In Crimea, Russians demand that Ukrainian troops swear allegiance

BAKHCHISARAI, Ukraine -- The tense military standoff in Crimea continued Monday as Ukraine’s army and naval forces were blockaded by invading Russian troops and supporters, at some sites demanding that the Ukrainian units surrender their bases and swear allegiance to the Kremlin and Russia’s armed forces.

The demand represented an alarming sign that the fresh Russian forces had come here to stay, some analysts said.

“The fact that Russians openly demand that Ukrainian officers and soldiers in the Crimea take an military oath to Russia may mean one thing: The Kremlin intends to keep them here for a long time, if not for good,” said Kost Bondarenko, head of the Ukrainian Policy Institute, a think tank based in the Ukrainian capital of Kiev.

“It means that Ukraine is steadily losing the Crimea to Russia and it will be extremely difficult to get it back as the Ukrainian army is incapable of opposing Russia,” he said. “So Ukraine is in a painstaking round of negotiations on all levels to stop Russia’s expansion into the Crimea.”

In Bakhchisarai, the ancient capital of Tatar rulers, armed Russian commandos without insignia on their uniforms arrived in Russian military trucks Sunday and took up positions surrounding a Ukrainian army base in the center of the city, about 25 miles west of Simferopol, the capital of Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula.

On Monday morning, the Russian forces issued demands.

“In the talks that I conducted with them early in the morning, they proposed that the officers and soldiers of the unit should take a Russian military oath,” Col. Sergei Stashenko, commander of the Ukrainian forces at the base, said in an interview with The Times. “Needless to say, this is absurd and totally unacceptable to us as we remain committed to the oath we took before our country and the Ukrainian people.”

He said the Russian officers then suggested that the Ukrainians leave their weapons in storage rooms, surrender the base to Russian forces and go home. Stashenko said he also rejected that proposal.

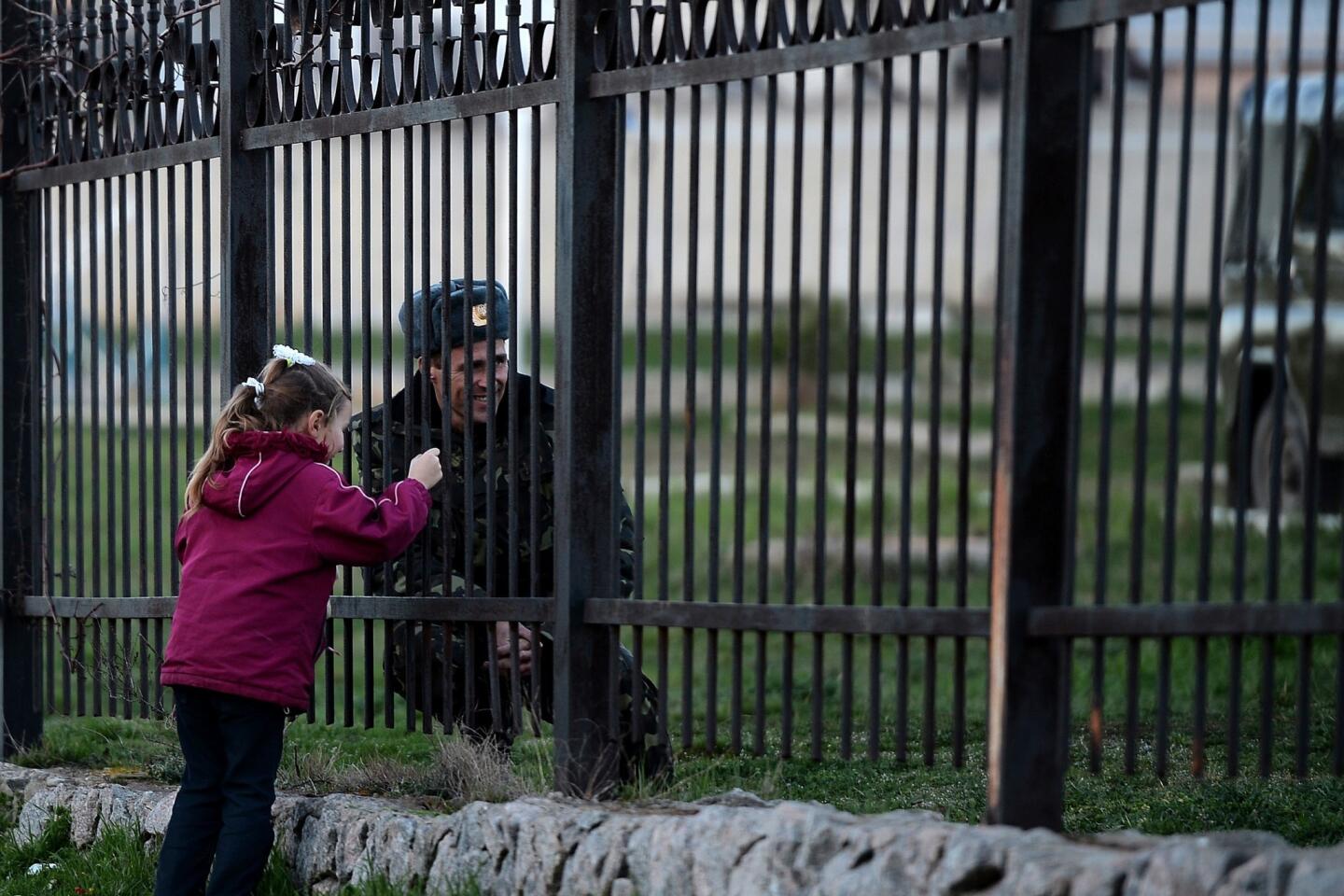

In the meantime, Russian soldiers were sitting outside and walking in twos and threes around the perimeter of the base on a sunny afternoon, petting stray dogs and joking with a couple of local young women in a nearby park, but with their firearms on the ready.

