Brennan Likes Playing for Big Stakes : He Builds Success With His Imagination, Other People’s Money

The initial in Robert E. Brennan’s name stands for Emmet. But maybe it should be changed to Everything. Many Marylanders would say that it stands for Evil.

Since Brennan bought his first horse in March of 1980, the 41-year-old Wall Street wunderkind hasn’t just entered racing, he’s turned the game topsy-turvy.

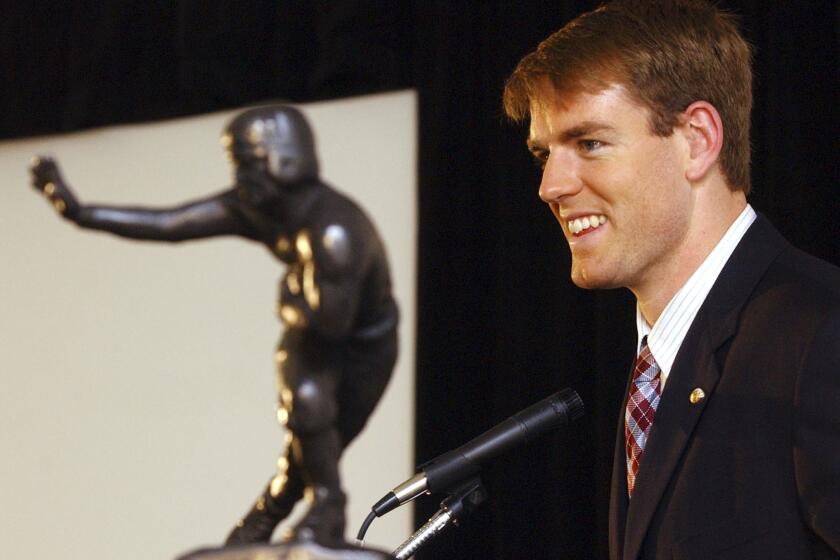

Buying horses at million-dollar prices. Rebuilding a race track that burned down. Buying a race track that was already there. Trying to buy still a third race track and making overtures to take over New York’s hard-pressed off-track betting system. Offering purses to horsemen as though he were dealing in Monopoly money and then, two weeks ago, the coup of coups: Brennan, waving $1 million of bonus money in each hand and smiling his choir-boy smile, lured Spend a Buck, the winner of the Kentucky Derby, away from the Preakness, the second race in the Triple Crown series, and got him to run Monday at Garden State Park in the Jersey Derby, which was a $1-million race even without the bonus.

“This will be the most exciting day of racing in the history of New Jersey,” Brennan says of the Jersey Derby. If it is, it’s not because of the quality of the field--mostly leftovers from the Triple Crown wars--but because of what Spend a Buck can accomplish. In about two minutes, the time it will roughly take to run 1 miles, the 3-year-old colt may earn $2.6 million, by far the largest single payday in the history of racing, easily topping the $1,350,400 that Slew o’ Gold collected for his win and $1-million bonus in last fall’s Jockey Club Gold Cup at Belmont Park.

Of the $2.6 million, the race’s $600,000 winning purse will come out of Brennan’s pocket and the $2-million bonus would be paid by a Texas insurance company. A company, by the way, that might have a few actuarial openings after Monday, because Brennan has paid only $75,000 for the premium.

That’s the Brennan style, taking the grandiose route with somebody else’s money. He bought Garden State Park, the 287-acre Cherry Hill track that burned to the ground from a kitchen fire in April of 1977, for $15.5 million, only $1 million of which was cash. The balance--and the additional $160 million or so it cost to rebuild--has mainly come from 66,000 shareholders in International Thoroughbred Breeders, Brennan’s New Jersey-based company that previously consisted of only a bloodstock operation and horse insurance business.

In February of ‘84, about 14 months after the Garden State purchase, Brennan announced that ITB had bought Keystone, another race track in the Philadelphia area, for $37.5 million.

Since then, Brennan has been thwarted in an attempt to buy Monmouth Park, a track on the New Jersey shore not far from New York. Monmouth was sold instead to the state-run New Jersey Sports and Exposition Authority, an agency Brennan is not comfortable with because it also runs the Meadowlands track and receives financial concessions not available to private track operators.

