Muslims in U.S. forces must weigh faith, duty

By noon, Ensign Ahmed Aslam has made his way to the Tarawa Terrace Chapel, transformed for an hour every Friday into a mosque. He removes his pressed camouflage shirt, hangs it on a metal folding chair, and places his shiny black combat boots beneath a table in the back of the room.

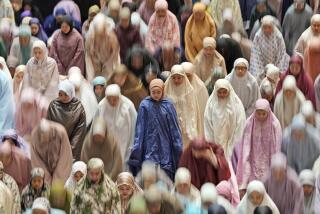

Aslam kneels alongside a half-dozen other men on the linoleum floor covered with Persian-like throw rugs and camouflage print mats. Facing Mecca, Aslam closes his eyes, lifts his cupped hands to his face and prays to Allah.

It is a ritual he performs five times a day, whether in a prayer room on the base or aboard a U.S. warship.

Aslam is an officer in the U.S. Navy and a Muslim. Like many practicing Muslims in the military, he has found himself in a precarious situation as the United States engages in a war against an enemy that has unleashed terrorism on Americans in the name of Islam.

A native of Pakistan who is a naturalized U.S. citizen, Aslam, 35, has practiced Islam since he was a child. Like many Americans, he has done a lot of soul-searching since the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. He has studied the Koran, the holy book of Islam, for answers and found peace in its message: Terrorism has no place in Islam. For him, there is no internal conflict in going to war against the Muslim nation of Afghanistan.

“It is simple. A Muslim looks at what is right and wrong and fights against injustice. What the terrorists did was wrong,” said Aslam, a health-care administrator in the 2nd Medical Battalion at Camp Lejeune, a Marine Corps base about 40 miles north of Wilmington, N.C.

“Of course, innocent people dying anywhere is a concern, and everyone hopes it can be avoided,” he said. “Unfortunately with war, this kind of stuff tends to happen.”

For some, the decision has been more difficult. It took a lot of prayers and reading of the Koran for Pfc. Omar Jammeh, a native of the heavily Muslim country of Gambia, to accept the role he might have to play in the war.

“In some ways, it’s like fighting your own brother. We are all one family,” said Jammeh, 28, who is not a U.S. citizen. “But we have to remember that we are fighting terrorism, not Muslims. Muslims must fight for peace and justice against those who have used oppression against others.”

To address concerns of Muslims who were uncomfortable with deployment to Afghanistan, a panel of scholars in the Middle East recently issued a fatwa, or religious opinion, denouncing the Sept. 11 hijacking attacks on the United States, saying it is the duty of Muslims to participate in the mission to apprehend the terrorists.

Fatwa draws controversy

But the fatwa, requested by Army Capt. Abdul-Rasheed Muhammad, who became the military’s first Muslim chaplain in 1993, has been controversial within the armed forces.

“We want to make it clear that this is not an Army document,” said Lt. Col. Ryan Yantis, an Army spokesman at the Pentagon. “It supports the basic tenets of what we are doing in Operation Enduring Freedom and basic Army values, but it is not a binding document. When there are questions, we encourage the service people to refer to the chaplains.”

Just as many Muslim military personnel have had to find a comfortable balance between religion and duty, so has the armed forces. An institution accustomed to rigid rules and conformity, the U.S. military has wrestled with how to accommodate the religious needs of its diverse ranks without compromising its mission.

Most bases have a prayer room. The armed services offer combat rations that comply with Islamic dietary restrictions and troops can get Fridays off for prayer as long as they make up the time.

Still, the transition has been slow and often bumpy, Muslim activists said, because new policies have been designed mostly to accommodate other religious groups.

For Muslims, modesty is an issue. The fewer than 600 Muslim women in the military are not allowed to wear hijabs, the scarves commonly worn by Muslim women in the U.S. and Middle East. Muslim men and women also complain about the uniforms, particularly body-hugging pants worn during physical training exercises.

“In most cases the military does its best to accommodate religion, but the policies affecting Muslims are antiquated,” said Qaseem Uqdah, a retired Marine Corps gunnery sergeant who is director of the Virginia-based American Muslim Armed Forces and Veterans Affairs Council. “And enforcement is generally left in the hands of commanders, some of whom have not caught up with the times.”

Some 4,000 Muslims serve in the military, according to the Department of Defense. Uqdah’s group, however, estimates the number at 15,000, explaining that many recruits do not identify themselves as Muslims on enlistment papers for fear they will be ostracized. The overwhelming majority of Muslims in the military are African-American.

“The greatest misconception is that when you say Islam, it has an automatic connotation of terrorism and hatred of other races. It’s that kind of stereotyping the military is trying to work on,” Uqdah said. To accommodate the growing numbers of Muslims, the Pentagon has increased efforts to add Muslim chaplains and educate military personnel about the religion, according to Maj. James Cassella, a spokesman for the Department of Defense. There are 14 Muslim chaplains--eight in the Army, three in the Air Force and three in the Navy, which has two serving the Marine Corps.

“Our efforts predate Sept. 11, but at a time like this there is an added interest. We take time out every month to look at the issues and make sure people understand the applicable policies regarding respect for fellow servicemen and what their religions might be,” Cassella said.

The military encourages men and women in uniform to follow the chain of command, and when there is a dispute, they are unlikely to go over the head of their commander or file a complaint with the inspector general. Chaplains, including non-Muslims, are trained to intervene and are available as a resource.

`Not like civilian life’

“It’s not like civilian life where people would report non-accommodation, because the ramifications can be pretty severe if it’s not done right,” said Ingrid Mattson, a professor of Islamic studies and director of the Hartford Seminary that trains Islamic chaplains.

“You don’t want to be charged with insubordination or have people develop a bad attitude toward you,” she said. “The chaplains are aware of that and they know to ask if everything is OK.”

At Camp Lejeune, where there is no Muslim chaplain, Master Sgt. Rick Foster, 43, is the Islamic lay leader. As the spiritual adviser to Marines and sailors, he has spent a lot of time since the terrorist attacks counseling and explaining Islam to others. Like them, he sometimes struggles too.

“My struggle is what to do if it gets to the point where these false accusations in America regarding Islam deprive me of my duties as a senior staff member in the Marines. What side am I going to fall on? Personally, I say I am going to fall on the side of Islam, but the struggle is what is right and wrong. A lot of people in the military deal with that,” said Foster, a 20-year Marine veteran and an African-American.

“For us, Islam is not just a religion, it is a way of life. I am Muslim first. Second, I am a Marine,” he said. “In Islam, we are taught to honor contracts, and I made a contract with the Marine Corps. When I am out on the battlefield, I am going to do what I know I’ve got to do. What the terrorists did is wrong. And in that sense, when I go to bed at night, I’m at peace.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.