Over the barbed wire atop an iron fence around their base, armed Ukrainian soldiers could be seen watching the movements of the Russians through binoculars.

“I don’t know what plans they follow and what orders they have, but they must know that should they attempt to storm the base, we will fight back until the last drop of our blood,” Stashenko said. “Whatever they are up to, we will not allow them to get hold of our weapons.”

“We don’t need their weapons,” said a young Russian soldier who refused to give his name and rank. “I am not going to fight with my brothers and shoot at them. I have many relatives and friends in Ukraine. We are here only to prevent the bases’ weapons from getting into the hands of fascists and extremists.”

The Russian soldier did not specify who those “fascists” and “extremists” were, but Russian President Vladimir Putin has used much the same language to describe the former Ukrainian opposition politicians and protesters who drove pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovich from power late last month, charging that members of the Russian-speaking majority in Crimea are in danger from Ukraine’s new leaders.

It’s the justification Russian officials have cited for last week sending additional military forces to Crimea, where Russia has long leased naval facilities from Ukraine.

Another Ukrainian unit, Coastal Defense Brigade No. 36 based in the town of Perevalnaya, by Monday had been under Russian siege for more than three days. Its commander, Col. Valery Boiko, is confronting a significantly superior force of Russian troops that have parked their military vehicles about 100 yards from his base and set up tents.

Some of the Russian troops -- in new green uniforms with no insignia but sporting elbow and knee pads and vests -- were sitting on the grass, basking in the sun. Others were standing along the road with firearms or slowly walking around as if patrolling the area. Most wore woolen black or green masks.

“[The Russians] demand that we betray our oath of allegiance and surrender our weapons to them, but that will not be as long as I command this unit,” Boiko said in an interview with The Times. “We have plenty of weapons, ammunition and armored vehicles at the base but we don’t intend to let this arsenal fall into strange hands. If they try to take them away from us by force, we will fight.”

“However, I don’t think that either we or they need that war,” he added, shaking his head.

A pro-Russian local activist making his way toward the base through a cordon of Russian-speaking Crimean militiamen said they were trying to prevent a bloodshed between the Russian and Ukrainian soldiers should the latter try to break the blockade.

“We are not concerned with which country these soldiers represent,” said the activist, Andrei Skrynnik, pointing at Russian soldiers standing close. “We see that they pose no danger to us, as they are trying to help us to prevent the base’s weapons from getting into the wrong hands.”

Close to the gates of the base stood a small group of women who work at the Ukrainian base or have relatives there. They were tense, nervous and agitated.

“What Russia is doing here is extremely ugly,” said Svetlana Gorbacheva, a 50-year-old librarian for the unit and a mother-in-law of one of its officers. “We are extremely scared that some lunatic may make the first shot and the whole situation will deteriorate into a bloodshed, if not a real war between our fraternal peoples.”

The first shot had already been fired Monday morning by a Ukrainian soldier guarding a military air base in Belbeck near Sevastopol, the home of the Russia’s Black Sea Fleet.

The soldier shot in the air when a group of Russian servicemen threw several stun grenades toward Ukrainian officers and soldiers protecting the base. After that, the Russians retreated to their positions around the base. During the incident, a Ukrainian officer became the first casualty of the overall confrontation; he was taken to hospital with a light injury caused by one of the stun grenades, said Vladislav Seleznev, a spokesman for the Ukrainian Defense Ministry.

“So far this conflict claimed no deaths and the confrontation without use of arms is mostly concentrated around our military bases in the Crimea blocked by Russian forces,” Seleznev said in an interview with The Times. “Right now, the fighting is mostly limited to an information war, where Russians are using dishonest and unfair arguments. No one is encroaching upon the lives of Russian nationals in the Crimea and no one is threatening the lives of Russian navy personnel stationed here.”

On Monday morning, Denis Berezovsky, the former Ukrainian naval commander fired Sunday from his position for “high treason,” appeared at the gates of the country’s naval headquarters in Sevastopol, surrounded by a group of Russian nationalist militiamen.

Berezovsky is the highest-ranking military defector in Ukraine, publicly pledging allegiance Saturday to Crimea’s newly declared pro-Russian regional government.

Berezovsky wanted to persuade other Ukrainian officers to follow his defection but was sternly rebuffed, Seleznev said. High-ranking navy officers who gathered in the courtyard of the base responded by singing a Ukrainian national anthem.

Also on Monday, Ukrainian Deputy Interior Minister Mykola Velychkovych charged that Russian forces planned to kill several Ukrainian soldiers in Crimea on Monday night to provide a pretext for the Russian military incursion.

“You are thus provoking a bloodshed, which is not happening in the Crimea,” Velychkovych appealed to the Russian leadership in televised remarks. “We are calling upon you to stop! Bear in mind that the situation is being monitored.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.