Brennan planned to sue over the Monmouth sale but dropped litigation when Atlantic City Race Course received permission by the state to run a 34-day season each summer at Garden State.

“I’m still sorry that we don’t have Monmouth under our umbrella,” Brennan said, “but in the long run what we wound up with will be better for our stockholders. It could mean $100 million to them over the next 10 years.”

That’s if business gets better at Garden State. The first night of the first season at the self-styled “Race Track of the 21st Century” was marked by a turnout of 27,000 fans--with Brennan flying himself in via helicopter from his Wall Street offices and signing autographs as he made his way through the crowd--but attendance and betting have not been bullish since then. An average crowd runs about 11,500 and bets in the neighborhood of $1.2 million, a per-capita wager of $104. The national per capita last year was about $147.

Brennan, who started First Jersey Securities, one of the country’s leading brokerages with reported sales of $3 billion last year, on $300,000 in borrowed money in the late 1960s, is not discouraged by the Garden State figures.

“We’ve built the track with the best bricks and mortar and we treat the purses (16 races worth $100,000 or more) as a capital expense,” he said during an interview in his New York office, which has a 14th-floor view of the Hudson River. “You start with mediocrity and you find that you never dig yourself out of mediocrity. Lee Iacocca wouldn’t start out by building junk cars and asking people to buy them so he could accumulate enough money to build better cars.

“We hope to develop new racing fans the way the Meadowlands did. And it took the Meadowlands six months before it hit a $100 per capita. We’re over that in less than two months.”

Garden State, which will hold a harness meeting the last four months of this year, is seven levels of red brick, white cement and green glass. There are glass-enclosed elevators, an atrium for a paddock, a polished-mirror ceiling in the grandstand, a $500,000 terrazzo floor in the clubhouse and red, black and white marble bathrooms in the Phoenix, a gourmet-dining restaurant that seats about 1,000 people.

Despite a heavy speaking schedule, addressing groups interested in his business philosophy, Brennan and his wife Patricia, who have seven children ranging in age from 13 to 21, are frequent front-row diners in the Phoenix.

“I have an enormous energy level,” Brennan says. “The speaking engagements help. They give me a way of recharging my own batteries.”

Brennan comes from a family of nine children. He grew up in Newark, N.J., had a newspaper route, worked as an office boy in the advertising department of the Newark Evening News, bet horses through bookies and skipped school to take the trolley and the subway to Aqueduct, where he’d have to sneak in because the track didn’t allow kids.

He studied under monks at St. Benedict’s Prep in Newark and got an accounting degree from Seton Hall University. It is said that the 6-1 Brennan’s blond, blue-eyed, boyish appearance makes him look like an ex-altar boy.

When he was 23, his 21-year-old brother was murdered during a robbery attempt in their parents’ front yard. The night of the funeral, Agnes Brennan, their mother, collapsed and died. “She was 53,” Bob Brennan said, “and they said it was from a broken heart.”

Henry Brennan, who became a widower, had sold insurance, but he began working for his son Bob. “After about a year,” Bob Brennan said, “he began asking for Fridays off and started going away on weekends. The family thought he had a girlfriend and was trying to figure out a way to tell us. But he was going to religious retreats. He was ordained (as a priest) at age 65 and served as a chaplain in a hospital in Milwaukee until his death last summer.

“He was one of my great heroes. I think that things that happen in the past, even though they’ve already occurred, can shape things positively or negatively for the future, depending on how you choose to use them.”

Lately, Brennan has become unpopular in Baltimore, where Pimlico lost the Kentucky Derby winner when Spend a Buck’s owners chose to run in Monday’s Jersey Derby. Pimlico General Manager Chick Lang, who’s worked at the track for 25 years, had a grandfather who trained a Kentucky Derby winner (Judge Himes in 1903) and a father who rode one (Reigh Count in ‘28), knew racing tradition before he knew Gerber’s and reacted furiously when he learned Spend a Buck wouldn’t be running in the Preakness.

Lang has accused Brennan of making a pre-Jersey Derby deal with Dennis and Linda Diaz, owners of Spend a Buck, to buy an interest in the colt. The Diazes and Brennan say they have no deal--Brennan concedes that he’s still interested in the horse--but Lang goes on, saying: “Anyone who believes that Brennan hasn’t purchased part of that horse must still believe in Santa Claus.”

