Syrian war is slipping from the hands of battered rebels

ARSAL, Lebanon — The battle is not going well for rebels dug in across the nearby brown hills in Syria, where pro-government forces were closing in Saturday on the opposition stronghold of Yabroud.

Syrian insurgents and their many supporters on this side of the border exhibit both bravado and anguish about a battle, and a war, that is fast slipping from their hands.

“We have to keep on fighting to the last man, the last breath,” Abu Omar, 21, who lost his left leg to a tank shell outside Yabroud, said from his hospital bed. “We have no choice.”

Around him in this threadbare clinic, the bandaged and battered rebel fighters hooked to intravenous tubes testified to the plight of those aiming to topple the government of Bashar Assad.

[Update: 2:50 a.m. PDT: On Sunday, Syria’s official press agency reported that the Army had gained “full control” of Yabroud and that troops were “combing the city and eliminating explosives planted by terrorists.” Syrian officials routinely refer to anti-government rebels as terrorists. Among the opposition forces arrayed in Yabroud were fighters of the Al Qaeda-linked Nusrah Front, which the U.S. government has designated a terrorist organization.]

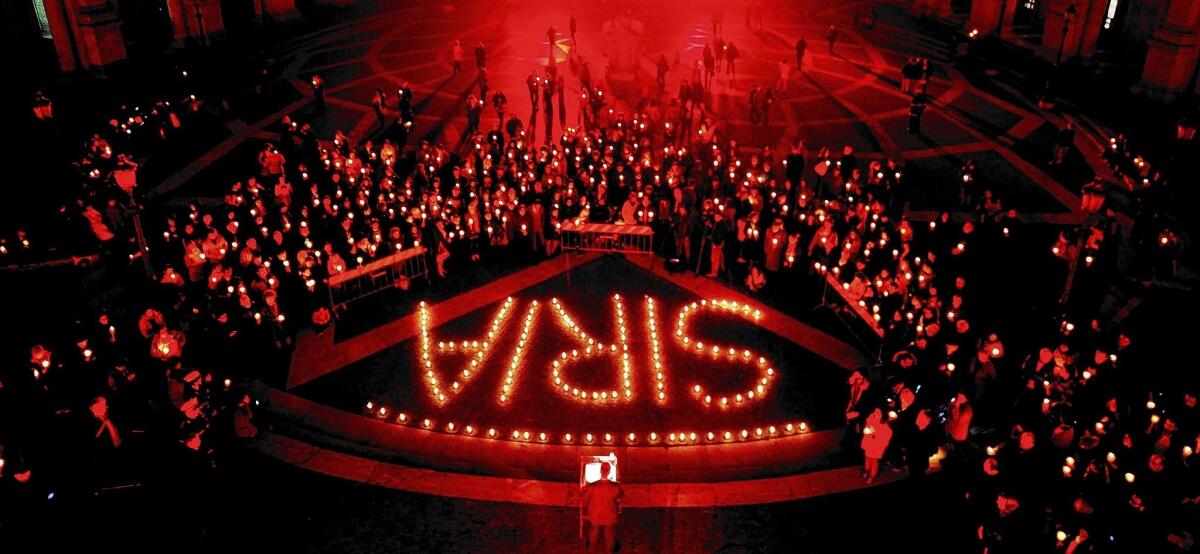

The Syrian war marked its third anniversary this week, a dismal milestone rendered bleaker still by the sense that bloodshed will not ease anytime soon.

The major diplomatic effort to end the war, the so-called Geneva process, appears near collapse.

“We have to be honest,” said Justin Forsyth, chief executive of Save the Children, one of many groups based in Lebanon that are working with war victims. “It’s getting worse and worse.”

Aid organizations on Saturday delivered their grim humanitarian toll from Beirut, the Lebanese capital: more than 100,000 dead; 2.5 million Syrians living as refugees, almost half of them children; 6.5 million forced from their homes inside Syria; hospitals and schools destroyed; entire towns and neighborhoods reduced to rubble.

With a sectarian makeup that somewhat mirrors the demographics of its war-ravaged neighbor, Lebanon has long been a secondary theater of the Syrian conflict.

A series of car bombs, gun battles, rocket strikes and other attacks here has been linked to the battle raging next door. More than 1 million refugees have relocated to Lebanon, taxing resources and inflaming social tensions.

While the government in Beirut is officially neutral in the Syrian war, many Lebanese have taken sides, often based on sectarian allegiance.

Here in Arsal, an overwhelmingly Sunni Muslim town in the northeast Bekaa Valley, residents openly sympathize with the mostly Sunni rebels fighting to oust Assad, a member of the Alawite sect, an offshoot of Shiite Islam.

A sleepy quarry town long known for distinctive white stone gouged out of nearby hills, Arsal has seen its population of 40,000 more than double with the influx of Syrian refugees. Their flight has accelerated with the government offensive in the adjacent Qalamoun region, which includes the rebel-held town of Yabroud, 35 miles southeast.

Syrian troops, backed by fighters from Lebanon’s Shiite Hezbollah militia, have been methodically taking back territory, hoping to seal off supply routes winding from Arsal to the embattled suburbs of Damascus, the Syrian capital.

A single mountain road connects Beirut to Arsal, now pocked with scattered settlements of blue and white canvas tents that house the Syrian refugees. Blooming cherry and almond blossoms provide a stark contrast to the town’s drab hues of brown and gray.

On the cluttered streets, a steady flow of motorbikes and vehicles with Syrian license plates ties up traffic. Lebanese authorities suspect that Arsal has become a hub for booby-trapped vehicles destined to be car bombs in Lebanon’s Shiite districts. Army checkpoints ring the city.

Yet Arsal is tranquil. No one brandishes weapons openly. Clusters of haggard young men linger about the town and the camps, awaiting their turn to return to battle, while ambulances arrive with the freshly wounded.

“We have patients coming all the time,” said Dr. Muhammad Ahmad, showing visitors around a clinic treating war wounded and refugees suffering from noncombat ailments.

A woman cried disconsolately. Her 2-day-old baby boy had died, the doctor explained. Physicians do the best they can, he said, but some equipment and medicines are lacking.

“This man needs a brain scan,” Ahmad said, pointing to an unconscious rebel fighter with tousled black hair and swollen eyes who apparently had suffered head trauma in a blast in Syria.

Ex-residents said life in rebel-held Yabroud was relatively normal until the Syrian military offensive began about a month ago, with aerial and artillery bombardments. The electricity was cut and running water ceased.

“I was in my house in Yabroud when a bomb exploded,” said a patient, Walid, 31, who, like others interviewed, did not want to give his full name for security reasons. He said he was a math teacher, not a fighter.

Shrapnel from the blast damaged Walid’s spine, and he cannot move his legs. He will need surgery. But with so many others suffering, Walid is hesitant to bemoan his fate.

Still, he mourns for his hometown.

“There is no more Yabroud,” Walid said. “It is a cursed town.”

Special correspondent Nabih Bulos contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.