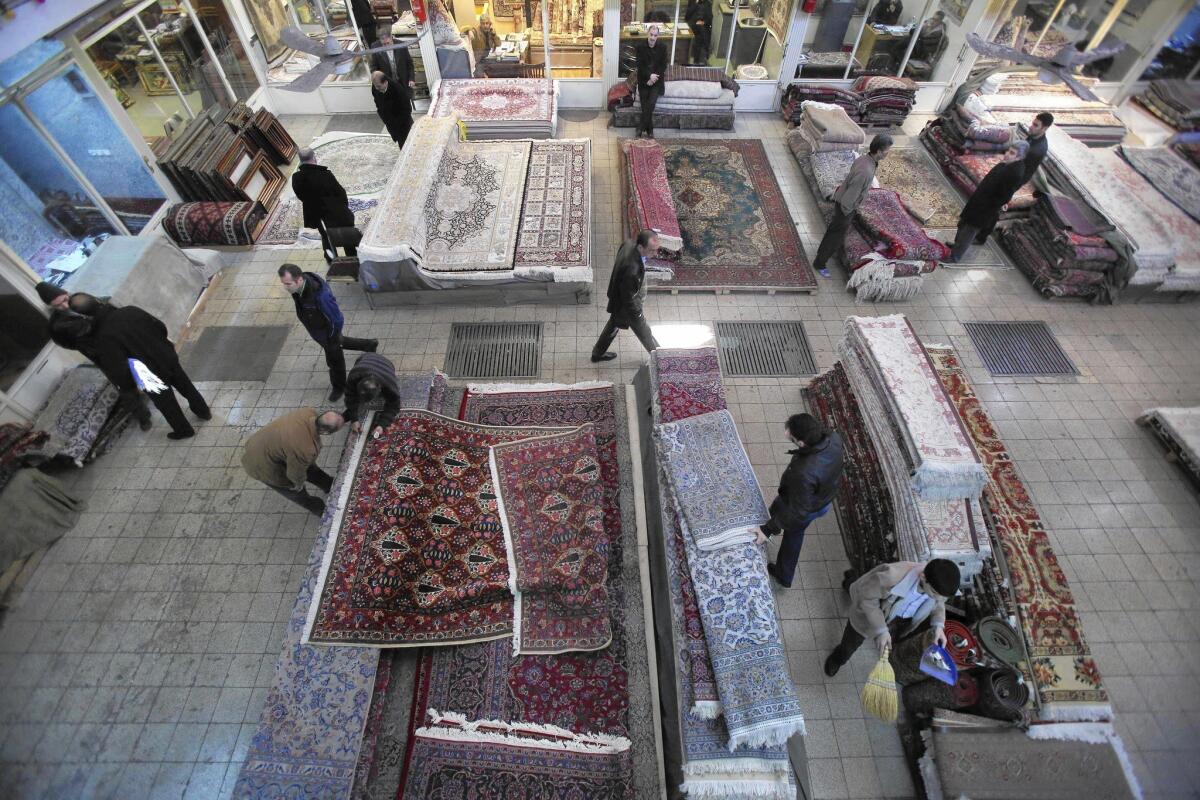

“People are losing their purchasing power,” said Mohammad Kurdestani, 60, owner of a carpet shop in Tehran’s grand bazaar. Like other merchants in the bazaar, he said sales were slow.

“I have a warehouse full of carpets, and then this shop,” Kurdestani said. “I have no option but to sell my carpets in my own lifetime, or end my business if I outlive my merchandise. Every year our business has been deteriorating.”

Rouhani took office in August, succeeding Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, whose confrontational style alienated many at home and abroad. He has focused on Iran’s economy and the effort to end sanctions.

In January, Rouhani attended the annual economic summit in Davos, Switzerland, where he reached out to the world’s entrepreneurial elite. He touted investment opportunities, met with European oil executives and emphasized Tehran’s desire to conclude a permanent nuclear accord that could result in a total lifting of sanctions.

Last month, Iran played host to scores of French executives in what was widely described as the most significant trade delegation to visit in more than a decade.

Daneshmand has exported petrochemical products and imported foodstuffs from Europe, Brazil and Argentina. But for two years, he said, his activities have been practically at a standstill because of sanctions.

Curbs on Iran’s access to the global banking system have paralyzed international commerce and proved especially damaging, he said.

“The export-import market has been ruined,” Daneshmand said from behind his desk. He wore a white shirt and red-and-black-striped tie, the latter a fashion accessory frowned on by Iran’s religious hierarchy as a relic of Western influence.

Still, the partial lifting of sanctions has made life a bit more satisfying for Iran’s global traders. “It is now much easier to rent vessels and insure them to carry foodstuffs, medicines and medical equipment to Iran,” he said.

One effect of the interim deal was to ease exports of medicines and medical equipment to Iran. But stiff banking limits remain in place.

“If only the banking sanctions were lifted, we could start buying raw materials and spare parts for the manufacturing of our soft drink,” said Jamshid Edalatian, 57, who owns a plant producing the Dynamo line of energy drinks.

Merchants and officials also hope for an influx of cash from sanctions relief. According to Iranian media reports, billions of dollars in unfrozen Iranian funds are stuck in Swiss banks waiting for clearance.

Yet the sanctions haven’t been a bust for everyone.

Those who specialize in circumventing the restrictions on items such as spare aircraft parts, medicines, food and computer components have thrived. Sanctions have reportedly been a major boon for Iran’s elite Revolutionary Guard Corps, which runs a multibillion-dollar business empire.

Araqchi, speaking to the Chamber of Commerce, slammed those making money off the country’s woes, though he didn’t single out anyone. “Our main problem here are those who are profiteering from the sanctions — economically and politically,” he said to hearty applause.

Revolutionary Guard leaders have mostly been mum about Rouhani’s economic strategy, focusing instead on disparaging the nuclear talks as a strategy aimed at toppling Iran’s leadership. The president’s policies appear to have the backing of Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

“It seems to me that the whole ruling establishment wants to get rid of the sanctions,” Daneshmand said. “If that is the case, then those who are profiteering from the sanctions will soon go out of business.”

While he awaits opportunities, the veteran globalist says, he will continue pitching his vision of market diplomacy. He foresees a regular interchange of corporate bigwigs and financiers, sipping tea and coffee and puffing on cigars in Tehran, New York and Los Angeles.

“Political delegations are always in a straitjacket,” Daneshmand said. “But if American business representatives can come here and talk with their Iranian counterparts, or we as private-sector delegations can go to the United States, then we can see the potential.”

Special correspondents Mostaghim and Sandels reported from Tehran and Beirut, respectively. Times staff writer McDonnell reported from Beirut.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.