Before the Preakness, Brennan believes he was set up by a Baltimore radio station that asked him to come on and discuss the Spend a Buck situation.

“When I got on, they had already been ripping me for about 20 minutes,” Brennan said, “and it wasn’t explained to me that Lang would also be on.”

With Brennan listening from his end, Lang said: “All I know is that I drive a Ford, cut my own lawn and carry my lunch in a brown paper bag.”

To which Brennan replied: “I used to do all those things, too. But I had a dream and my stockholders had a dream. Now we don’t have to.”

Lang wound up calling Brennan a “snake-oil salesman” before the program ended. Since then, after being told by friends how he sawed himself off, Lang has regretted saying that, but he still gives Brennan little credit: “It was a million-to-one shot (getting a situation in which Spend a Buck would win two Garden State races and the Kentucky Derby in order to make himself eligible for the $2 million) and Brennan got lucky. He had to have that horse for the Jersey Derby. Otherwise, what would he tell his stockholders, what with the track doing such bad business?”

Brennan thinks that some traditions can be dangerous things. “If we went by tradition,” he said, “Jackie Robinson would never have gotten the chance to play baseball. Sonny Werblin would never have given Joe Namath $400,000 to play football. Women wouldn’t be voting. They wouldn’t be playing football on Monday nights. Is doubling the prices to get into the Kentucky Derby (as Churchill Downs did this year) tradition? It’s money, it’s not tradition.”

Brennan points out that the first Jersey Derby was run in 1864, nine years before the first Preakness. “If I really wanted to attack the Preakness,” Brennan said, “I could have run the Jersey Derby the same day.”

Besides Pimlico, Brennan has sent warnings in the direction of New York by scheduling some of Garden State’s top stakes in direct conflict with races at Belmont Park.

“New York doesn’t have a claim to being the No. 1 state by birthright,” Brennan said. “Whether it’s securities or racing, this is still a free-enterprise system. One of the great things about this country is that leadership can be challenged and that competition is healthy.”

According to Brennan, Belmont has threatened to penalize trainers who send New York horses to Garden State by squeezing them on stall space. Gerry McKeon, president of Belmont Park, responded to Brennan’s comment about a birthright by saying: “He’s absolutely right. We are No. 1 because we’ve earned it. We’ve got a purse distribution of $75 million, which is tops in the country. Garden State is putting all their eggs in one basket, luring one big horse for one big purse.”

Brennan, who owns horse farms in Kentucky, Florida and New Jersey and lives in Brielle, N.J., a 14-minute helicopter ride from his New York office, was, despite his adversary position, recently asked to speak to a group of New York thoroughbred breeders in Albany.

“This is no time for New York to become protectionist,” Brennan said. “Rather, it’s the time to dream great dreams again.”

Afterward, New York Gov. Mario Cuomo said: “I didn’t know whether to cheer, buy stock or join a crusade.”

Brennan is used to pressure. He got it for 11 years from the Security and Exchange Commission, which brought charges of price manipulation against First Jersey. The charges were dropped in November of last year.

“The SEC is used to strangling little people,” Brennan said. “Sometimes I’m right and sometimes I’m wrong, but in this case I was right and the SEC was wrong to intimidate me. They wanted me to plead nolo contendere, like Spiro Agnew had done, and I told them, ‘Baloney!’ In the beginning it was David versus Goliath, but by the time we got to the end, we were both giants. I tried to use it as a positive experience, one that helped me grow emotionally and spiritually.”

In July of last year, Forbes magazine ran a cover story on Brennan entitled “The Golden Boy,” in which it characterized the First Jersey operation as “fobbing off shoddy and overpriced merchandise on a not very well informed public.”

Brennan gave The Times a copy of an eight-page letter that he sent to Forbes, rebutting the story. The magazine didn’t print any of the letter.

Turning to a stack of papers behind his desk, Brennan produced a color brochure advertising First Jersey. The front was a reprint of his picture on the Forbes cover.

“At least they took a good picture of me,” Brennan said.

In New Jersey, where the sport has been threatened by Atlantic City casinos, racegoers will frame that picture. They’ll use it for dart practice in Maryland.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.